22 Mar. 1824–10 Mar. 1865

William Henry Chase Whiting, Confederate general and defender of Wilmington, a descendant of prominent seventeenth-century English settlers in Massachusetts, was born in Biloxi, Miss., the son of Levi, an officer in the regular army, and Mary A. Whiting, both natives of Massachusetts. Intellectually gifted, he was graduated at the head of his class from the Boston Public School, Georgetown College (1840) where he completed the four-year course in two, and West Point where he was top man in the class of 1845. It is said that his academic record at the U.S. Military Academy was not surpassed until the graduation of Douglas MacArthur in 1903.

![Image of William Henry Chase Whiting, from Internet Archive 1901, [p. opposite title page], published in 1901 by Raleigh, E.M. Uzzell, printer. Presented on Internet Archive.](/sites/default/files/cu31924092908544_0007_Whiting_Wiliam_Henry_Chase_IA.jpg)

Like most of the best graduates of West Point, Whiting was assigned to the engineers and as a result missed active duty in the Mexican War. Most of his antebellum career was spent at work on river and harbor improvements and fortifications on the Gulf, California, and South Atlantic coasts. In the latter assignment he was lighthouse engineer for the two Carolinas. Among other projects between 1856 and 1858 he reopened communications between Albemarle Sound and the Atlantic Ocean. During a two-year tour on the lower Cape Fear River in North Carolina, he married, on 22 Apr. 1857, Katherine Davis Walker, the daughter of John and Eliza Morehead Walker of Wilmington and Smithville, who survived him, childless.

Promoted to captain in 1858, Whiting spent the last few years before the Civil War in Georgia and Florida. Apparently he was the senior U.S. officer present at Savannah when state authorities took over that city's military posts in January 1861. Despite his Northern antecedents and a mother, brother, and two sisters in New York, Whiting unhesitatingly sided with the South during the secession crisis, and he resigned his commission on 20 Feb. 1861. Soon afterwards he joined General G. P. T. Beauregard as a staff engineer at Charleston. Following a brief appointment as inspector general of North Carolina in April, he was commissioned chief of staff to General Joseph E. Johnston in Virginia. Johnston praised highly his services in the destruction of the Harpers Ferry arsenal and in the rapid transfer of his Army of the Shenandoah from western Virginia to Manassas, as a result of which he was promoted to brigadier general on the field of First Manassas on 21 July 1861. The next year Whiting commanded a division with conspicuous ability in the heavy fighting of the Peninsula, Seven Pines, Valley, and Seven Days' campaigns. His services as both staff officer and combat commander were commended by Beauregard, Johnston, and T.J. Jackson, the last an officer not lavish with his praise.

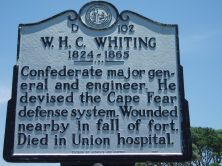

In November 1862 Whiting became commander of the military district of the Cape Fear with headquarters at Wilmington, and six months later he was promoted to major general. To him belongs much of the credit for the skillful innovations in construction and artillery placement that developed Fort Fisher into one of the strongest defense works in the world. As the defender of Wilmington, Whiting seems to have enjoyed public esteem in North Carolina, although he was criticized by D. H. Hill for lack of cooperation with operations outside his immediate sphere. For his part, Whiting repeatedly requested transfer to a more active front, an application that was granted in May 1864 at the special request of General Beauregard.

Beauregard, who was defending Petersburg with a small force while the main armies were still north of the James River, planned an ambitious offensive against the Federals at Bermuda Hundred on the Peninsula. Traveling rapidly to Petersburg by rail, Whiting was assigned a small scratch division and an important role in a plan that required him to cover Petersburg while conducting part of a complicated offensive. In the ensuing action of Port Walthill Junction, he failed to get his force into action and carry out his mission. A rumor circulating at the time that he was debilitated by drink or drugs seems to have been unfounded, and it is more likely that his deficiency was the result of prolonged loss of sleep. He was not disciplined in any manner but was returned to duty at Wilmington by his own request.

Whiting's forces repulsed a major Federal advance on Fort Fisher at Christmas 1864, but when the attacking expedition returned the next month he was superseded, on orders from Richmond, by Braxton Bragg. Discovering that Bragg intended to evacuate Wilmington without using the reinforcements that had been sent there and thus to sacrifice Fort Fisher, Whiting entered the fort during one of the heaviest naval bombardments in history. Perhaps remembering the recent blot on his reputation, he apparently determined to share the fate of the outnumbered garrison and outgunned fort with which he had been so long connected. He declined to take over the command from Colonel William Lamb but serving as a volunteer took a notable part in the hand-to-hand fighting during the last assault on the fort. While leading a countercharge on 15 Jan. 1865, Whiting was shot twice in the leg. Taken prisoner with the survivors of the garrison, he was sent to Fort Columbus (now Fort Jay) on Governors Island, New York harbor, where he wrote an official report maintaining that Fort Fisher could have been held if Bragg had committed the reinforcements on hand, an opinion shared by other officers present and by North Carolina public opinion. Although his wounds were not thought to be fatal, Whiting declined from depression and the hardships of his midwinter transport and confinement; he died within eight weeks, shortly before his forty-first birthday. After well-attended services at Trinity Episcopal Church, New York City, he was buried in Greenwood Cemetery, Brooklyn. In 1900 his remains were reinterred in Oakdale Cemetery, Wilmington.

Whiting was described as soldierly in appearance and of below average height. A wartime likeness that has been widely published seems to portray a slender, intelligent, sensitive face. An adopted North Carolinian, he was one of not a few Northerners who gave the last full measure of devotion to the Southern Confederacy. Whiting undoubtedly possessed superior ability but lacked the opportunity and perhaps the stolidity of character required of the most successful military commanders.