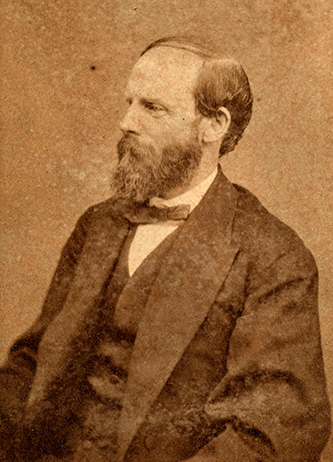

6 Jan. 1821–1 Apr. 1907

Calvin Josiah Cowles, merchant, real estate and mine operator, union leader, and assayer, was born in Hamptonville, the son of Connecticut natives Deborah Sanford and Josiah Cowles. In describing his family's settlement in North Carolina, Cowles noted that his father, after spending a winter or two in the South, went home to Connecticut, married Deborah Sanford in 1815, "hitched up to some little peddling wagons taking a limited supply of furniture and came through to Hamptonville, Surry County, where they settled and went to work." Josiah Cowles was a tinsmith who became a prosperous merchant and active Whig, serving as chairman of the Surry County court and as a member of Governor William A. Graham's council of state (1846–49). Deborah Cowles died in 1827, leaving three children: Calvin; Abel Sanford, who was educated as a physician and died young; and Eliza Ann, who married Dr. Bilson B. Benham. In 1828, Cowles, Sr., married Mrs. Nancy Carson Duvall, who also had three children: Robert Carson, an 1841 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy; Alvan Simpson, Jr.; and Martha Temperance.

Cowles's formal education was limited to the schools of Hamptonville, supplemented by a lifelong habit of home study, business travel, and wide-ranging personal associations. After an apprenticeship in his father's store in Hamptonville and marriage to his stepsister Martha Duvall, on 19 Sept. 1844, he set up in trade as J. and C. J. Cowles in Elkville near the Caldwell/Wilkes county line.

For thirteen years, 1846 to 1858, Cowles built a trade with the mountain people in furs and hides, dried fruits, wool, feathers, and wax, items that he sold to merchants in New York, Baltimore, Boston, and Philadelphia; there, on annual trips lasting several weeks, he purchased paint, books, guns, medicines, salt, ear trumpets, and dulcimer strings. By 1849 he had expanded his business to collecting roots and herbs; it was called a "risky business" by his father, but Calvin, charmed by the perfumes of his roots and herbs and listing their names like a litany—balm of Gilead, lady slipper, lobelia, ginseng, mayapple—surmounted the hazard of getting them to market, over the mountains in wagons to railroads and rivers for shipment out of Wilmington and Charleston, S.C., at exorbitant freight rates. In three years, shipping his bales of sage to butchers, ginger to the beer makers, and sassafras root to the Shakers in Lebanon, N.H., and New Lebanon, Ohio, he could claim to have the largest root and herb business south of the Potomac.

While at Elkville, Cowles became infected with mining fever and began buying land on speculation, paying twenty-five cents to a dollar an acre, often buying at foreclosure sales or purchasing land warrants, sometimes from men who had served in the militia during the Cherokee Removal of 1838. He read textbooks on mining; corresponded with miners in Virginia and Tennessee; sent letters to the governor to be forwarded to peripatetic Ebenezer Emmons, the state geologist; sought investors; and sent minerals and Indian artifacts to the Crystal Palace at the New York World's Fair of 1853, to promote the western counties of North Carolina.

In 1858 he gave up his store and the postmastership he had held since 1852 and moved his wife and four sons to Wilkesboro, where he opened another store and continued to buy mineral lands. Although he was interested in many mines—Baker's in Caldwell County, Elk Knob in Watauga, Flint Knob in Wilkes, Martin's in Yadkin—Cowles's favorite was the Gap Creek Mine near Jefferson, Ashe County, which for forty years he tried to develop into a great copper mine.

On the eve of the Civil War, Cowles estimated that he owned 6,000 acres in Wilkes and adjoining counties, 1,100 in Kansas, and 400 in Missouri, in addition to three farms at Gap Creek (400 acres), one near Elkville called the Buck Dula lands (357 acres), and 200 acres at Wilkesboro.

Cowles was active in Whig politics in the antebellum period. As a determined Unionist, he opposed secession; by June 1861 he noted, "War sets upon me like a nightmare . . . with all enterprises falling to the ground." He continued as postmaster in Wilkesboro under the Confederacy, but his repeated refusals to take the loyalty oath finally resulted in removal of the post office from his store in 1863. In Hamptonville his postmaster father was in a similar political position, although after two years of Confederate rule, Cowles, Sr., signed the loyalty oath, believing by 1863 that the new government was stable.

During the war, Cowles channeled his trade to the markets in Charleston, New Orleans, and Mobile and began selling his roots and herbs to the Confederate medical purveyors in Charlotte and Goldsboro. He was exempt from military service because of a chronically infected leg, but three half brothers served the Confederacy: Miles Melmoth, a lawyer who died of wounds in Richmond in July 1862; William Henry Harrison, cavalry officer, lawyer, and U.S. representative (1885–93); and Andrew Carson, state legislator (1860–73). His stepbrother Robert Carson Duvall (1819–63) commanded the North Carolina naval steamer Beaufort at Oregon Inlet in July 1861.

By May 1865, Wilkesboro was cut off from the world without mail service and with most of the horses too worn out to travel. Cowles borrowed fifteen dollars to get to Charlotte to ship his roots, ruefully commenting that his coat was threadbare, yet he was considered a rich man. After several years of intermittent illness, his wife died on 3 Apr. 1866, leaving five sons: Arthur Duvall (1846–1902), merchant; Calvin Duvall (1849–1937), career army officer; Josiah Duvall (1853–80), surveyor; Andrew Duvall (1856–99), lawyer and adjutant general; and William Duvall (1862–1912), bank clerk.

During Reconstruction, Cowles became an active Republican. He was elected by the General Assembly to serve on the council of state for Provisional Governor William W. Holden (May–December 1865). In his bids for elective office, Cowles was defeated as a delegate to the constitutional convention of 1865, defeated by one vote for the state senate, and elected a delegate from Wilkes County to the 1868 constitutional convention, by a majority of 1,600 votes. He was chosen to preside at the convention, held 14 Jan.–17 Mar. in Raleigh. When the convention disbanded, he remained in Raleigh to see the constitution through its printing and then personally delivered a parchment copy to President Andrew Johnson.

On 23 July 1868, Cowles and Ida Holden, daughter of the governor, were married in the governor's private residence by the rector of Christ Church.

In the months and years directly after the constitutional convention, Cowles unsuccessfully sought the Republican nomination for Congress from his district; became Wilkes County's representative on the board of trustees of The University of North Carolina; and was appointed a director of the Eastern Division of the Western North Carolina Railroad Company and treasurer of the Wilmington, Charlotte, and Rutherfordton Railroad Company. In May 1869 he took an oath of allegiance to the federal government and became a pension agent for Union veterans or their survivors in Wilkes County. He was also a delegate to the National Immigration Convention in Indianapolis in 1870. When Governor Holden's impeachment trial was held in the senate chambers of the capitol in Raleigh, Cowles attended his father-in-law much of the time during the months of the trial, from January to March 1871. Like Holden, Cowles saw the trial as a struggle between an elected governor and a powerful, secretive Ku Klux Klan.

Cowles solicited the superintendency of the U.S. Branch Mint in Charlotte from a number of political friends, hoping that through the assay office, the only activity at the mint revived after the war, he could promote mining interests and establish contacts with men in the mineral business. Receiving the appointment in January 1869, he closed his house and store in Wilkesboro and moved his family into the living quarters at the mint. From then until he resigned in 1885, he battled to restore the South's only remaining branch mint to a permanent center for coinage. He wrote innumerable letters to the officials at the U.S. Mint and the Treasury Department, to North Carolina's congressmen, and to newspaper editors, arguing that the gold miners of North Carolina, Tennessee, and Georgia needed not only the assay office at Charlotte but the services of a full-scale mint.

After his return to Wilkesboro in 1885, Cowles set up an office and worked full-time on his land interests. His sons assisted him actively, looking up land grants, surveying tracts, raising money, and appearing in court to argue claims. He rented many acres as farm lands and worked to promote mining and railroad development in the area.

At this time he rediscovered a number of his earlier interests, one of which was service as a voluntary county statistician and weather observer for federal and state agricultural departments. In addition to his reports on county crops and physical conditions, he sent specimens for identification to the divisions of entomology, ornithology, botany, mammalology, and seeds at the U.S. Department of Agriculture. He nourished a long-time interest in family history and began to compile information with a view to publication. The work was completed by his son, Calvin D., who published a two-volume genealogy of the Cowles family in America in 1929.

Two of Cowles's children acquired more than local fame: Calvin Duvall (1839–1937), West Point graduate, fought Indians in the West and the Spanish in Cuba and compiled the atlas accompanying The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies ; Charles Holden (1875–1957) was active in state Republican politics, served several terms in the state legislature, was U.S. congressman in 1908–10, and was editor-publisher of the Wilkes Patriot. Other children by Cowles's second marriage were Annie Laurie Holden, who married Hamilton V. Horton; Nellie Holden, who married Joseph C. Thomas; Ida Holden, married to Ralph S. Mott; and Joseph Sanford.

Cowles belonged to no religious denomination, but his son, Calvin D., wrote that his father "was deeply religious by nature, and would have gone to the stake for a principle or conscience's sake." Cowles was buried in Elmwood Cemetery in Charlotte, near the graves of three of his children, who died in infancy.