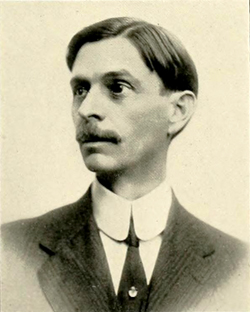

29 Dec. 1867–16 Oct. 1940

William Preston Few, the first dean (1902–10) and the fifth president (1910–24) of Trinity College, was the first president of Duke University (1924–40). His English ancestor, Richard Few, was in Pennsylvania in 1682; his great-great-grandfather, William Few, Sr., left Maryland to settle in Orange County, N.C., near Hillsborough. William's son, James, became involved in the Regulator movement and, though not a principal leader, was captured by the forces of Governor William Tryon and hanged on 17 May 1771 after the Battle of Alamance. James left infant twins, William and Sarah. William moved to upper Greenville County, S.C., at an early age, married Sarah Ferguson, and became the father of sixteen children, one of whom was Benjamin Franklin Few (1830–1923). Benjamin, who graduated from the South Carolina Medical College and served as an assistant surgeon in the Confederate Army, married Rachel Kendrick (1840–1922), a cousin, in 1863; they had two girls and three boys. After the war, he returned to Greenville County and settled in a rural community called Sandy Flat, where William Preston Few was born.

"Willie" was, he said later, "an invalid boy." Thus he received his early education from his mother and did not attend school regularly until he was about thirteen. He was baptized into the Methodist church on 27 Sept. 1871, and religion never ceased to be a formative influence in his life. Few finished high school in Greer, S.C., then attended Wofford College in nearby Spartanburg where he was graduated in 1889. Despite some illness he had an excellent record in a course of study that included physics, trigonometry, Latin, Greek, and Old English. In addition, he was one of the founders of The Journal, the Wofford literary monthly, as well as a member of the Chi Phi social fraternity and the Preston Literary Society. He also learned to play tennis.

Few's teaching career began at St. John's Academy in Darlington, S.C. The next year he was invited to teach in the Wofford College preparatory school. Two years later he entered the graduate school of Harvard University where he received the master of arts (1893) and doctor of philosophy (1896) degrees—both in modern languages. At Harvard, as at Wofford and St. John's, he was plagued by ill health; he later wrote that "until about 1924 I had bad health all my life." He welcomed the opportunity to return to a softer climate when he received an invitation from President John C. Kilgo, whom he had known in South Carolina, to teach for one year at Trinity College. Recently the college had been moved from Randolph County, N.C., to Durham, a rising city of the New South with a population of about 8,000. Few's appointment became permanent when at the end of the year Kilgo reported to the trustees that both the college and the town recognized him "as a man of superior ability." Few, who took an active part in college affairs, soon was "Manager of Athletics" as well as professor of English. In 1902 he became the first dean of Trinity, "invested with all the authority of the President in his absence."

A significant event early in Few's deanship was the so-called Bassett affair. John Spencer Bassett was a member of the faculty and editor of the South Atlantic Quarterly, recently established at Trinity. In an article appearing in the magazine he discussed the growing antipathy toward African-Americans, deplored recent restrictive legislation, predicted that blacks would continue to struggle toward equality, and referred to Booker T. Washington, the African-American leader and educator, as "the greatest man, save General Lee, born in the South in a hundred years." The press of the state raised an intemperate outcry. The issue was academic freedom and whether the trustees would sacrifice Bassett to those who were making him an excuse to get at Kilgo, the Dukes, and Trinity—all somehow related to such odious things as the Tobacco Trust, the Republican party, and a trend in education opposed to native institutions. The upshot was that when the trustees met in December 1903 Kilgo presented them with an eloquent plea in behalf of free speech. The trustees declined Bassett's proffered resignation and brought in a report asserting the principle of academic freedom. This report had been prepared in advance by Dean Few with the assistance of William Garrott Brown, a journalist and intimate friend of Few, who happened to be visiting him at the time. The episode put Trinity in a good light in the view of educators and foundations, and it illustrates Few's willingness to take a firm stand while avoiding an open confrontation.

Kilgo resigned as president of Trinity after he was elected bishop in the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, and on 6 June 1910 Few was chosen to succeed him as of 1 July. There is no doubt that Benjamin N. Duke and Kilgo were the prime movers in the appointment. The student newspaper acclaimed Few's election, as it had his deanship, and the elaborate inauguration ceremony on 9 Nov. 1910 was attended by distinguished educators. In his well-received address, the new president indicated that he would continue on the path marked by his predecessor, and that the greatness of the college would depend not on size but on "the quality of the men who teach and the quality of the men who learn."

On 17 Aug. 1911, in Martinsville, Va., President Few married Mary Reamey Thomas in a ceremony performed by Bishop Kilgo. Miss Thomas was a graduate of Trinity and a former pupil of Few; by chance they had renewed their acquaintance in 1908 on the ship Few took to Scotland for a summer in the Shakespeare country and in France. The couple had five sons: William, Lynne Starling, Kendrick Sheffield, Randolph Reamey, and Yancy Preston. A devoted family man, Few considered the loss of Preston at age sixteen a great tragedy.

From the beginning Few had cast his lot with Trinity. Though inclined to keep a low profile as far as political pronouncements and public issues were concerned, he worked quietly and persistently to raise the standard of excellence in education while continuing to teach and even tutor some students privately. For nearly ten years (1909–19) he was coeditor of the South Atlantic Quarterly and a frequent contributor. He also was a member of the committee of the Board of Overseers, which visited Harvard's Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in 1911. In 1913 he was president of the North Carolina Literary and Historical Association, and in 1918 he became a trustee of the Jeanes fund, also known as the Negro Rural School Fund, which was supported by the Anna T. Jeanes Foundation. Since 1897 he had been a delegate to many meetings of the Southern Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools, and in 1932 he was elected its president.

Benjamin N. Duke, who had favored Few's election as president, continued to support him, and there developed a bond of affection between the two men. Other friends of Few who were associated with the Dukes, especially Clinton W. Toms, a Trinity trustee, were encouraged to keep the needs of Trinity before James B. Duke; undoubtedly the latter's appraisal of Few was a factor in Trinity's future. Although the Dukes made frequent and generous gifts to Trinity, Few was anxious to enlist their financial support on a more permanent basis. In 1916 James B. Duke "spoke definitely," in Few's words, "concerning his purpose to give away during his lifetime a large part of his fortune." However, World War I intervened and it was not until February 1919 that Few proposed to Duke a plan for the creation of a Duke Foundation to be interlinked with Trinity through a self-perpetuating board. Duke, Few suggested, could become a member of the executive committee of the college (Benjamin N. Duke had been a trustee since 1889, and his son Angier B., a graduate of Trinity, since 1913), could "manage the property" of the foundation, and could "determine the allotments to be made each year." James B. Duke became a trustee of Trinity College in 1918, attended the commencement of 1919, and seemed to Few "happier than I have seen him in a long time." Soon Few wrote Benjamin N. Duke, "I am sure that we are now on the eve of developments beyond our dreams."

Early in 1921 Few began to work on a plan for the establishment in Durham of a hospital and clinical medical school as a joint enterprise of Trinity, The University of North Carolina, and possibly Wake Forest and Davidson colleges. Few enlisted significant support, some from outside foundations and some from James B. Duke, but skeptics influenced public opinion against the project, and in the end Few's plan failed. Few, who had foreseen this possibility, later wrote that the undertaking "served two good purposes—it kept the road open for a first-rate School of Medicine later on, and it put Mr. James B. Duke on his mettle."

Discussions between Few and Duke continued until a plan of organization took shape in 1921. The idea of a university, rather than Trinity alone, emerged; Few "suggested that the new institution be called Duke University." In the spring of 1924 James B. Duke authorized the purchase of land near the campus. This was not easy, and it came to seem, wrote Few, "as if we had a difficult task before us." On an afternoon walk Few "accidently rediscovered a beautiful woodland tract to the west of the campus." More than 5,796 acres of this land was acquired, some in small parcels, without any public knowledge of the identity of the purchaser. Then it was learned that a local stone, near Hillsborough, was "easily available, durable, beautiful, and in every way fitted for our building requirements."

In December 1924 James B. Duke established the Duke Endowment, which provided financial assistance for educational institutions, hospitals, and agencies of the Methodist church in the two Carolinas. Twenty percent of the income from the initial endowment of $40 million was to be accumulated until an additional $40 million was available. By his will Duke provided further support for the Duke Medical School, hospital, and other purposes, eventually giving the university a total of some $19 million apart from the annual income from the endowment. The fact is, however, that this was not enough to do all that Duke had envisioned, and some hard priority decisions had to be made. One of the problems Few never mastered was how to keep the public from being misinformed by the press on this apparently endless wealth.

James B. Duke died in 1925 and thus did not play a further direct part in the metamorphosis of a small college, with professional training restricted to law and engineering, into a university equipped with a hospital, medical school, divinity school, college of engineering, school of forestry, graduate school, and a coordinate women's college. If there were those who thought Few not equal to the task of working successfully with this complex problem, they soon found that he had a toughness, a resilience, a shrewdness, and a latent capacity to be firm and resolute. But his tendency was to be cooperative and conciliatory and to expect tolerance and reason to prevail. Long before his death the university had taken much the form he had envisioned. That he was for progress and futuristic is seen in his attitude toward academic freedom, the education of women, and the unification of the Methodist church, as well as in his lively distrust of the demagogue.

Few was a modest man, even to the point of shyness at times, but he had a quiet charm especially noticed in small gatherings. Although he had to do a good deal of public speaking, he was never a platform orator. The words of a longtime friend give an accurate summation: "He was as kind and tenderhearted as a woman. But to imagine him without will or backbone would be to err grossly." He died at Duke Hospital and was buried in the crypt of Duke Chapel.