Dentistry, like medicine, has changed dramatically throughout history. From colonial times through the first decades of the nineteenth century, dental procedures were merely an additional service offered by men in the barber trade or occasionally by an individual with some medical education. Parents usually played the role of "dentist" for their children, pulling out decayed teeth with a variety of crude methods. In North Carolina no formal dental training was available, and consequently there was no way of gauging who was qualified to perform dental surgery. A New Bern shoemaker named E. R. Hubbard, for example, was purported to have occasionally abandoned his cobbler's bench to work on the sore tooth of a complaining customer.

Some early North Carolinians actually called themselves dentists, took their work seriously, and maintained successful practices that often led them from region to region in search of patients. The Hillsborough Recorder of 22 Aug. 1821 carried an advertisement by a Mr. Hurley, who "operated for all illnesses of teeth and gums, freed the teeth from tartar, filled and plugged decayed teeth, straightened children's teeth, and inserted artificial teeth after the most approved manner and in a style so nearly approaching nature as to bid defiance from detection." Clearly, some form of dental standards had begun to take shape.

In 1835 approximately 15 dentists practiced statewide, and probably countless others occasionally performed dental procedures. Five years later, in 1840, the world's first dental school opened in Baltimore, Md., and schools soon followed in Ohio, Massachusetts, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. W. R. Scott, of Raleigh, who received a degree from the Baltimore College of Dental Surgery in 1842, became the first North Carolinian to graduate from a school of dentistry and practice in the state. As educational opportunities grew, a broader range of people chose to become dentists, and dentistry evolved from a trade into a profession. The dental community created a system of standards and ethics to safeguard its professional gains and ensure that patients received the best care possible.

Disruptions caused by the Civil War led to the temporary dissolution of the Dental Society. Officially reorganized in 1875 with approximately 200 active members, it began to lobby the General Assembly to bar anyone without a degree from an accredited dental college from practicing in the state. In 1879, after much political wrangling, the legislature passed a law mandating that all future dentists either be graduates of a dental school or prove their competency to the newly established Board of Dental Examiners. The law was amended in 1905 to direct that an individual could not take the state examinations without having first been graduated from a dental school.

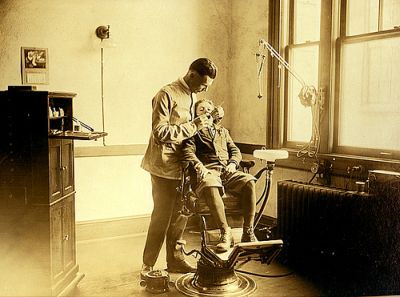

The dental profession in North Carolina continued to expand and change throughout the early twentieth century. Cities such as Asheville, Winston-Salem, and Raleigh formed their own local dental societies. With the increase of high-quality instruments and medicines, procedures became less and less barbaric. Before this time, a painless extraction was all but impossible. Fillings made of gold and tin were put into place by chisel and mallet. Anesthesia and sterilization procedures for instruments were not yet perfected. In the early decades of the twentieth century, new advances in preventive dentistry led to a revolution in dental care. The focus shifted from merely pulling and filling teeth and making crude dentures to informing patients about oral hygiene and keeping their teeth healthy and strong.

In 1918 North Carolina was the first state in the nation to found a statewide dental health program under the auspices of the State Board of Health. During this period, support for the establishment of a dental school in the state began to grow. In 1947 Claude M. Parks, president of the Forsyth County Dental Society, led a committee researching the need for such a school. Facts gathered were alarming: North Carolina ranked a lowly 45th in the nation in dental care, with 1 dentist for every 3,778 citizens; an estimated 42 new dentists every year would be needed even for this low ratio to be maintained. Many North Carolinians who desired to practice dentistry were unable to get into the crowded out-of-state schools or did not return to the state after graduation.

The Forsyth County Dental Society proposed the idea of an in-state dental school to the North Carolina Dental Society, which successfully lobbied the state legislature for funds in 1949. By 1950 dental students at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill were studying in Quonset huts while the school was under construction, and in 1954 the first class of 34 students was graduated. The creation of a dental school and subsequent increases in class size did not eliminate the shortage of dentists in the state, however, as the dentist-population ratio continued to hover near the nation's lowest. The situation was worsened by the fact that many dentists preferred to practice in urban areas, leaving many rural regions gravely underserved.

During the last decades of the twentieth century, the dental profession in North Carolina made great strides in educating the citizenry about the importance of dental hygiene. During the 1970s the state initiated pilot programs in several counties to take this message to the public schools, creating manuals for teachers as well as students. New decay-fighting substances and procedures, the fluoridation of water supplies, and a myriad of technical advances-some preventive and others aesthetic-led to greater dental health in populations served by sufficient dental personnel.

Overall, statistics relating to dental health in North Carolina have remained steady. By the early 2000s there were approximately 3,400 dentists and 4,000 dental hygienists, representing a dentist-population ratio of about 1:2,470. Four counties-Jones, Tyrrell, Camden, and Hyde-had no practicing dentists, and Bertie, Currituck, and Gates Counties had only one each. The counties with the most dentists were Mecklenburg (453), Wake (433), Guilford (231), and Forsyth (176). Children's dental health was monitored and enhanced by the Oral Health Section of the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services.