Anglican clergyman Thomas Bray is commonly credited with establishing the first public library in North Carolina. Bray arrived in the colony to recruit clergy to return to Maryland but found the population mostly poor and uneducated. In response, he joined with the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts to send, on 2 Dec. 1700, 36 titles for a layman's library and 148 titles for a parochial library. It was not until after the American Revolution that several additional private, parochial, and associated libraries were founded in North Carolina. Between 1794 and 1848, 32 library societies were incorporated by the General Assembly.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the census declared that North Carolina had the highest illiteracy rate in the nation. In response, Charles C. Jewett, librarian of the Smithsonian Institution, decided to donate several thousand volumes to various North Carolina libraries. At the same time, the North Carolina secretary of state began building a collection of books in his office that evolved into the State Library; formally established in 1812, this State Library was the only tax-supported library existing in North Carolina before the twentieth century. The Library Commission, an advisory body to the secretary of the Department of Cultural Resources regarding State Library operations and programs, traces its origin to the 1871 legislation creating a board of trustees for the State Library and to the late nineteenth-century movement for expanded public libraries.

In 1867 North Carolina's first free library, named the Good-Will Free Library, was opened by Charles Hallet Wing in Ledger (Mitchell County). This library, which remained in existence until 1926, opened with 12,000 volumes. By 1886 there were 22 libraries of more than 300 volumes each in the state. All but four-the library at the Insane Asylum, the State Library, the State Law Library, and the Library Association in Wilmington-were located at schools, colleges, and universities. In the late 1890s, the growth of industrialization resulted in an increase in leisure time, allowing Americans to indulge in more intellectual pursuits. Consequently, more libraries were called for on a national level. In addition, a new school of thought had evolved that claimed the best means of preventing social disorder was the development of formal public institutions. Rooted in an agrarian culture, North Carolina was affected by such ideas later than the rest of the country. On 9 Mar. 1897 the General Assembly ratified an act requiring any town of more than 1,000 people to provide for the establishment of a public library. By 1900 North Carolina had 57 libraries. Grants from industrialist Andrew Carnegie and the Carnegie Corporation supported the building of ten more libraries, located in Greensboro, Charlotte, Winston-Salem, Andrews, Durham, Hendersonville, Hickory, Murphy, and Rutherford College.

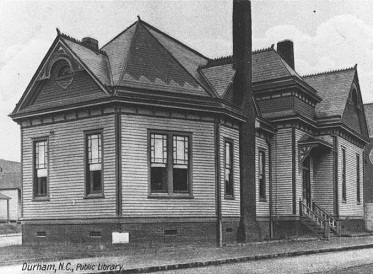

The Durham Public Library, the first free, tax-supported public library in North Carolina, began as an idea discussed by Professor Edwin Mims of Trinity College (now Duke University) with the Canterbury Club, a local literary club, in June 1895. Lalla Ruth Carr and her father, industrialist and philanthropist Julian Shakespeare Carr, solicited support for the establishment of the library. Julian Carr, along with Mrs. Thomas H. Martin, donated the land for the library. On 5 Mar. 1897, an act incorporating the Durham Public Library was passed by the North Carolina General Assembly. The library was finished in January 1898 and opened its doors to the public in early February of that year. Prior to 1900, fewer than 2 percent of all of the nation's tax-supported public libraries were located in the Southeast. Other public libraries in North Carolina began as subscription libraries. These lending libraries charged borrowers a membership fee instead of, or in addition to, a specific charge for books borrowed. Many subscription libraries became tax-supported in the early 1900s.

In Greensboro a small group of citizens banded together to form the Library Association on 4 May 1904. This association later spurred the passage of a 1909 legislative act that established an official North Carolina Library Commission to open and give assistance to libraries, including the establishment of traveling libraries. Traveling libraries consisted of collections of books loaned to smaller towns and rural areas where no library facilities existed. Each traveling library contained 30 to 40 volumes, equally divided between fiction, nonfiction, and children's books. The books were placed in special wooden cases that, when opened, doubled as display shelves. Each traveling library was loaned to a town or rural area for three months at a time then returned and replaced by another collection. Supported by the North Carolina Federation of Women's Clubs, eight traveling libraries circulated in 15 North Carolina counties beginning in 1909. By the mid-1920s, there were 1,275 traveling libraries consisting of at least 40 books sent to over 865 locations in North Carolina. As regular library service expanded, traveling libraries dwindled to only 260 by 1944.

Despite the increased availability of libraries and books, by 1926 only 32 percent of the state had ready access to public libraries. Under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the New Deal Works Project Administration approved a statewide library project in North Carolina with Julius Amis as the head. By 1942 the percentage of North Carolinians with library access had increased to 85 percent. President Dwight Eisenhower's 1956 Library Services Act helped extend services to the remaining rural parts of North Carolina that were without services. The Library Services and Construction Act a decade later served to promote interlibrary cooperation and provide library services to the elderly.

The Citizens Library Movement of the 1960s was a widespread effort to further improve North Carolina's public libraries through the coordinated actions of support groups in each of the state's 100 counties. It began in early 1964, when Governor Terry Sanford appointed 39 educators, bankers, editors, authors, librarians, and other library supporters to a Governor's Commission on Library Resources. The commission's charge was to make a comprehensive survey of all types of library resources in the state, measure these resources against present and future needs, and produce recommendations to point the way "for all citizens and agencies to take steps toward meeting the state's growing and changing library needs." A key finding of the commission, stated in its 1965 report, was that average expenditures for public libraries in North Carolina fell far below the national average. To a large extent this was due to the fact that the methods employed in financing public libraries in the state had evolved throughout the years on a piecemeal basis with no clear-cut and understandable statewide financing plan. The commission's primary recommendation was for the formation of a Statewide Citizens Committee for Better Libraries.

At its biennial meeting on 5 Nov. 1965, the North Carolina Association of Library Trustees took up the challenge issued by the Governor's Commission on Library Resources. A steering committee was named, and by early 1966 an organization known as North Carolinians for Better Libraries (NCBL) had been formed with the goal to "help local libraries help themselves." Soon a state headquarters had been established in Raleigh, and members were being recruited in every county. By the spring of 1967, there was an NCBL representative in each county and active local library support groups in many of them, all coordinating their actions through the Raleigh office. One of the major accomplishments of this unified effort was the creation of the Legislative Commission to Study Library Support in the State of North Carolina. The emphasis of this five-member commission (made up of two state senators, two state representatives, and a chairman appointed by the governor) was to study the pattern of library financing in the state. The commission was to report back to the General Assembly in 1969 with recommendations for more equitable and adequate financing of public libraries.

The governmental reorganization acts of 1971 and 1973 ultimately transferred the Library Certification Board, which holds the power to establish libraries, to the Department of Cultural Resources. Interest in library development diminished as the majority of the state gained access to adequate library resources. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the State Library had become a leader in the improvement of library services on a national level.