North Carolina generally welcomed Thomas Jefferson’s contested election as president on the Democratic-Republican ticket in 1800. Its citizens applauded his celebration of the yeoman farmer and his embrace of limited government. The Federalist minority that survived through Jefferson’s presidency and into the administration of his hand-picked successor and fellow Virginian, James Madison, would never seriously threaten the Republican ascendency. Yet when the Federalists collapsed entirely after the War of 1812, the Republican Party, deprived of its old adversary, quickly disintegrated as well. Meanwhile, slavery spread, along with evangelical religion, but, in the Old North State, political reform came slowly.

Eli Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin in 1793 made large-scale cotton production economical and created a new demand for slaves. Slaveholdings in North Carolina tended to be small; few whites could afford more than one or two slaves. Some religious groups, chiefly the Quakers, and some ethnic groups, especially the Germans, tended to avoid slave ownership entirely. Still, if only a minority of whites owned slaves, most African Americans were slaves. Slaves as a percentage of the population increased after 1800, and slave-owners dominated state politics.

Evangelical Christianity, too, became more entrenched in the state. The state’s feeble Anglican Church declined after the American Revolution, but newer evangelical denominations that stressed salvation by sudden emotional conversions, as opposed to a lifetime of good works, grew rapidly. Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians appealed to women, slaves, the less affluent, and the less established. The renewal of religion peaked with the Great Revival (or Second Great Awakening) of 1801 to 1805, which began with the famous Cane Ridge, Kentucky camp meeting. In October 1801, the revival reached North Carolina with a five-day camp meeting at Hawfields Presbyterian Church in what is today Alamance County. Stressing personal piety over social justice, the new churches left rural life more sedate, with less card playing, drinking, and gambling while otherwise leaving the political order undisturbed.

Depending on the issue, the state’s political battles split voters along sectional lines, with easterners fighting westerners, or along the familiar partisan divide between Republicans and Federalists. The parties feuded, for instance, over control of the University of North Carolina. Republicans hoped it would promote democratic values; Federalists feared it would encourage religious skepticism. They disagreed over banking policy, with Federalists supporting privately owned banks, and Republicans preferring a state-managed bank. Republicans supported the creation of new courts. Federalists opposed them; they took legal business from older towns where Federalists were strong. More courts also meant more travel for lawyers, who tended to be Federalists.

Controversy over an 1811 election law overshadowed Congress’s declaration of war against Great Britain in 1812. In an effort to ensure that the Republican presidential ticket got North Carolina’s entire electoral vote, the law allowed the assembly to select electors. The measure proved so unpopular that most of the members who had supported it did not return for the next session. The assembly repealed it after the 1812 election.

The War of 1812 failed to unite Tar Heels. North Carolinians supported the Madison administration’s foreign policy without showing great enthusiasm for the war, and few rose to prominence during the conflict. Former governor David Stone resigned his Senate seat because his opposition to the war offended many of his constituents. The popular First Lady Dolley Madison was a Guilford County native, although she grew up in Virginia. Andrew Jackson, hero of the Battle of New Orleans, was born along the North Carolina-South Carolina border; both states claimed him. Less famous figures had firmer ties to the state. Otway Burns of Onslow County was a successful privateer. Captain Johnston Blakely of the United States Navy terrorized British shipping before disappearing at sea on a voyage home from a raid in the British Isles. Complaints that the federal government had neglected the state’s defenses seemed validated on July 11, 1813, when a British fleet under Admiral George Cockburn appeared at the entrance of Pamlico Sound. The British landed at Ocracoke and Portsmouth, captured two privateers, seized livestock, and sailed away on July 17. Despite the raid, little hard fighting took place on North Carolina soil.

In much of the United States the end of the War of 1812 witnessed a surge of nationalism and ushered in a period of rapid growth and social change. In North Carolina, by contrast, most whites seemed content with familiar patterns of life on small farms largely isolated from the broader economy. Contentment led to relative, if not actual, decline. North Carolina became known as the “Rip Van Winkle State,” after the character in Washington Irving’s story who slept while the world passed him by.

Education in particular suffered, with predictable results. The legislature responded to the constitutional mandate to provide schools for its citizens by chartering private academies, but when it came to funding, the institutions were left to fend for themselves. No North Carolina assembly in the first quarter of the nineteenth century provided meaningful financial aid to public education. Most counties eventually got an academy, but few of them served girls or reached into remote rural areas. As a result, one-third of the state’s whites were illiterate. Blacks enjoyed virtually no educational opportunities.

Many residents abandoned the state. One contemporary estimated that by 1815, some 200,000 natives had gone west. It is likely that, in the ante-bellum period, almost one-third of the people born in the state moved away. High birthrates prevented an absolute decline in population, but growth slowed. Land values declined and state revenues, which came from property taxes and poll taxes, could scarcely meet the modest demands of the small state government.

The constitution of 1776 had allocated seats in the state legislature by county, not by population. With most of the state’s counties, the east had a majority of the seats, and because, according to the 1790 census, 62 percent of the state’s people lived east of Wake County, that apportionment seemed fair. Yet in the next fifty years, the west grew three times as fast as the east, and the General Assembly became badly misapportioned. By the early 1800s, a minority of white voters elected a majority of assembly members. Not only undemocratic, the assembly became a barrier to reform. Large slave-owners in the east benefited from the status quo and did not want to surrender political power. Able as they were to afford private tutors, they saw no need for public schools and feared heavier taxes on their land and slaves.

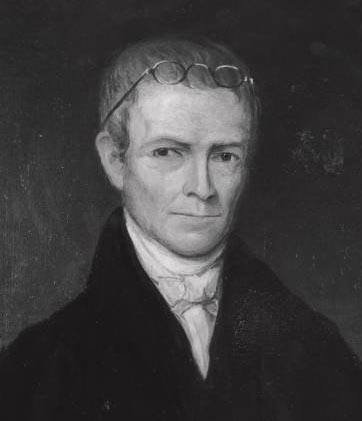

A few North Carolinians pushed for reform, none more persistently than Archibald DeBow Murphey, a lawyer and judge who represented Orange County in the state senate from 1812 to 1818. Legislators had ignored pleas from governors to establish a public school system for years, but in 1815 both houses of the assembly created committees on education. The following year, Murphey submitted a report on behalf of the senate committee. He argued that the state ought to provide schools, with separate grades, for all children. The senate approved the report, but took no further action. In 1817, Murphey submitted a more elaborate plan calling for primary and high schools, schools for the deaf, and a curriculum based on European models. He envisioned a school system supported jointly by local and state funds, with a state board of education supervising the entire system.

Progress came at a glacial pace. Not until 1825 did the assembly take steps to finance a school system, creating a Literary Fund, the income from which would be used to support education. The endowment would be funded by dividends from state-held bank stock, from a tax on liquor sales, and from the sale of state-owned swampland. The scheme proved ineffective as lawmakers raided the fund for other projects while state officials, including state treasurer John Haywood, embezzled money from the school accounts. A state-supported public school would not open its doors in North Carolina until January 1840.

Murphey also argued, in a series of reports issued between 1815 and 1819, for state support of roads and navigation projects, or in the language of the day, internal improvements. The advent of the steam engine helped stimulate interest in transportation, and by the 1820s, steamboats were serving New Bern, Elizabeth City, Edenton, Plymouth, Wilmington, and Fayetteville. Reformers saw improvements in transportation as essential to economic development; farmers would not move beyond subsistence agriculture if they could not find an economical way to get their crops to market.

In 1817, the General Assembly appointed a commission on internal improvements, but the lack of qualified engineers in the state delayed its work. The commission eventually hired an English engineer, Hamilton Fulton, but his 1,200 pounds annual salary—in gold no less—sparked a distracting controversy. The legislature created a special fund for internal improvements, which met the same fate as the Literary Fund. The money it was promised never fully materialized and much of what it got was stolen by the state treasurer. The fund could never support more than a few small projects.

Internal improvements stalled in part because the east controlled the assembly, while demands for schools, roads, and canals came mainly from the west. In 1816, Murphey had issued yet another report, this one calling for constitutional reform and complaining that “about one third of the White Population elect a Majority of the Members of the General Assembly.” Conservatives, however, blocked efforts to submit his proposal for a constitutional convention to a popular referendum. Nathanial Macon, the dean of the state’s congressional delegation, spoke for many when he opposed reform in part because of fears it could lead to the abolition of slavery. “This new way,” as he called the popular obsession with progress, “…leads to universal emancipation.” Ironically, as the historian Harry Watson has noted, Murphey’s efforts to connect North Carolina to national and international markets would actually strengthen its commitment to the slave labor that produced its most valuable exports.

As the Republican ascendancy came to an end, North Carolina experienced the first flickering of a political realignment that would lead to a constitutional convention in 1835 and a new era of reform. With the demise of the Federalists, Jefferson’s Republican Party, long plagued by its own divisions, broke apart. In 1824, the Republican caucus in Congress, which normally selected the party’s ticket, nominated William Crawford of Georgia for president, while dissident Republicans in the west supported Andrew Jackson. The House of Representatives eventually resolved a bitterly disputed election in favor of another Republican, John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts. In 1828, in a two-candidate race between Adams and Jackson, North Carolinians generally fell in line behind Jackson, but his opposition as president to a national bank and to federal aid for internal improvements disappointed westerners and led to the creation of a new Whig Party that would, in North Carolina, become a successful champion of reform.