Church of England

See also: Episcopal Church; St. Thomas Episcopal Church; Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts.

The Church of England, or the Anglican Church, arrived in North Carolina with the initial colonists venturing to Roanoke Island under Sir Walter Raleigh. In 1585 Manteo, a Native American, and Virginia Dare, the first English child born in America, were baptized, indicating the presence of an Anglican priest. The Carolina charter of 1663 permitted religious toleration of other Protestant groups but provided for the establishment of parishes of the Church of England in the colony. However, the Church of England neither supplied clergymen nor began to build churches until the eighteenth century. The sparse organized religion of seventeenth-century North Carolina was provided by the Quakers.

The Church of England, or the Anglican Church, arrived in North Carolina with the initial colonists venturing to Roanoke Island under Sir Walter Raleigh. In 1585 Manteo, a Native American, and Virginia Dare, the first English child born in America, were baptized, indicating the presence of an Anglican priest. The Carolina charter of 1663 permitted religious toleration of other Protestant groups but provided for the establishment of parishes of the Church of England in the colony. However, the Church of England neither supplied clergymen nor began to build churches until the eighteenth century. The sparse organized religion of seventeenth-century North Carolina was provided by the Quakers.

In 1701 the Assembly passed the first Vestry Act, which divided the colony into five parishes. Each parish had a vestry of 12 men, who elected 2 of their members as wardens. The vestries were supposed to start building churches, care for widows and orphans, and levy a tax on property owners to provide funding for the church.

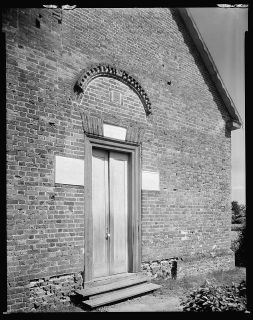

In December 1701 the nucleus of St. Paul's vestry met at the home of Thomas Gilliam, near what later became Edenton, and soon began to build a church on an acre of land donated by Edward Smithwick. This church, the first one in North Carolina, was "very sorrily put together." Ten years after work began, cattle and swine continually wandered into the building, which had neither a floor nor a lock. The first substantial Anglican church in the colony was St. Thomas's in Bath, begun in 1734, followed by St. Paul's in Edenton, begun in 1736. Both buildings remain standing as popular historic sites.

Even with a succession of other Vestry Acts, church growth was slow. There was no Anglican bishop in America. Few clergymen were appointed for North Carolina, and of those selected, many were unfit for or dissatisfied with their posts. The first Anglican clergyman in the colony, Daniel Brett, was one of several reputed to indulge in immoral behavior. Another early missionary, John Blair, became disgusted with the colony-"the most barbarous place on the continent"-before he quit, and Governor Arthur Dobbs, an ardent church advocate, despaired of the "deluded depraved colony." Some Anglican priests in North Carolina were accused of wholly ungodly behavior, such as stealing, public drunkenness, and adultery.

By 1765 only 5 Anglican Church buildings existed in North Carolina. Of these, only the New Bern church was "in good repair"; those in Brunswick and Wilmington were unfinished, and those in Bath and Edenton were in need of repair. Most parishes either had no building at all or only a small chapel served by lay readers and occasionally visited by traveling missionaries or ministers from distant towns. The Reverend Alexander Stewart not only supervised the construction of St. Thomas's Church in Bath but also preached at 13 chapels in Beaufort, Pitt, and Hyde Counties. One minister complained that the "chapels" in his parish were merely "people's houses where we are obliged to attend." Another chapel was "a most miserable old house . . . [where] ev'ry shower of Rain or blast of wind blows quite through it."

The Church of England in North Carolina received only limited financial support from England and from the government of the colony. Many so-called dissenters-Quakers, Baptists, Moravians, Presbyterians, Lutherans, and others-objected to compulsory taxation to fund an "established church" to which they did not belong. Before 1751 vestrymen were appointed by the Assembly; afterward, they were elected by the freeholders of each parish. Vestrymen were not required to be members of the Church of England.

Despite many obstacles, the Church of England accomplished much good in the North Carolina colony. Vestries helped support widows and orphans and arranged apprenticeships for needy children. The church helped establish some of the few schools in the colony, including the one opened by Charles Griffin in Pasquotank County in 1705, the first recorded school in North Carolina. Stewart dedicated much of his time to the conversion and education of the Indians of eastern North Carolina. Some Anglican clergymen preached to the enslaved people in the colony, although their early efforts were thwarted by the false belief among enslaving planters that baptism meant emancipation. Missionary efforts in the antebellum period were also hampered by the scarcity of clergy and the resistance of many enslavers to any education or religious training of their owned enslaved people.

Never overly vigorous in North Carolina, the Church of England lagged behind other, more popular denominations by the time of the American Revolution. The North Carolina Constitution of 1776 stated that no state church would be established and that church attendance and payments would be voluntary. The Church of England's ties with the royal government caused it to fall from favor after the Revolution. Following the departure of many Anglican clergymen and church members, the church nearly disappeared in North Carolina. It was not until 1817 that the former Church of England, now known in the United States as the Episcopal Church, established a diocese in North Carolina and began to develop the modern church, which includes several congregations that refer to themselves as "Anglican."

References:

Lawrence F. Brewster, A Short History of the Diocese of East Carolina, 1883-1972, with Its Background in the Heritage of the Anglican Church in the Colony and the Protestant Episcopal Church in North Carolina (1975).

Lawrence Foushee London and Sarah McCulloh Lemmon, The Episcopal Church in North Carolina, 1701-1959 (1987).

Alice E. Matthews, Society in Revolutionary North Carolina (1976).

Alan D. Watson, Society in Colonial North Carolina (1975).

Image Credit:

"St. Thomas' Church, Bath, Beaufort County, North Carolina." Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C., reproduction #: LC-DIG-csas-02184. Available from http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/csas.02184/ (accessed June 6, 2012).

1 January 2006 | Norris, David A.