The federal judicial system was created with the opening words of Article III of the U.S. Constitution: "The Judicial Power of the United States shall be vested." The framers of the Constitution desired a system of national courts to effectively implement the powers of the national government, as they feared that state courts might not fully enforce federal policies, especially if federal and state interests conflicted. Moreover, federal courts were viewed as important to protect individual liberties. Reacting to these concerns, Congress, through the Judiciary Act of 1789, established lower federal courts in 11 of the original 13 states. A national Supreme Court already had been created directly by Article III.

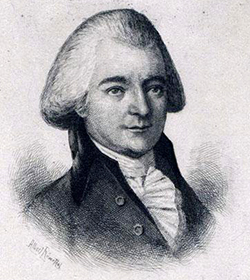

Early attempts to hold the lower federal courts contemplated by Article III led to a series of mishaps in North Carolina. A convention meeting at Fayetteville ratified the Constitution in November 1789, too late for the state to be included in the organization of the young nation's first federal courts created by the Judiciary Act passed earlier that year. Efforts to fix the location of federal tribunals in North Carolina were not completed until 4 June 1790, when Hugh Williamson, who represented Edenton and New Bern in Congress, shepherded through both houses a bill stating that all courts would meet in New Bern. William Richardson Davie, Revolutionary War hero and a founder of the University of North Carolina, was President George Washington's first choice for the post of federal district court judge of North Carolina. On 8 June 1790 the Senate confirmed the appointment, but Davie later declined it. Washington then nominated John Stokes of Rowan County, but within two months Stokes was dead, never having mounted the bench. Washington and his successor, John Adams, enjoyed greater success in naming North Carolinians to seats on the U.S. Supreme Court. James Iredell (1790-99) and Alfred Moore (1799-1804), both staunch Federalists, remained as of 2006 the only North Carolinians ever appointed to the Supreme Court.

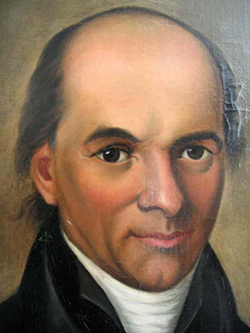

The federal courts in North Carolina achieved a surer footing with Washington's appointment of John Sitgreaves, a New Bern attorney, to the district court bench on 17 Dec. 1790. Sitgreaves served as the state's federal district judge for 12 years, holding courts in New Bern, Wilmington, and Edenton until his death in 1802. Twice each year, in tandem with a Supreme Court justice, Sitgreaves held the U.S. Circuit Court for the District of North Carolina, first at New Bern and later in Raleigh after the government relocated there. The numerous differences between the respective jurisdictions of the district and circuit courts were set forth in the provisions of the Judiciary Act of 1789, though the subject matter jurisdiction of all federal courts was extremely narrow throughout the nineteenth century. Most of the caseload in North Carolina involved concerns of the admiralty, a small group of federal crimes, and, from 1790 to 1810, claims by British citizens for restoration of property lost or seized during the Revolution. Perhaps as a result of North Carolina's moribund commercial life, none of the important decisions by Chief Justice John Marshall interpreting the Commerce clause of the Constitution emanated from local federal courts.

The most significant case brought before the North Carolina federal circuit court was Granville's Devisee v. Allen, a Revolutionary War reparations action heard in 1805. Although most of North Carolina's colonial Lords Proprietors had ceded their landholdings in the New World to the Crown half a century before shots were fired at Lexington and Concord, Earl Granville retained the right to dispose of property in a vast region known as the "Granville District." Occupying much of the northern third of the colony, the Granville District was teeming with settlers and land speculators soon after the 1777 General Assembly enacted statutes vesting title to the whole district in the state. Three decades later, Earl Granville's heirs brought a test case seeking to eject substantial planters William R. Davie (whom Washington had sought to make a federal judge) and Josiah Collins, and by extension, thousands of other settlers, from the land. Chief Justice John Marshall, who in 1805 had been leading the U.S. Supreme Court for four years, was to preside over the circuit court along with federal district judge Henry Potter. On the ground that he had served as counsel and had had a financial interest in a similar Virginia case, Marshall recused himself from the case. Left to hear and decide the dispute on his own, Potter ruled that the defendants could keep their land. Highly popular with the public, this decision may have stanched the flow of North Carolinians migrating to other states as a result of the Granville heirs' claim.

When North Carolina seceded from the Union in 1861, Potter's successor, Asa Biggs, resigned as district judge. No federal court was held in the state for the duration of the Civil War. After Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox, Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase declined to come to Raleigh to open the U.S. Circuit Court, maintaining that it was inappropriate for a member of the Supreme Court to exercise civil authority in a state still under military occupation. Nevertheless, the first session of the circuit court to be held in the former Confederacy opened in Raleigh in June 1867. Even after North Carolina was readmitted to the Union, federal judges performed their official duties among a resentful and politically hostile people.

By an act of Congress dated 4 June 1872, taken in recognition of the precipitous growth of the state's western counties, North Carolina was divided into two federal judicial districts: the Eastern District and the Western District. In another important structural development, Congress in 1891 created a layer of intermediate appellate courts to relieve the Supreme Court of the duty of considering all appeals in cases originally decided by the federal district courts. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, by which the federal appeals court with jurisdiction over North Carolina came to be known, originally was supplied with three permanent circuit judges.

Although North Carolina was long the largest state in the circuit (which embraces Virginia, Maryland, West Virginia, and the Carolinas), only six North Carolinians have served as judges in the Fourth Circuit. These six, however, have exerted remarkable influence over the course of the court's jurisprudence. Jeter C. Pritchard, appointed to the court in 1904, served until his death in 1921. John Johnston Parker Jr., named to the Fourth Circuit in 1925 by President Calvin Coolidge, quickly garnered praise as one of the most admired federal judges in the country. Although the Senate failed to confirm Parker's nomination to the Supreme Court by President Herbert Hoover in 1930, Parker continued to serve as the Fourth Circuit's chief judge until his death in 1958. His successors, Jesse Spencer Bell (1961-67), James Braxton Craven Jr. (1966-77), James Dickson Phillips Jr. (1978-94), and Samuel James Ervin III (1980-99), are numbered among the Fourth Circuit's most influential judges. Ervin, who became chief judge in 1989 and served until his death in 1999, was the second North Carolinian to lead the Fourth Circuit after Parker.

In 1927 Congress further subdivided North Carolina into three federal districts, carving counties out of the old Eastern and Western Districts to form a new Middle District. Congress also recognized the growing federal caseload in the state by adding judgeships to each district. Beginning in 1994, four active district judges held court in the Eastern and Middle Districts; in the Western District, three presided. Each district also had at least one judge of senior, or semiretired, status who held court according to his inclinations. Counting the state's 2 sitting circuit judges, 2 prospective circuit court appointments, and 15 active and senior district judges, the Article III federal bench sitting in North Carolina numbered nearly 20. In addition, within each judicial district, groups of federal magistrate judges and bankruptcy judges assisted the district judges with decision-making duties in certain statutorily defined categories of cases. Considered as a whole, the federal judicial system in North Carolina by the early 2000s had grown thirtyfold since its creation in 1790.