March 1808–17 June 1863

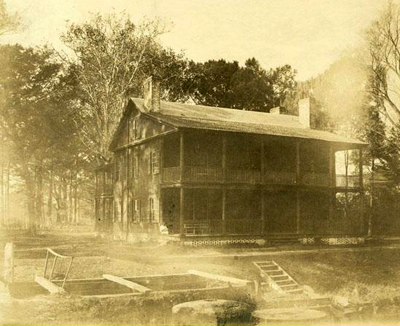

Josiah Collins, III, planter, the son of Josiah Collins II and his wife, Ann Rebecca Daves, was born probably in Edenton. Growing up with almost every conceivable advantage available to a youth in North Carolina at that time, the young Collins studied at Harvard and then read law at Litchfield, Conn. The completion of his education was signaled by his marriage to Mary Riggs of Newark, N.J., on 9 Aug. 1829. Ebenezer Pettigrew described the new Mrs. Collins as a "very amiable woman." Josiah Collins II spent some time preparing for the arrival of the newlyweds at Somerset Place on 5 Jan. 1830. Not satisfied with the two-story Colony House, the young Collins soon began construction of the large mansion that now constitutes the focal point of the Somerset Place State Historic Site.

Upon completion, the house became the setting for Collins's "aggressive type of hospitality," which some guests considered rather ludicrous. It was reported that "during a typical winter there were fourteen long-staying guests." Music, dances, and other sorts of entertainment were common during these periods. In the spring of 1857, for example, there were quadrilles every night. Despite their active social life, acquaintances described Mrs. Collins as reticent and her husband as increasingly moody and "domineering."

Collins quickly became politically active, though he apparently had little desire for public office. He served in the state senate for two sessions and was a member of the 1835 convention from Washington County. At the latter he was credited for being a "ready, skillful debator" and held the chair of the committee to arrange senatorial districts. He was a Harrison elector in 1840 and ran unsuccessfully for the House of Commons as a Whig from Washington County in 1850. The coming of the Civil War found Collins more than willing to defend his strongly anti-abolitionist stance.

The Collinses traveled north in the spring of 1830 for the birth of their first child, Josiah IV. Of their six sons only three, Josiah IV, Arthur, and George, survived their childhood at Somerset Place: Edward and Hugh drowned in the canal in front of the house on 2 Feb. 1843, and William Kent died in a riding accident some years later. The survivors all served the South during the Civil War.

Wintering at the lake and touring the springs in the summer, the Collinses considered themselves rather cultured. Indeed, in 1845 they attempted to adopt French as the household language. Collins enjoyed reading aloud to his children so much that he organized a Monday night reading club that was active from about 1855 to 1860.

As had been the case with his father, religion occupied an important part of Collins's life. He was especially interested in the religious activities of his slaves, frequently reading the services to them. In 1836 he erected a chapel on the plantation and engaged E. M. Forbes to convert the slaves from Methodism to his own Episcopal church, a three-year process. In 1857 the Reverend George Patterson read the services of morning and evening prayer at Somerset Place.

At first, things apparently did not go particularly well at Lake Phelps. The crops were badly damaged during 1835 and 1836, causing Ebenezer Pettigrew to criticize Collins for neglecting the farm and playing the role of absentee planter. However, after converting to corn as the main crop, Collins became one of the three largest slaveholders in North Carolina: in 1860 his more than 4,000 acres were worked by 328 slaves. Collins did not appear to distinguish himself in other business activities. In 1836 he attempted to produce silk with Pettigrew on Pea Ridge in the Albemarle Sound, but in 1842, after a deal with the Maryland Silk Company did not materialize, they began to liquidate their silk holdings.

The approach of the Civil War was an unhappy time for the Collins family. Collins became troubled by increasingly frequent headaches that served to make him more and more moody and erratic. Mrs. Collins suffered a stroke in 1860. Despite Collins's efforts to finance Washington County troops, the family and slaves were forced to flee Somerset Place, which fell in August 1862, for Hillsborough. The deserted plantation was frequently plundered throughout the duration of the hostilities. Collins died in Hillsborough shortly before the end of the war, and the efforts of Mrs. Collins and her sons to revitalize Somerset Place were unsuccessful. In 1870, two years before her death, Mrs. Collins sold the 4,428-acre holding to W. B. Shepard.