American Indian Tribes in North Carolina

American Indian Tribes in North Carolina

Originally published as "The State and Its Tribes"

by Gregory A. Richardson

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian, Fall 2005.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

See also: Native American Settlement; North Carolina's Native Americans (collection page)

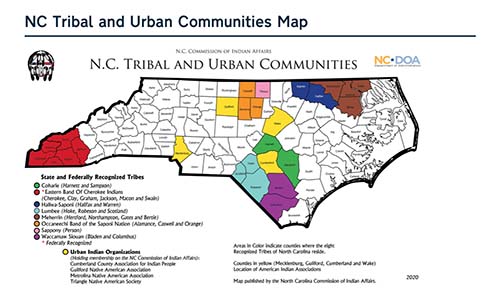

North Carolina has the largest American Indian population east of the Mississippi River and the eighth-largest Indian population in the United States. As noted by the 2000 U.S. Census, 99,551 American Indians lived in North Carolina, making up 1.24 percent of the population. This total is for people identifying themselves as American Indian alone. The number is more than 130,000 when including American Indian in combination with other races. The State of North Carolina recognizes eight tribes:

- Eastern Band of Cherokee (Tribal lands in the Mountains including the Qualla Boundary)

- Coharie (Sampson and Harnett counties)

- Lumbee (Robeson and surrounding counties)

- Haliwa-Saponi (Halifax and Warren counties)

- Sappony (Person County)

- Meherrin (Hertford and surrounding counties)

- Occaneechi Band of Saponi Nation (Alamance and surrounding counties)

- Waccamaw-Siouan (Columbus and Bladen counties)

North Carolina also has granted legal status to four organizations representing and providing services for American Indians living in urban areas: Guilford Native American Association (Guilford and surrounding counties), Cumberland County Association for Indian People (Cumberland County), Metrolina Native American Association (Mecklenburg and surrounding counties), and Triangle Native American Society (Wake and surrounding counties).

The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians is the only North Carolina tribe officially recognized by the federal government. The federal Lumbee Act of 1956 recognized that tribe in name only.

Some may think of treaties involving land as the only example of government relationships with Indians over the years. But the General Assembly’s creation of the N.C. Commission of Indian Affairs in 1971 offers strong evidence that the state has a positive relationship today with its American Indian citizens, tribes, and groups. The relationship between North Carolina and its tribes is well documented in statutes; in rules and regulations that govern state funded programs; and in rules associated with historic Indian schools, court rulings, and faith organizations. The modern federal government has likewise recognized North Carolina’s rich American Indian heritage and history.

The benefits of state recognition range from being eligible for membership on the Commission of Indian Affairs and for program funding, to securing a rightful place in history. Since 1979 the commission has coordinated procedures for recognition. A committee of members from recognized tribes and groups reviews applications. Tribes and groups must meet certain organizational requirements. Criteria that then may be used to support an application for recognition include traditional North Carolina Indian names; kinship relationships with other recognized tribes; official records that recognize the people as Indian; anthropological or historical accounts tied to the group’s Indian ancestry; documented traditions, customs, legends, and so forth that signify the group’s Indian heritage; and others.

The creation of institutions such as Pembroke Normal School and East(ern) Carolina Indian School offers an example of the historic relationship that Indians have had with this state. The reservation lands currently held in trust for the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and the Historic Tuscarora Indian Reservation in Bertie County are examples of formal relationships between Indians and the federal government. Today, because 10,350 American Indian students attend public schools in the county, the Public Schools of Robeson County administers one of the largest Indian education programs in the nation, funded by the U.S. Department of Education. Statewide, 19,416 American Indian students attend public schools. The Haliwa-Saponi tribe has reestablished the old Haliwa Indian School in Warren County, which the author attended through the ninth grade. The new Haliwa-Saponi Tribal School is a charter school, attended by about 150 students. Such arrangements, or ongoing government-to-government relationships, offer examples of modern-day treaties with American Indians.

The situations of Indians differ from state to state. The United States has more than 550 federally recognized tribes and forty to fifty state-recognized ones. In North Carolina and nearby states, most Indians are members of state-recognized tribes and do not live on reservations. The latter is much the case nationwide, according to the 2000 U.S. Census, which found that more than 62 percent of Indians live off reservations. In Virginia there are three reservations, none of which is recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA); BIA does not provide the tribal members services or funding for such things as health care, schools, police, or fire protection. The tribes are not authorized to establish casinos or other gaming enterprises that federal recognition allows as an economic development tool. In North Carolina, only the Eastern Band of Cherokee tribe is eligible to receive BIA services and to operate a casino. In South Carolina, only the Catawba tribe has this status.

American Indians have long been studied and researched, especially by the academic community; however, for many years, little of that information found its way into history books. There are volumes of information on file about American Indians at North Carolina’s college campuses; only recently has much material begun to be included in textbooks used in public or private schools. Indians constantly question the common practice of focusing on Plains Indians in books and in popular media such as movies or television programs. The history and culture of Eastern Woodland Indians often get overlooked.

In North Carolina, before the Civil Rights era, Indians experienced discrimination and different forms of racism. At one time, some were discouraged to even admit that they were Indians. In several counties, separate schools were established for American Indians. These schools, built by volunteers and paid for by the Indian community, were small, mostly of one or two rooms. In some of these same counties, separate dining and other public facilities for the races were common before the 1960s; often, there were no “Indian” facilities—only “white” and “colored.” For a long time, limited employment opportunities existed for American Indians.

Today’s American Indians enjoy more opportunities. Their culture, heritage, and accomplishments are shared more often in and outside their communities. And the North Carolina government continues to increase its support of the many efforts of the state’s first inhabitants.

At the time of the publication of this article, Gregory A. Richardson was the executive director of the N.C. Commission of Indian Affairs. He is a member of the Haliwa-Saponi tribe. He served as one of the conceptual editors for the Fall 2005 issue of Tar Heel Junior Historian.

Educator Resources:

Grade 8: 8 Tribes, 1 State: Native Americans in North Carolina. North Carolina Civic Education Consortium. http://civics.sites.unc.edu/files/2014/06/NCNativeAmericans.pdf

References and additional resources:

Resources in NCpedia: Lumbee Indians; Haliwa Indians; Sappony Indians; Meherrin Indians; Occaneechi Indians; Waccamaw Indians; Cherokee Indians.

American Indian Timeline from the NC Museum of History.

Image Credit:

N.C. Commission of Indian Affairs. "N.C. Tribal and Urban Communities." 2020. https://ncadmin.nc.gov/about-doa/divisions/commission-of-indian-affairs

1 January 2005 | Richardson, Gregory A.