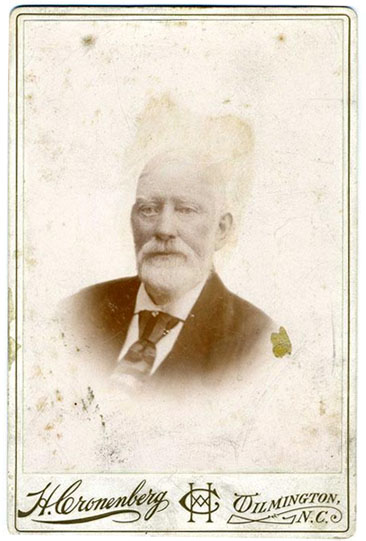

17 Apr. 1823–5 Nov. 1894

James Reilly, soldier, was born at Athlone, County Roscommon, Ireland, the son of James and Anne Brady Reilly. At age sixteen he ran away from home and enlisted in the British army, having dreamed of being a soldier from his early boyhood. Though his mother soon secured his discharge, he joined the army again when he reached eighteen. Discontented with the service and his ill treatment, he deserted and fled to America. He lived at first with his uncle in New York, but, returning to his childhood desire to be a soldier, enlisted in the U.S. Army in New York in 1845 and was assigned to the Second Artillery Regiment. Reilly served throughout the Mexican War as a private, was wounded at Churubusco, and then was injured when his horse was shot from under him at Molino del Rey. Discharged with a surgeon's certificate of disability for the injury in 1848, he recovered sufficiently to enlist again in the Second Artillery less than two months later. Over the next few years, he rose to the rank of first sergeant of his company, serving in Virginia, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, and Indian Territory. He wrote of his experiences in the army in the early 1850s in reminiscences published over fifty years later, after his death.

In 1857 Reilly was promoted to ordnance sergeant, a rank set aside for a few dozen noncommissioned officers who had distinguished themselves by their faithful service. Initially assigned to Fort Myers, Fla., he was transferred to Fort Johnston near the mouth of the Cape Fear River in about 1859. Ordnance Sergeant Reilly had full responsibility for the fort and the weapons and ammunition stored in its magazine since no regular army troops were stationed there. On 9 Jan. 1861 a number of local citizens of Smithville (present-day Southport) banded together and forced Reilly at Fort Johnston and Ordnance Sergeant Frederick Dardingkiller at Fort Caswell on nearby Oak Island to open their magazines and surrender their ordnance stores. Soon realizing that they did not have much popular support for their actions, the citizens returned what they had taken to the two ordnance sergeants and a crisis was averted.

When the Civil War broke out in April, Colonel John Lucas Cantwell headed a force of North Carolina troops that compelled Reilly to surrender Fort Johnston. Reilly chose to resign his warrant as an ordnance sergeant and was subsequently discharged by order of the adjutant general. His decision to join the Confederate cause clearly resulted from his having passed nearly all of his army service in the slave states. Initially he served as a drillmaster under Major William H. Whiting, but in May 1861 the North Carolina governor granted him a commission as a first lieutenant and assigned him to the First North Carolina Artillery (Tenth North Carolina Regiment). Because of his long experience in the regular army, he was advanced to the rank of captain just a month later and assumed command of the Rowan Artillery, which came to be known as Reilly's Battery. Throughout most of his more than two years' service with the battery, it was a part of General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia.

Reilly commanded his battery with remarkable competence and reliability. Since he was unusually attentive to the maintenance of his equipment and the condition of his horses, the inspector general consistently rated his battery to be among the best in the army. The battery was also noteworthy for its performance on the battlefield. Reilly's men took part in each of the Army of Northern Virginia's major engagements from the Seven Days' Battle to Gettysburg with the exception of Chancellorsville, when the battery was temporarily in North Carolina. At various times, Generals Whiting, D. H. Hill, J. E. Johnston, and E. M. Law observed that they would rather have Reilly's Battery than any other in the Confederate army.

By mid-1863 Reilly was discouraged and angered because many less experienced artillery officers had been promoted to the rank of major. Merit had produced his commission in 1861, but the Irish-born soldier found that merit was secondary to politics and personal favoritism in his further advancement. In August 1863 he submitted his resignation, but it was not accepted. Still, his letter produced the desired effect. Governor Zebulon Vance promoted Reilly to major of North Carolina Troops in September, and, soon afterwards, President Jefferson Davis also raised him to that rank. Reilly accepted Vance's promotion and declined Davis's, thus paving the way for his return to North Carolina. In the spring of 1864 he reported to General Whiting, commander of the Department of North Carolina, and was placed in charge of an artillery battalion assigned to the Cape Fear defenses. Reilly helped to repulse the Union attack on Fort Fisher in December 1864. Fort Fisher was again attacked in January 1865 and when both its commander, Colonel William Lamb, and General Whiting were wounded, the command passed to Major Reilly. When Union forces overwhelmed the defenders, Reilly surrendered his sword to Captain E. L. Moore of Massachusetts and was taken prisoner. Nearly three decades later Moore would return the sword to him. Reilly was confined at Fort Delaware until released after taking the oath of allegiance four months after his capture.

After the war Reilly resided in Wilmington and worked as superintendent of the Wilmington and Brunswick ferry company. He spent his last years farming in Columbus County.

Reilly married Irish-born Anne Quinn in Brooklyn in 1848 shortly after he was granted a disability discharge and before he began his second term of enlistment. After her death in 1872, he married Martha E. Henry in about 1876. At the time of his death, he was survived by four children by his first wife and two by his second.