See also: Airmail Service; Airplane, First Flight of, History of Transportation from NCpedia Student Collection

The history of aviation and the airline industry in North Carolina encompasses more than Orville and Wilbur Wright's momentous flight at Kitty Hawk in December 1903. Before that, North Carolina inventors built and tried to fly several kinds of aircraft. Henry Gatling's 1873 hand-cranked monoplane in Hertford County and Daniel Asbury's 1881 steam-driven monoplane in Mecklenburg County were perhaps the best known. Jacob A. Hill built a dirigible at Winston-Salem in 1902, and Louis H. Kromm of Reidsville designed a huge dirigible the same year but was unable to finance it. In the wake of the first Wright brothers flight, North Carolina remained a leader in the field of aviation for nearly 20 years.

While the Wrights struggled at Kitty Hawk, Luther Paul of the Davis community in Carteret County designed and built a twin-rotor helicopter. In 1907 this machine, unmanned and tethered to the ground, lifted itself between four and five feet, making North Carolina the site of the world's first vertical as well as horizontal heavier-than-air flights. A model helicopter, built at Wilmington in 1910, was intended to lead to a full-sized machine, but the project failed.

Spurred by Louis Bleriot's 1909 flight across the English Channel and the onset of exhibition flying, North Carolinians between 1910 and 1912 built and flew six planes and projected over a dozen more. Wilmington and Charlotte craftsmen were responsible for at least five of those that were built, but only M. F. H. Gouverneur and Harold M. Chase's four-winged multiplane actually flew (on 10 Nov. 1910 at Shell Island near Wilmington). A Santos-Dumont "Demoiselle" monoplane, built by three Kinstonians in 1911, failed to fly because of its underpowered automobile motor. Greensboro's W. F. Johnson in 1910 became the first African American to design an aircraft (an electric biplane), but only a model was built.

While these and other projects-including David Palmgren's unique "aero-car" at Wilmington-proceeded within the state, two North Carolinians who went north seeking greater industrialization and ready capital achieved more impressive results. William W. W. Christmas, a Warrenton native, claimed to be the first American after the Wrights to build and fly a plane (in northern Virginia in March 1908). The claim was never validated, but he built biplanes at College Park, Md., in 1910 and 1912; both achieved successful flights. In 1914 Christmas took out the first patent on an inset aileron, a device used by virtually every plane since that time. Meanwhile, Lenoir's James S. Spainhour built and flew a "self-balancing" biplane near Pittsburgh in 1911. By the 1920s, aircraft building had become too complex and expensive to be a large-scale industry in North Carolina. Small companies built planes at High Point, Asheville, and perhaps elsewhere, but the major expansion of the industry took place outside the state.

Exhibition flyers roared into North Carolina in 1910, beginning with flights by Eugene Ely and J. A. D. McCurdy in Curtiss planes at Raleigh on 16 November. Lincoln Beachey gave an exhibition at Wilmington on 9 Mar. 1911 and briefly opened a flight school at Pinehurst for the golfing set that spring. He flew at Durham, Asheville, Greensboro, Winston-Salem, and other towns, generating huge popularity for aviation. Charles C. Witmer, Charles F. Walsh, Harry LeVan, and J. B. McCauley were among numerous others who exhibited in North Carolina prior to 1914. In 1913 Tiny Broadwick of Oxford became the first woman to parachute from an airplane. At Greensboro in 1911, entrepreneur Lindsey Hopkins of Reidsville started the Lindsey Hopkins Aviation Company, paid for the flight lessons of auto mechanic Thornwell H. Andrews of Charlotte, bought a Curtiss airplane, and sponsored exhibitions across the country.

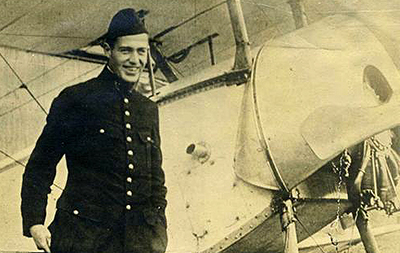

Because many of its youth were familiar with cars and planes, the state contributed more than 300 pilots to World War I. Reidsville's Opie Lindsay shot down six German planes to qualify as an ace, and James McConnell of Carthage and Kiffin Rockwell of Asheville founded the Lafayette Escadrille, volunteers who fought for France before America entered the war in 1917. Both died in air battles.

In 1918 the U.S. Navy established a seaplane base at Morehead City and the Signal Corps Air Service began work on Pope Field near Fayetteville. The Carolina Airplane Company, founded in 1918 by veteran pilot Harry Atwood, built Curtiss seaplanes at Raleigh, Smithfield, and Goldsboro, but they proved to be underpowered and the navy rejected them. Planes were assembled and flown at Camp Greene, outside Charlotte. Also in 1918 Christmas designed and built what he expected to be America's first pursuit plane, the "Christmas Bullet," but two prototypes crashed, killing their pilots.

Belvin Maynard of Harrell's Store was regarded by many as the world's best pilot at the war's close. A test pilot during the conflict, Maynard set an as-yet unchallenged record in early 1919 by performing 318 consecutive inside loops in 67 minutes with a Sopwith Camel at a French airfield. He was home in time to fly in the army's round-trip endurance races between Long Island and Toronto and across North America that fall, the longest air races held to that time. Maynard won both events, the second despite a forced landing in rural Nebraska and the overnight replacement of his burned-out engine. He died in a Vermont air crash in 1922.

As air travel developed from experimental to military to commercial use in the twentieth century, many airlines have served North Carolina travelers. Piedmont Airlines, founded by Tom Davis in Winston-Salem on 1 Jan. 1948, became one of the nation's leading carriers. The airline grew out of Piedmont Aviation, Inc., established by Davis in July 1940 as a sales and service outlet for the Southeast's burgeoning aircraft business. Authorized to begin operations by the Civil Aeronautics Board on 4 Apr. 1947, Piedmont made its first flight on 20 Feb. 1948 from Wilmington to Cincinnati, Ohio. There was one paying passenger on board, a man named Bill Turner, and his fare was $34.35.

Limited by government regulations to regional routes during the daytime, Piedmont nonetheless thrived. By 1958 it was carrying nearly 200,000 passengers annually, and within another four years it was granted access to Atlanta from its bases in Columbia, S.C.; Washington, D.C.; and Baltimore. The number of passengers carried annually rose to 664,000. In November 1966 Piedmont inaugurated flights to New York's La Guardia Airport; within three years it was carrying more than 2 million passengers a year. Within a decade it added routes to Miami, Tampa, and Boston.

Truly phenomenal growth occurred in the wake of the federal government's decision in August 1978 to deregulate the nation's air carriers. Liberalized route and fare policies meant that strongly positioned regional carriers like Piedmont could branch out quickly and competitively. Los Angeles, Denver, Dallas, San Francisco, and Phoenix were added to Piedmont's system; in less than a decade the airline inaugurated international service with flights to London. The immediate consequence of deregulation was a dramatic increase in Piedmont's size as an airline and in its number of passengers. In 1969 it served 78 cities and carried 2.2 million passengers. In 1984 it carried 13 million passengers and passed the $1 billion mark in revenues. By 1987 it was carrying 23 million passengers a year to 235 destinations.

By the time of deregulation, however, Piedmont's future was becoming more uncertain. Despite Davis's long-held belief that growth was best achieved internally, Piedmont was an increasingly attractive target in a number of take-over bids. The first, launched by Air Florida in 1978, failed. Next came the Norfolk & Western Railroad, which offered $1.5 billion and $65/share for the airline in 1986. That bid was upset by US Airways's subsequent bid of $1.6 billion, based on stock buyouts ranging from $68/share to $71/share. On 9 Mar. 1987 the merger between US Air and Piedmont was announced, a decision that created the nation's seventh-largest air carrier.

Aviation has allowed for much faster travel for North Carolinians and other Americans, but it has sometimes resulted in the tragic loss of lives. The first crash of a commercial aircraft in North Carolina occurred near Bolivia on 6 Jan. 1960, involving a National Airlines flight from New York to Miami. The plane had just passed Wilmington and was over the ocean when a bomb exploded on board. Despite the damage, the plane headed back toward Wilmington. Before it could reach the airport, however, the plane disintegrated and crashed, killing all 34 people on board. The bomb had been carried onto the plane by passenger Julian Frank of New York, who was in a web of complicated business deals and under investigation by the district attorney for embezzlement. A few months earlier, he had taken out nearly $1 million in life insurance. His death was ruled a suicide and his wife did not collect.

On 19 July 1967 a Piedmont Boeing 727 and a private Cessna 310 collided near Hendersonville. All 79 people in the jetliner and all 3 in the Cessna were killed. The Piedmont flight had just taken off from Asheville when the Cessna, preparing to land, crashed into it. On board the jet was secretary of the navy designate John T. McNaughton, who was to be sworn in a week later. The collision was a result of pilot confusion and unclear air traffic control instructions.

The state's largest air accident to date occurred on 11 Sept. 1974, when an Eastern Airlines DC-9 crashed while attempting to land at Charlotte. Of the 82 people on board, 71 died, including CBS news editor John Merriman. There was patchy fog as the plane tried to land, but the primary cause of the wreck was error by both pilots (one of whom survived). Other tragic airplane accidents in the state include the July 1994 crash of a US Airways DC-9 near Charlotte, killing 37 people, and the December 1994 crash of an American Eagle Jetstream Super 31 four miles southwest of Raleigh-Durham International Airport, in which 15 of 20 passengers died.

North Carolina airports have gained and then lost several airline hubs through the years, in particular those of American Airlines and Midway Airlines (both located at Raleigh-Durham International Airport). Today, North Carolina's major carriers include United, Delta, Southwest, and US Airways (which has a hub in Charlotte). The state has about 75 publicly owned airports and nearly 300 more that are privately owned. There are also approximately 50 flight schools in North Carolina, educating the state's more than 15,000 privately licensed pilots. Nine airports have regularly scheduled airline service, and four are international (Charlotte/Douglas International Airport, Raleigh-Durham International Airport, Wilmington International Airport, and Greensboro-Piedmont Triad International Airport). By the early 2000s, more than 35 million passengers flew to and from North Carolina each year, and more than 800 million pounds of air freight originated annually in the state.