Established: 1974 (natural Area); 2008 (State Park)

GPS Coordinates: 36.505700,-76.355100

Size: 14,344 acres

See also: Exploring North Carolina: North Carolina State Parks, Trails, Lakes, Rivers & Natural Areas

Park Area History

Early European settlers encountered a very different Great Dismal Swamp than the one we see today. In the late 1600s, the Dismal was a vast wetland, covering about 1.28 million acres. It stretched from the James River in Virginia to the Albemarle Sound in North Carolina. For centuries, Native Americans used the Swamp as hunting and fishing grounds but found it too wet to make homes there.

Some early explorers, such as William Byrd II, saw no value in swampland and thought it should be drained and converted to agricultural uses. The system of ditches criss-crossing Dismal was intended to carry water out, but this endeavor was only partially successful. Although the water table dropped significantly, the Swamp remained unsuitable as farmland, and so efforts then turned to harvesting timber. Cypress and cedar both could be used to make durable products with exceptional resistance to moisture. Cedar shingles were a very common product of the Swamp in the 1800s. By the 1880s, most hardwood trees had been logged out, but commercial logging continued into the 1960s.

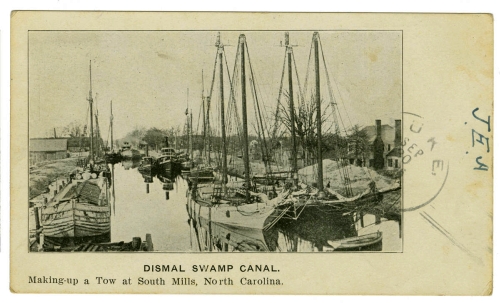

The Dismal Swamp Canal itself represents an important piece of American history. While the idea of a canal originated in the early 1700s, construction did not begin until 1793. Dug almost entirely by slaves, the Canal stretches 22 miles, from Deep Creek in Chesapeake, VA, to the town of South Mills, NC. The slaves forced to dig the channel by hand faced terrible working conditions: waist-deep muck and peat, extreme summer heat, biting insects, and venomous snakes. On average, they were able to complete about 10 feet of the Canal each day, while their masters collected their wages for the work. In 1805, 12 years later, the Canal opened to boat traffic, but it was so narrow and shallow that only flat-bottomed barges called lighter boats or gondolas were able to traverse it. These lighter boats, however, were used extensively to move timber products out of the Swamp and off to market. You can see a replica lighter boat exhibit along Canal Road, about 0.7 miles from the Visitor Center.

The Dismal Swamp Canal changed private hands several times and fell into disrepair during the Civil War, while the Union and the Confederacy each fought to control this vital means of transporting supplies. Finally, in 1929, the United States government purchased the Canal for $500,000 and the Army Corps of Engineers widened and dredged it to its current width of about 50 feet and depth of about 9-12 feet.

At different times in its past, the Dismal Swamp has been viewed as a “glorious paradise,” a grim and foreboding place of strange smells and sounds, and a refuge. Lawbreakers found it an ideal place to hide illegal moonshine stills during the Prohibition years. Today, you can see a replica still along Canal Road about a half mile from the Visitor Center and the remains of real stills along the Supple-jack Trail.

In the time of slavery, many runaway slaves bravely seeking a path to freedom took shelter in the Swamp. Some stayed only briefly to rest before finding passage farther north, but some formed maroon colonies on mezic islands, areas of higher ground, and lived out the rest of their lives in the Swamp. Researchers believe the Dismal may have been home to the largest maroon colony. In December 2003, the National Park Service recognized the Great Dismal Swamp as a site on the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom. It is the only such site to span two states (Virginia and North Carolina).

Park History

In 1972, the Nature Conservancy purchased land from timber companies and sold over 14,000 acres of that land to the State of North Carolina in 1974. For many years, the area was managed as the Dismal Swamp State Natural Area. Landlocked on three sides and bordered by the Canalon the fourth, access for the general public was limited. Following construction of the $1 million unique hydraulic swing bridge over the Canal and the Visitor Center, the Dismal Swamp State Park opened in 2008.

Park Ecology

The park protects 22 square miles of forested wetland in the Great Dismal Swamp, the largest remaining swamp in the eastern United States. Historically, the swamp was much wetter than what you see today. Extensive ditching and logging have changed its character over the past 200 years. Today's Dismal is dominated by red maple in place of the bald cypress and tupelos that once flourished here. But make no mistake; the Dismal Swamp is still an area of great natural significance.

Populations of Atlantic White Cedar can be found along the western edge of the park. The cedar trees grow in deep peat soils common to the area. Hessel's Hairstreak, a rare butterfly species dependent on the white cedar, has been seen here. Black-throated green warblers may be found nesting among these conifers.

Only a few old logging roads and ditches break the vast forests of the park. The roadbeds serve as park trails and form habitat used by a wide variety of wildlife that live in the forests. Bobwhite and turkey are often seen feeding on seeds and insects here. Deer and marsh rabbits browse on the green herbs that thrive in the sunlight.

Blackberry brambles and devil's-walking-stick are abundant along the roadsides. The fruits of these plants are favorite foods of the numerous black bears that live in the swamp. Persimmon, poke, blueberry, various oaks, black walnut and tall pawpaw also provide food for wildlife. Tracks of raccoons, opossums, and gray fox can be seen along the roads. Bobcats roam these open areas in search of prey.

Butterflies abound in the Dismal. Forty-three species have been identified in the park so far. Huge numbers of Palamedes and zebra swallowtails can be found 'puddling' along the roads during certain times of the year. Tiger swallowtails, Atlantic holly azures, and variegated fritillaries are also present in large numbers.

Along the forest edge supple-jack, grape, and greenbrier create dense tangles of vines. Neotropical songbirds such as the American redstart and the black-and-white warbler find these conditions perfect for nesting. Yellow-throated warblers and white-eyed vireos are often heard among the vines, but can be difficult to see. Swainson's warblers are known to nest within the swamp, but they are rarely seen. Prothonotary warblers and wood ducks can be spotted along the ditches that parallel the roadbeds. Seven species of woodpeckers are present in the park. Red-shouldered hawks can often be seen flying through the forest. Occasionally barred owls can be heard calling from deep in the swamp.

The high pocosin along the northern boundary of the park is dominated by dense stands of inkberry. Gallberry, shining fetterbush, and sweet pepperbush are also found here. High pocosin is a fire-dependent natural community. It is becoming rare in the Dismal today.