North Carolina’s Youngest Soldiers: The Junior Reserves

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

As the Civil War raged on, the Confederate States of America faced a shortage of men to fill the ranks of its armies. In 1862 the Confederate Congress passed a conscription, or draft, law that set the age range of men required to serve in the military to 18–35. The army discharged younger or older men who had volunteered earlier. A second law passed later in the year raised the age limit to 45. Officials still granted many men exemptions from service, for a variety of reasons, or assigned them to work in industries important to the war effort. A third conscription law passed in early 1864 brought many men into the army who had previously not been required to serve.

1862 the Confederate Congress passed a conscription, or draft, law that set the age range of men required to serve in the military to 18–35. The army discharged younger or older men who had volunteered earlier. A second law passed later in the year raised the age limit to 45. Officials still granted many men exemptions from service, for a variety of reasons, or assigned them to work in industries important to the war effort. A third conscription law passed in early 1864 brought many men into the army who had previously not been required to serve.

One provision of the 1864 law required 17-year-olds and men ages 45 to 50 to join up. Volunteers could organize into units made up of individuals in their age group. The boys were known as the Junior Reserves, while the older men became the Senior Reserves. Those who did not volunteer for these Reserve units were drafted into regular combat units instead. When a member of the Junior Reserves reached his 18th birthday, he was supposed to transfer into a combat unit.

Junior and Senior Reserve units guarded key military points—such as bridges, railway depots, and prison camps—in the states in which they were organized. This released soldiers who previously performed those duties to be with the armies in battle. Officials did not intend for the Reserves to fight, with the possible exception of repelling raids against their posts. Reserves also were not supposed to leave the states where they had been recruited. Officials suspended this rule near the end of 1864, as things grew even more desperate for the Confederacy. The North Carolina Junior Reserves, in fact, briefly went to Virginia on two occasions.

The Junior Reserves of North Carolina originally were organized into eight battalions of three to four companies each. Over the next several months, all but one battalion were consolidated into three regiments, consisting of the standard size of 10 companies each. The members of the remaining battalion came from the Mountain region and foothills, while Junior Reserves in the regiments hailed from the eastern and Piedmont portions of the state.

Unfortunately, gaps in the records prevent us from knowing exactly how many boys served in the state’s Junior Reserves. There are surviving wartime records for just over 4,000 youths. Additional postwar records provide almost 400 more names, and many more certainly served.

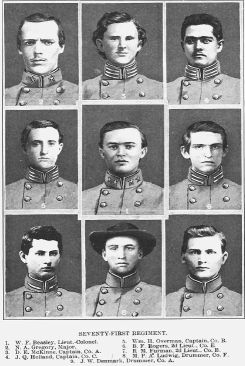

In order to provide mature leadership for these young soldiers, older men acted as the battalion and regimental commanders of Junior Reserve units, as well as on their staffs. The one exception was Walter Clark, a young graduate of the University of North Carolina who had been a drill instructor and staff officer for various combat units. Clark was still only 17 when he was elected major of the Sixth Battalion N.C. Junior Reserves in May 1864. When the Sixth Battalion was consolidated with another battalion to form the First Regiment N.C. Junior Reserves that June, Clark was elected major of the new unit. Clark became a judge after the war. In 1901 he edited the series Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War 1861–’65, one of the earliest efforts to document the role played by the state in the Civil War. Some Junior Reserves officers, particularly at the company level, were only a few years older than their men.

In order to provide mature leadership for these young soldiers, older men acted as the battalion and regimental commanders of Junior Reserve units, as well as on their staffs. The one exception was Walter Clark, a young graduate of the University of North Carolina who had been a drill instructor and staff officer for various combat units. Clark was still only 17 when he was elected major of the Sixth Battalion N.C. Junior Reserves in May 1864. When the Sixth Battalion was consolidated with another battalion to form the First Regiment N.C. Junior Reserves that June, Clark was elected major of the new unit. Clark became a judge after the war. In 1901 he edited the series Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War 1861–’65, one of the earliest efforts to document the role played by the state in the Civil War. Some Junior Reserves officers, particularly at the company level, were only a few years older than their men.

Often, poorer farm families suffered hardships when a member served in the Junior Reserves. These families had relied on the work of younger boys, with so many adults already in the military. Some tried to get exemptions from service for their sons. The efforts usually did not succeed, as the Confederate government tightened the rules for exemption. As a result, some Junior Reserves deserted and went home to help with the harvest and feed their families.

While in military service, members of the Junior Reserves endured the usual tedium of camp life, drill, and guard duty. Sometimes, they had to march long distances in bad weather. Often they did not have enough to eat and lacked adequate clothing for winter. Many died of diseases such as typhoid fever, pneumonia, and measles.

As North Carolina became a more active battleground in the final months of the war, the Junior Reserves saw combat. They helped defend Fort Fisher, near Wilmington, on December 25, 1864, and fought in the battles of Kinston, or Wyse Fork (March 8–10, 1865), and Bentonville (March 18–21, 1865). In some cases, the Junior Reserves demonstrated an unsteadiness under enemy fire that was not unusual among inexperienced Civil War units. In other clashes, they behaved bravely and won praise from witnesses. Complete casualty figures for the Junior Reserves in these and other fights do not seem to exist, although it is documented that some were killed or wounded.

Unfortunately, not many wartime documents for the Junior Reserves have survived at all, whether in the form of official papers like muster rolls, or in the form of personal diaries or letter collections. It is especially unfortunate that very few wartime writings from members of the Reserves themselves exist. There is more out there from their older officers and commanders, but that is not quite the same thing. Many records simply did not survive the war. Modern historians often are limited by what family members decided to preserve (and donate to archives and other places where they can be studied).

We may find it hard to imagine sending thousands of 17-year-old boys off to war to live for months without adequate food, clothing, and shelter. Yet in the Civil War, numerous teens left their families behind to endure hunger, enemy troops, and other hardships. Many endured much worse besides. Although the North Carolina Junior Reserves did not play a major role in the war, their story remains important in understanding the impact of the conflict on the Tar Heel State.

*At the time of this article’s publication, Michael W. Coffey worked as an assistant editor in the Historical Publications Section of the Office of Archives and History. He is coeditor of the series North Carolina Troops 1861–1865: A Roster and authored the history of the Junior Reserves published in Volume 17 of the series. Coffey received an MA in history from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and a doctorate from the University of Southern Mississippi

Additional Resources:

"N.c. Junior Reserves." N.C. Highway Historical Marker HHH-16, N.C. Office of Archives & History. https://www.ncdcr.gov/about/history/division-historical-resources/nc-highway-historical-marker-program/Markers.aspx?sp=Markers&k=Markers&sv=HHH-16 (accessed October 3, 2013).

Image Credits:

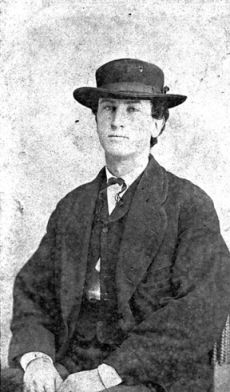

John Daniel Kerr, Sr., of New Hanover County, was elected captain of Company B, Seventh Battalion N.C. Junior Reserves, in June 1864 at age 18, photo by C. M. Van Orsdell, c.late 1860's. Image courtesy of the North Carolina Office of Archives and History, call #: N_95_4_8.

Officers of the Second Regiment North Carolina Junior Reserves (sometimes called the 71st Regiment North Carolina Troops after the war). Image from Volume IV of Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War 1861-’65, edited by Walter Clark (published in 1901 by the State of North Carolina).

1 January 2006 | Coffey, Michael W.