See also: Asheville Armory.

References to armories, where matériel for common defense is stored and used in training troops, appear at various times in the records of Asheville, Edenton, Fayetteville, Salisbury, Wilmington, and other North Carolina locations. In 1755, for example, during the French and Indian War, the Assembly asked the governor "to appoint some person to provide a sufficient Store House for . . . safe keeping the Arms sent by his Majesty for the Use of this province and keep the same clean and in good Order."

On 15 June 1776 the Council of Safety authorized the treasurer to pay James Dupree £150 to purchase tools for an armory that would serve Continental troops in North Carolina. Governor Richard Caswell's correspondence at this time suggests that munitions were manufactured there. After the Revolutionary War North Carolina congressman Hugh Williamson pointed out that the Continental Congress had built arsenals in the North but none in the South, and there was concern about the disposition of North Carolina's share of remaining military supplies; the state worried about potential attacks by Indians or the Spanish.

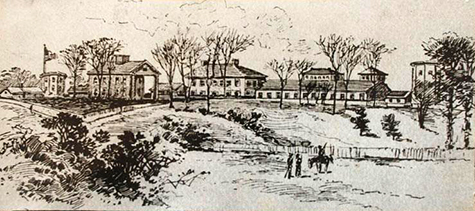

In an effort to strengthen the new republic's defenses after the War of 1812, more than 20 arsenals were approved for the Atlantic coastline, including one at Fayetteville. In 1836 the U.S. Congress made the initial appropriations for this site, officially named the North Carolina Arsenal, and the cornerstone for the first building was laid on 19 Apr. 1838. The arsenal was completed in 1859 after various periods of construction, although poor transportation left it largely unused except for the storage of vintage arms.

In April 1861 Governor John Ellis rejected President Abraham Lincoln's request for troops and ordered the seizure of all Federal property in North Carolina. The capture of 37,000 stands of arms stored at the arsenal provided weapons for thousands of volunteers. Acting on Ellis's offer to transfer the North Carolina Arsenal to the Confederacy, President Jefferson Davis requested that Virginia loan the Harpers Ferry rifle machinery to North Carolina for use at Fayetteville. In July 1861 a Confederate officer was ordered there to take command of the newly named Fayetteville Arsenal and Armory for the government in Richmond.

The arsenal was expanded far beyond its original boundaries to utilize large amounts of captured machinery. Surpassed only by facilities in the Confederate capital, Fayetteville became the second most important source of rifles in the South; as many as 10,000 rifles were made there during the war. The arsenal was razed during William T. Sherman's occupation in March 1865. By the early 2000s the buildings and grounds of the Museum of the Cape Fear covered part of the site.

The Wilmington Armory began as a Greek Revival-style house built about 1847 for James Allan Taylor, a shipping and railroad industrialist, city alderman, president of the Wilmington Bank, and a director of Oakdale Cemetery. The structure, designed by Benjamin Gardner, was valued at $40,000 in 1850. In 1876 it became the property of Charles Stedman, a former Confederate army major who later was lieutenant governor of North Carolina and ultimately a U.S. congressman.

On 16 May 1893 the house was acquired by the Wilmington Light Infantry (WLI), the state's second oldest military organization, dating from 1853. The militia group, which eventually became part of the Army Reserve Corps and National Guard, served in every war from the Civil War through World War II. The WLI used the building as its armory until 1951, when the city of Wilmington bought it for use as a public library, reserving a room in the basement for meetings and social gatherings. The WLI added to the landmark by placing small cannons on the roof.

In 1981 city planning and development offices replaced the New Hanover County Public Library. New federal laws requiring physcially accessible public buildings forced the city to sell the building in 1996 to neighboring First Baptist Church. The sale stipulated that the WLI could continue to meet in the building until its last member died.

As a part of the federal program for economic recovery in the 1930s, National Guard armories were among the buildings planned for construction to provide employment for out-of-work men. The armories proved to be useful when state troops were called into national service. Afterward, they provided a site for functions such as concerts, lectures, athletic events, and rallies.