Country clubs became a part of American life during the last quarter of the nineteenth century with the rise in popularity of golf. Having evolved from city clubs with the influence of resort hotels, hunt clubs, and spas, country clubs, first found in the Northeast, offered their members private social, dining, and outdoor recreational facilities. Although golf clubs appeared more slowly in the South than in the Northeast and Midwest, the original Asheville Country Club golf course may have existed as early as 1893, which would make it the state's first country club and golf course.

Dates for the opening of facilities are far easier to obtain than for the actual founding of the clubs as legal entities. Newly formed clubs issued bonds to their members in order to raise capital to purchase land and build facilities. Although an extant account book demonstrates that the Chapel Hill Country Club existed by 1907 and had purchased golf equipment before 1919, their nine-hole course southeast of the University of North Carolina campus apparently did not open until 1923. Other early North Carolina country club golf courses included Raleigh's Carolina Country Club (1912), Greensboro Country Club (1911), and Forsyth Country Club (1911) in Winston-Salem. In Pinehurst, the Tufts family from Massachusetts developed full-service winter resort facilities, including golf after 1897. It eventually combined a membership country club (currently based on where one lives within the Village of Pinehurst) with a commercial resort.

Country clubs sprang up rapidly during the 1920s, as the middle class desired a way to pool resources to enjoy the affluent lifestyle communally. Charlotte built three country club courses and Asheville and Greensboro two each during the decade, while Rocky Mount (1922) and Salisbury (1927) each welcomed one. When Hope Valley Country Club opened in Durham in 1926, George Watts Hill donated the nine-hole Durham Country Club course to the city for what would become the municipal Hillandale Golf Club. Even smaller, more rural towns gained country clubs during this era, including Morganton (1928), Mount Airy (1928), Roanoke Rapids (1923), and Blowing Rock (1922). Barely in North Carolina, Alleghany County's Roaring Gap Club (1926) features a secluded Donald Ross course 3,700 feet above sea level along the edge of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

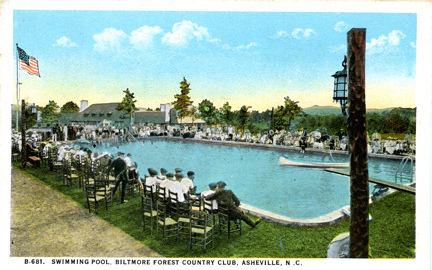

Roughly one country club in seven went under between 1929 and 1939 as a result of the Great Depression, and countless new and expansion clubhouse and golf course projects were canceled. Even the survivors experienced hard times, resorting to membership discounts, benefit dances, and other money makers. By the 1950s, as the polio threat subsided and desegregation came to public facilities, pools became as much a staple of the clubs as golf and tennis facilities. Eventually, country clubs sorted themselves into three broad types: fully private clubs open only to members and their guests; semiprivate clubs that permitted some use of the golf or swimming facilities by nonmembers for a daily fee; and those such as Pinehurst or Linville that afforded privileges to guests of specific resort properties in addition to their member.

Country clubs have served as a means of establishing status and separating members from the larger community, often for reasons based on race discrimination. Whereas Jewish patrons had been allowed to join city clubs, most country clubs generally excluded them. Racist, classist, and nativist impulses have undeniably attracted some to private clubs populated solely by "people like us." Barriers to African Americans remained common among country clubs throughout the United States until 1990, when the Shoal Creek (Alabama) affair generated sufficient public pressure to force the governing bodies of both professional and amateur golf to denounce such practices. Many country club rules also excluded women from joining or playing golf at various "heavy traffic" times, such as Saturdays and Sundays.

A group of African Americans in Greensboro organized Forest Lake Country Club during the late 1950s, although it apparently did not offer golf. Opened for golf during the crest of the civil rights movement in 1965, Garner's semiprivate Meadowbrook Country Club became the first country club for blacks south of Maryland. Businessmen M. Grant Batey, James J. Samson Jr., and Paul Jervay founded Meadowbrook in 1958 by purchasing 140 acres of tobacco land. For many years a fully private club with 150 members, Meadowbrook eventually became semiprivate due to financial pressures. In 1960 Charlie Sifford, born in a racially mixed Charlotte neighborhood in 1922, broke the color barrier on the PGA tour after the courts overturned the organization's "Caucasian only" clause.

The boom years between the end of World War II and 1970 brought even further expansion of country clubs in North Carolina than during the 1920s. Twenty new country clubs appeared between 1945 and 1952 alone. Cities added second private clubs, including Raleigh Country Club (1948), Wilmington's Pine Valley (1956), and Willowhaven (1957) near Durham. Smaller communities established their first country clubs, such as Reidsville (1945), Burlington (1946), Washington (1949), Siler City (1954), Wilkesboro (1958), and Robersonville (1965). In 1963 the original 40 members of the Country Club of North Carolina in Southern Pines contained an assortment of the state's elites. Joining members included businessmen J. Gregory Poole and Karl Hudson Jr. and Democratic politicians Richardson Preyer, Voit Gilmore, and Kenneth Royall, as well as Hargrove "Skipper" Bowles.

During the last decades of the twentieth century, both golf courses and country clubs became linked to real estate developments. Some communities-frequently gated ones such as Carolina Trace (1968), south of Sanford; Bald Head Island (1975); Treyburn (1988), north of Durham; and Governors Club (1989), south of Chapel Hill-used exclusive country clubs with marquee golf course architects (Robert Trent Jones, George Cobb, Tom Fazio, and Jack Nicklaus, respectively) to attract residents to high-end developments.

By the end of the twentieth century, however, country clubs accounted for less than 10 percent of new golf course construction. Elitism and discriminatory practices caused many North Carolinians to take a dim view of country clubs. Citizens of Boone rejected the idea of a country club as inappropriate for their community in 1957. The Carolinas Golf Association reported in 1999 that while the number of courses had increased 20 percent during the previous decade, the number of country club courses had decreased 13 percent. Economic and social changes, along with the development of high-end daily fee courses that promised better golf than the private clubs, took their toll on country clubs. Some changed to semiprivate status or accepted more outside play through tournaments and privilege cards. Others turned to real estate tie-ins and aggressive membership campaigns.

While these factors greatly increased access by nonwhites, they also signaled problems for the country club as an institution by the early 2000s. As new country clubs became arms of real estate ventures, the private courses continued to decrease in relative significance as venues for golf. Meanwhile, private clubs similarly lost their near monopolies in North Carolina towns on fine dining, tennis, and swimming.