The Sappony are a Souian tribe, along with the Waccamaw, Occaneechi, and Enos.

General Information

The Sappony are the only North Carolina tribe whose traditional homelands, the High Plains of the Piedmont region, cross the border of another state. They settled the area straddling Person County, North Carolina, and Halifax County, Virginia before state lines were drawn, and in fact, helped draw the boundary line in 1728 when Sappony Ned Bearskin led William Byrd’s surveying party through the region.

The Sappony Tribe is governed in the traditional way: a council consisting of one elected representative from each of the tribe’s seven families leads the tribe. A tribal chair and chief lead the council. An executive committee helps with the daily business of the tribe. Committees address specific community concerns such as education, cultural and public relations, and economic development. All positions in the tribe are voluntary.

The Sappony were legislatively recognized by the state of North Carolina in 1911 and by the state of Virginia in 1913 and had about 850 tribal members as of 2011.

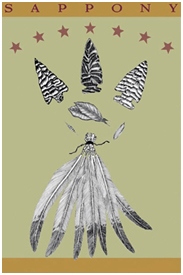

Because tobacco was historically a primary subsistence crop, the Sappony placed a tobacco leaf in the center of their Tribal insignia. The insignia also shows corn and wheat flanking the tobacco. Corn and wheat were two other crops that along with tobacco formed the base of Sappony subsistence. The seven feathers represent the seven families tied together; the seven stars, the seven families under God. The arrowheads echo a colonial trading symbol used by the Sappony.

Sappony history is one of family bonds, hard work, moral values and loyalty. It is the history of a people whose lives changed with the changing of times — from hunters and farmers of pre-contact days to trading partners with the English during colonial times, from tenant and landed farmers throughout the 1800s and 1900s to a contemporary Indian people in a diversified world today.

Current Initiatives

The Sappony are currently pursuing initiatives in the areas of economic development, health, education and cultural preservation. They hold annual tribal events, such as Homecoming, a spring event, and a Fall Stew, and are involved in Native American health and education issues and organizations. Additionally, their summer youth camp is included in their Heritage Program.

History

At the beginning of the 1600s, Sappony Indians were living in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. They lived near some of their Siouan relatives.

In 1607, explorer John Smith asked the Algonquian-speaking Powhatan Indians about their native neighbors to the west. He was told of five villages along the western James River — Monahassanugh, Rassawek, Mowhemencho, Monassukapanough, and Massinacack. The Indians of Monassukapanough later became known as the Sappony.

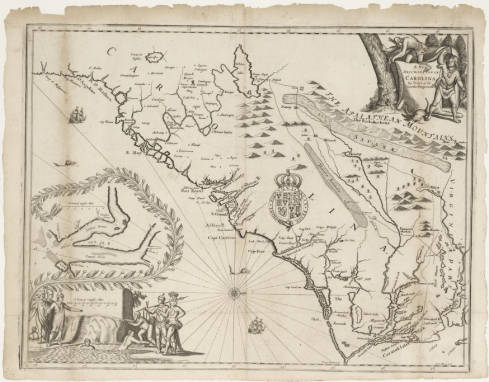

The early map of eastern North Carolina and Virginia by John Ogilby features the towns and places visited by the explorer John Lederer, in 1669 and 1670. The map shows the ancestral Sappony towns of Sapona and Nahisan as well as the island town of Akenatzy (Occaneechi). Lederer described the various tribes living in the Piedmont as “distinguished into several Nations of Mahoc, Nuntaneuck, Nutaly, Nahyssan, Sapon, Managog, Mangoack, Akenatzy, and Monakin, etc.”

Though the exact locations of these towns are unknown, Lederer’s travels shown on the Ogilby map confirm that in the early 1670s the Sappony were still in the Virginia Piedmont, somewhere north of Occaneechi Island.

Between 1671 and 1772 the Sappony and Tutelo moved away from the Virginia foothills to avoid Iroquoian enemy attacks. They settled with the Occaneechi on islands at the junction of the Staunton and Dan rivers, near present day Clarksville, Virginia. This island location allowed the Indians to benefit from trade between the English settlers and other Indian tribes to the west.

Bacon’s Rebellion

In 1676 these Indians became involved in Bacon’s Rebellion, a war that began with conflicts between the English and the Iroquoian Susquehannocks. The English and several Indian tribes friendly to the colonists, including the Sappony, signed a treaty at the end of the war. This Treaty of Middle Plantation changed the relationship of the Sappony and their allies with King Charles of Great Britain and with the English colonials. Now the government recognized the Sappony as a “tributary tribe,” meaning they agreed to maintain peace with the colonists and pay a yearly tribute in fur and skins. For this, they were guaranteed homeland and protection by the Colonial government.

Following Bacon’s Rebellion of 1676, despite assurances of protection and peace from the colonial government, the Sappony and many of their Siouan allies faced threat from hostile colonists and enemy Iroquoian tribes. They chose to leave the south-side Virginia area and move to safety in North Carolina. The Sappony joined their Siouan cousins, the Catawba, at the Trading Ford along the Yadkin River.

In 1701, explorer John Lawson encountered the Sappony while they were living on the Yadkin. He commented that the Sappony King was “a good Friend to the English.” Lawson also said that the “Toteros, Saponas, and Keyawees… were going to live together, by which they thought they could strengthen themselves…” Shortly after Lawson’s encounter with the Sappony, some of the tribe moved and settled Sapona Town, fifteen miles west of present-day Windsor, North Carolina.

Fort Christanna

By 1708, the Sappony returned to south-side Virginia, but by this time Virginia colonists occupied their former Sappony tribal lands. So they settled east of present day Emporia, Virginia. Then in 1714, under the direction of Governor Alexander Spotswood, the colonial government set aside a six-mile square tract of land on the south side of the Meherrin River in what is today Brunswick County, Virginia, near Lawrenceville. Alongside this land, Spotswood constructed a fort, Fort Christanna, to protect the Sappony and their Siouan allies.

Fort Christanna was built at what was then the western frontier of Virginia and served many purposes. It was a place where the Virginia Company conducted fur trade with the Indians. Indian children were taught English and Christianity there. And the fort protected the Virginia frontier settlers and the friendly Indian tribes from hostile Indian attacks. During this period, Governor Spotswood began referring to the Sappony, the Tutelo, and the Occaneechi collectively as the “Sappony.”

In 1718 after Governor Spotswood lost funding for Fort Christanna, the fort was closed and the Sappony dispersed. Some of the Indians stayed in the Fort Christanna area while others moved to various communities in the Piedmont.

The Dividing Line

The North Carolina Piedmont was as familiar to the Sappony as their Virginia homelands. When William Byrd surveyed the Virginia-North Carolina Piedmont border in 1728, he was led by a Sappony guide, Ned Bearskin, who was residing near Fort Christanna. Bearskin guided Byrd and his surveying party through the Piedmont from Currituck Sound on the North Carolina shore to the Dan River, the western frontier of these states at that time.

Time of transition

After the closing of Fort Christanna, the Sappony established several communities. Some stayed in the Christanna area. Others settled along the trading path in what is now Dinwiddie County, Virginia. From this community, the descendants of several families of the High Plains Indian Settlement can trace their heritage.

The 1730s and 1740s were a time of transition for the Sappony. For a short time in the 1730s some Sappony lived again with the Catawba. Around 1740, some of these Sappony moved north to New York. Others however, followed the traders into a community on both sides of the Meherrin — the Flat Rock Creek settlement — in current Lunenburg and Mecklenburg Counties.

After the American Revolution, members of the Flat Rock Creek community began a migration into North Carolina. The Sappony moved south into present-day Person County, North Carolina, a safe and isolated area near the ancestral trading path that they had used since at least the 1670s. This is the same area Ned Bearskin had guided William Byrd through in 1728. After 1800, there was a gradual increase in the number of Sappony in the High Plains area.

Making High Plains Home

Transitioning from agricultural subsistence

For over two centuries, the Sappony living in High Plains grew tobacco as a primary subsistence crop, as well as corn and wheat. This, along with their Indian church and school, allowed the community to remain self-sufficient. The tribal insignia features a tobacco leaf because of its importance to the tribe. Today, tobacco farming in the region is no longer economically viable. Tribal members now pursue higher education and have become skilled in a variety of fields, currently working in many professions other than farming including education, medicine, finance and technology.

School and Church

The church has always been the center of the Sappony community. It has been a place to meet, worship, and was even used for education before a separate school was built. The current Calvary Baptist Church is in Person County, North Carolina.

The first school began as one room in the Baptist church in Halifax County, Virginia in 1878. In 1911, the Sappony built and funded the High Plains Indian School in its final location in Person County, North Carolina after receiving legislative recognition from the state of North Carolina. Virginia state recognition and funding followed in 1913. The states paid for the teachers and the books; the community was required to build the school and playgrounds. By 1958 the school had expanded to six rooms. The High Plains Indian School eventually had classes for all grades through high school. In 1962 the school was closed with the advent of assimilation and the children were sent to other area schools.

Mid-Twentieth Century to Today

Life changed for the Sappony as the century neared its mid-point. Some fought in World War II and the Korean War, taking them away from the community for the first time. Graduates of High Plains School began to leave the community for jobs or to further their education.

The 1960s changed things for the Sappony community as it did for the rest of the nation. The closing of the High Plains School and dispersion of the Sappony children to other schools brought greater contact with the world outside the isolated Sappony community for all Tribal members.

However, their ongoing commitment to community and family has kept them together. Those who have remained in High Plains have maintained the family homes and farm lands. Relatives who have moved from the area continue to come back for yearly family reunions, school reunions, and Sappony homecomings. Keeping the family stories and reconnecting with their early history has become a passion for many Sappony. Following this time of change, leaders in the community began efforts to document Sappony history and to reclaim their Indian heritage.

In 2003, the Sappony officially changed their name from the state-designated label of “Indians of Person County” to the current “Sappony” to more accurately reflect their heritage.

In recent years the tribe has made efforts to obtain federal recognition, educate others about their heritage, and create resources for maintaining their community through economic development and their Heritage Program, which includes a youth camp that began in 2001. Education remains of utmost importance to the Sappony, and their Education Committee awards annual scholarships to encourage and reward post-high school studies.