North Carolina's production of naval stores-tar, pitch, and turpentine, all products of the pine tree-began in the 1720s and declined as a major industry by the Civil War. The abundance of pine trees in North Carolina and England's dependence on seagoing vessels made naval stores an essential commodity in the colony's economy. Great Britain even offered a bounty for naval stores, encouraging the growth of the industry. With a multitude of longleaf pines, the Cape Fear Valley, especially the region made up of present-day Harnett and Cumberland Counties, was the location of most naval stores production. Settlers in this region extracted sap from pine trees, collecting it in barrels. These barrels were placed on flatboats made of logs and transported down the Cape Fear River to Wilmington. By 1768 North Carolina accounted for 60 percent of the naval stores produced in the colonies.

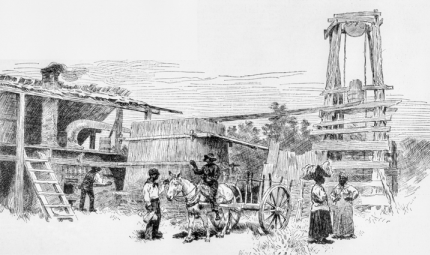

The nineteenth century saw further expansion in the industry, with a resurgence beginning in the 1830s and continuing through the 1850s. In 1840 North Carolina produced 95.9 percent of all naval stores in the United States. In 1847 De Bow's Review reported that the state produced 800,000 barrels of turpentine, with an estimated market value of $1.7 to $2 million. The industry employed almost 5,000 laborers and had 150 processing stills. By the late 1850s naval stores became the South's third-largest export crop. This growth was further spurred by the completion of the Wilmington & Weldon Railroad in 1840 and the North Carolina Railroad, running from Goldsboro to Charlotte, in 1856, which extended transportation routes into the interior of the pine forest regions.

Because naval stores production was labor intensive, the labor of enslaved people was used to ensure its profitability. Enslaved people and their labor was used especially in the winter months, and conditions tended to be much harsher than in plantation agriculture because of the solitary and migratory nature of the work. On occasion, enslaved people resisted their harsh treatment and exploitation by running away or by setting fires in the forest so that turpentine could not be collected.

After the Civil War, the naval stores industry declined in North Carolina. This decline is attributed to several factors: the burning of some large pine forests by Union general William T. Sherman's troops decreased the amount of turpentine produced for a time; iron vessels eventually replaced wooden sailing ships, causing a reduction in demand for the industry's products; and, finally, synthetic solvents began to be used to thin paints, diminishing the need for turpentine.

The phrase "Tar Heel," the nickname for North Carolinians and the state itself, possibly originated from the fact that people working around turpentine stills often got tar on the soles of their shoes, allegedly helping them "stick" to their assigned jobs.