Folklore

See also: Brown Mountain Lights; Conjure; Devil's Horse's Hoofprints; Devil's Tramping Ground; Folk Music; Ghosts; Maco Light; Madstones; Root Doctors; Southern Folklife Collection; Wampus.

Part i: Introduction; Part ii: Types of Folklore and the North Carolina Folklore Society; Part iii: North Carolina Folktales and Storytellers; Part iv: Legends, Animal Tales, and Superstitions; Part v: References

Part III: North Carolina Folktales and Storytellers

Among the primary forms of folk narratives, folktales are medium-length stories traditional among a given group. North Carolina enjoys a rich folktale heritage and a wealth of excellent storytellers. Folktales stretch recollections of everyday occurrences into stories of the supernatural. Passed down through generations of storytellers, these tales often reflect the simple farming lifestyle common throughout North Carolina in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Isolation and lack of formal education in rural communities led to a reliance on natural signs found in the moon, crops, and livestock to explain everyday events such as births, deaths, and marriages. Folktales capture the spiritual omens, rural traditions, and livelihood of a specific region and may act as historical reference for future generations. They relay a moral or lesson by involving an ordinary hero, usually the storyteller, in an extraordinary experience. The story's hero often assumes supernatural strength, accuracy, or cunning to overcome an obstacle or accomplish a goal. The storyteller's sincere and straight-faced rendering of the tale often dictates its success.

Native American folktales include animal stories, creation myths, legends, and ghost stories. Indian storytellers, particularly those of the Cherokee Indians of western North Carolina, continue to play a vital role in the state's rich folklife. Living Stories of the Cherokee (1998), edited by Barbara R. Duncan, contains stories told by Davey Arch, Robert Bushyhead, Edna Chekelelee, Marie Junaluska, Kathi Smith Littlejohn, and Freeman Owle, Cherokee storytellers who learned their art through familial and community traditions.

Some of the best-known North Carolina folktales, and a prime example of the cultural importing so common in the folk tradition, are the Jack tales, comprising a group of sagas from the southern Appalachian Mountains revolving around the lively deeds and delightful adventures of a young boy named Jack. Although one of these tales, "Jack and the Beanstalk," is extremely well known, less familiar are the 17 other surviving stories. As successive generations passed down the tales by word of mouth, Jack acquired a distinctively mountaineer flavor, but two of the tales preserve elements of Norse mythology that indicate the ancient character of these British-American tales.

In 1927 folklorist Isobel Gordon Carter collected the first three Jack tales from Jane Gentry in Wise, Va., and published them in the Journal of American Folk-Lore. Eight years later, folklorist Richard Chase uncovered a dozen more tales as told to him by R. M. Ward and his relatives living near Beech Mountain, N.C. Ultimately, Chase demonstrated that a common ancestor and celebrated storyteller, Council Harmon (1803-96) of Watauga County was the source for all the tales inherited by his Ward and Harmon descendants in North Carolina and his Gentry descendants in Virginia. In the Ward family, the tales functioned practically as a way of entertaining children while they worked at various communal tasks, such as stringing beans. The later discovery of other Jack tales in unrelated families scattered across Appalachia suggests that the tales were once quite common in the region and throughout America. In 1943 Richard Chase edited and published the stories in The Jack Tales, which contains a scholarly appendix by folklorist Herbert Halpert.

Jack tales themselves are often referred to as "tall tales," not because of the giant's scope, but because of their aforementioned ability to expand the bounds of reality and belief. In general, tall tales are folk narratives that stretch recollections of everyday occurrences into stories of the supernatural. Tall tales possess all the major characteristics of folklore and also encapsulate an everlasting image of rural innocence. They relay a moral or lesson through the deeds and commentary of the hero-often the character who provides the audience with the ultimate perspective. All tall tales incorporate elements of the simple life exaggerated to heroic proportions, wherein the simple acts of hunting or fishing might become epic enough to merit timeless status. North Carolina novelist Daniel Wallace, for example, incorporated a strong sense of the southern oral tradition into his sometimes supernatural, folk-infused work Big Fish (1998).

North Carolina folklore is, indeed, a cultural crossroads. The communal mode of story crafting has resulted in numerous combinations of popular myths and beliefs to suit particular social or ethnic groups. While the North Carolina folk tradition owes its diversity, in large part, to combining influences, its native storytellers help to boost its popularity within the state. The North Carolina Storytelling Guild supports the state's storytellers through various programs and events centered on the art of oral tradition. The guild's annual storytelling festival, held each November, attracts North Carolina storytellers as well as many participants from outside the state.

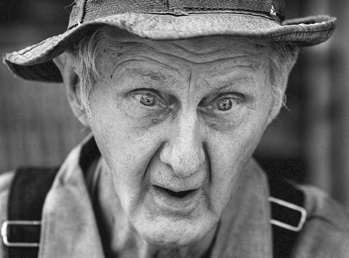

North Carolinian Ray Hicks (1922-2003) is widely considered the "grandfather of storytelling" in the United States. His influence extended beyond his Old Beech Mountain roots, annually taking him to Jonesborough, Tenn., where he was the top-billed personality at the National Storytelling Festival since its establishment in 1973. Hicks was credited with reviving the art of American storytelling in the latter part of the twentieth century, a movement he launched from his home in the North Carolina mountains. He strongly believed in the fantastic in everyday life and idolized his family members for their ability to weave stories out of their everyday experiences. Hicks's stories, of which there are thousands, revolved around him but dealt with his alter-ego "Jack"-a nod to the folklore traditions he so deeply revered. The messages in his tales were down-to-earth, gleaned from a hardscrabble life in the mountains living in the house in which he was born.

In a technological age, Hicks insisted on living in his ancestral home, telling his ancestral tales, and acting as a living encyclopedia of natural mountain knowledge. American oral traditions are largely indebted to him-not only for his contributions, but for the profile he set among North Carolinians and storytellers nationwide.

Keep reading > Part IV: Legends, Animal Tales, and Superstitions![]()

1 January 2006 | Baker, Bruce E.; McFee, Philip