Part i: Overview; Part ii: Cherokee origins and first European contact; Part iii: Disease, destruction, and the loss of Cherokee land; Part iv: Revolutionary War, Cherokee defeat and additional land cessions; Part v: Trail of Tears and the creation of the Eastern Band of Cherokees; Part vi: Federal recognition and the fight for Cherokee rights; Part vii: Modern-day Cherokee life and culture; Part viii: References and additional resources

See also: Rutherford's Campaign

When the Revolutionary War erupted in 1775, John Stuart, British superintendent of the South, planned to use Indian tribes in conjunction with English troops against the colonists. White encroachers at the Tennessee-North Carolina border along the Watauga, Nolichucky, and Holston Rivers, as well as a delegation of Shawnee and other northern Indians urging the Cherokee to fight against the Americans, inspired their decision to aid the British. The Upper Cherokee planned a three-pronged attack on the intruders along the North Carolina and Virginia frontiers. The Cherokee Middle Towns were to attack North Carolina, while the Lower Towns were to attack South Carolina and Georgia. The Lower and Middle settlements met with limited success. In reaction to these attacks, Gen. Charles Lee, commander of the southern Continental forces, urged a joint punitive expedition, known as the Cherokee Campaign of 1776. Under Col. Andrew Williamson, South Carolina troops moved against the Lower Towns and then traveled northwest to join the North Carolina forces under Gen. Griffith Rutherford in devastating the Middle and Valley Towns. Virginia troops under Col. William Christian crushed the Overhill Towns in present-day Tennessee. More than 50 Cherokee towns were destroyed in the summer of 1776, and the survivors were left without food or shelter.

These attacks devastated the Cherokee people, who sued for peace, giving up huge parcels of land in the process. The treaties signed after the Cherokee Campaign of 1776 marked the first forced land cessions by the Cherokee, and for the first time the land ceded was not unsettled hunting grounds but the sites of some of the tribe's oldest towns, in which the Cherokee people had lived for centuries. The Cherokee Campaign of 1776 also caused a schism between the old chiefs and young warriors. Many of the latter withdrew to Tennessee and northern Alabama, where they became known as the Chickamauga Cherokee and continued to fight white Americans until 1794.

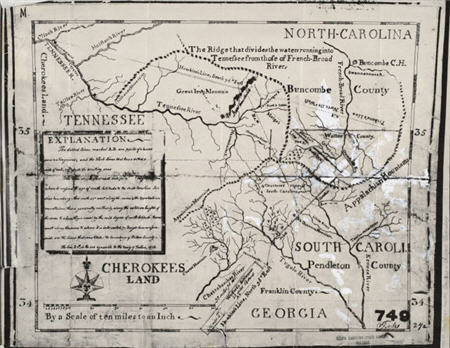

While the American Revolution brought independence to white North Carolinians, the region's Indians, including the Cherokee, were a conquered people. Nevertheless, the Cherokee managed to maintain a semblance of political independence and cultural integrity despite military defeat. With the Treaty of Holston (1791), the United States initiated a "civilization" program aimed at assimilating the Cherokee people into the mainstream of American society. To a great extent this meant the adoption of sedentary agriculture. Consequently, with Indians living by means of farming, their huge hunting grounds would no longer be needed and whites could easily acquire more Cherokee land. The Tellico Treaty was signed in 1798 as a result of the movement of settlers into Cherokee territory in western North Carolina, west of the 1791 Holston Treaty line. The Tellico Treaty specified that a line, called the Meigs-Freeman Line, was to be drawn from the "Great Iron" or "Smokey" mountain in a southeasterly direction so as to exclude settlers from Cherokee territory. War Department agent Return Jonathan Meigs supervised the running and Thomas Freeman the surveying of the line from July through October 1802. They were assisted by Cherokee leaders and settlers. The line ran from the peak of Mount Collins (located between Clingman's Dome and Newfound Gap) to a point on the North Carolina-South Carolina border near the southwestern corner of Transylvania County.

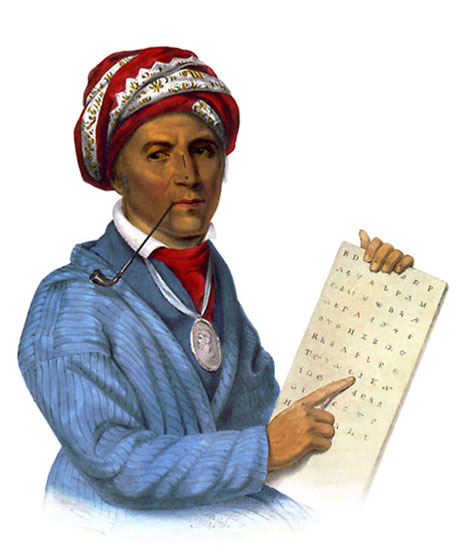

Within their newly established boundaries, the Cherokee took the lead in adopting Euro-American ways in the early nineteenth century, establishing schools and a bicameral tribal legislature. In the 1820s, the Cherokee Sequoyah invented a syllabary that enabled his people to read and write in their own language, and a bilingual newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix, soon began publication. Cherokee men and women took up farming of cotton, flax, and livestock, and engaged widely in trade with whites. Some Cherokees even built columned plantation houses and purchased enslaved people to emulate white aristocracy. Historians have referred to this period of recovery as the "Cherokee renaissance."

Despite the successes of this period, which saw the Cherokee willingly embrace white culture, seeds were also planted for a new and even greater crisis for the Cherokee people. In an attempt to save land that had been lost after the Creek War of 1813, the Cherokee signed two more treaties in 1817 and 1819. The 1817 treaty was the first Cherokee treaty that included a provision for their removal from North Carolina lands. The treaty proposed exchanging Cherokee lands in the Southeast for territory west of the Mississippi River. The government promised assistance in resettling those Cherokees who chose to remove, and approximately 1,500-2,000 did. The Treaty of 1817 also contained a proposal for an experiment in Cherokee citizenship. Cherokees who wished to remain on ceded land in the East could apply for a 640-acre reserve and legal rights as American citizens.

In 1819 the remaining Cherokees who opposed removal negotiated still another treaty. During the period from 1783 to 1819, the Cherokee people had lost an additional 69 percent of their remaining land. Although the tribe ceded almost 4 million acres by the 1819 treaty, they hoped that this additional cession would end any further removal effort. In fact, the Cherokee National Council agreed that they would not enter into any more negotiations involving the giving up of "even one foot of land." The continuing westward movement of North Carolina settlers usually brought whites into conflict with Indians, however, especially those on whose land gold was discovered in 1828. These whites were reaching into lands that treaties supposedly had guaranteed to the Cherokee. Yet instead of enforcing the treaties, the U.S. government—with President Andrew Jackson leading the way—decided to relocate the Cherokee people.