18 Jan. 1894–14 Feb. 1983

Marion Allen Wright, attorney, citizen of the two Carolinas, and firm supporter of civil rights, was born in Johnston, Edgefield County, S.C., the youngest of ten children of Confederate veteran Preston and Octavia Watson Wright. Both parents died before his sixth birthday, and he was reared by an older sister, Mabel, and her husband, William D. Holland, who lived in nearby Trenton. U.S. Senator Benjamin Ryan Tillman was a neighbor of the Hollands, and as a teenager Wright stayed in the Tillman home as protector for Mrs. Tillman and the daughters during the senator's frequent trips from home. The Tillman library was well stocked with the classics, and young Marion was encouraged to make use of its holdings. The Hollands were unenthusiastic about their ward's association with Senator Tillman because of his use of profanity and the fact that while governor he had instituted the dispensary system for state control of liquor sales; his racial views disturbed them not at all.

At sixteen Wright enrolled in the University of South Carolina, and at that tender age there was little to indicate that his future would be so dedicated to justice, tolerance, and the protection of human rights. True, as a boy he had witnessed racial incidents that had left an impression, but it was at the university and in the city of Columbia that his social conscience was fully awakened. By his own admission Wright was an indifferent student, but classes with President Samuel Chiles Mitchell and Professor Josiah Morse exerted a tremendous influence in shaping his outlook on society. President Mitchell in his political science class focused the attention of his students on the need for better public schools, the establishment of public library facilities, and the provision for public health agencies. Morse, a Jew who taught one of the first courses offered in the South dealing with race relations, openly criticized discrimination and prejudice of any kind. Wright became a friend and admirer of both men.

Also important was Wright's experience while working as a part-time reporter for the Columbia Record at a time when the Ku Klux Klan was particularly active in espousing anti-Jewish and anti-Catholic sentiments. Through friendship with his supervisor at the Record, William Carmack, a Catholic, Wright came to realize the prejudice faced by members of that religious body. But of more significance in the development of his social conscience were assignments by the Record to witness and report on the first sixteen electrocutions at the state penitentiary, a practice begun in 1912; thirteen Black and three white inmates were the victims. The experience was revolting and explains why in later years Wright spent untold hours supporting efforts to abolish capital punishment.

Wright left the university in 1914 without receiving a degree. Moving to Winston-Salem, he worked with his brother in the real estate and insurance business, according to a statement he made in a 1978 interview. Arnold Shankman reported that the time was spent teaching school. The answer probably is that Wright did both. While living in Winston-Salem he married Lelia Hauser, and in 1916 the couple moved to Columbia, S.C.; Wright entered the university's law school, and his wife was employed by August Kohn, a prominent Jewish resident for whom both developed affection and respect.

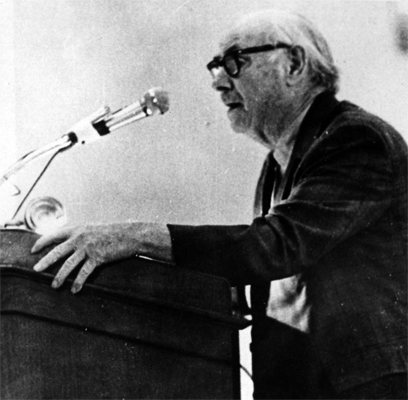

After obtaining a law degree in 1919, Wright moved to Conway, S.C. There, and later in nearby Myrtle Beach, he established offices for what developed into a highly successful practice of corporate and business law. Conway's Black population was small, but Wright soon took note of the unpaved streets in the Black section of town, the lack of sanitary facilities available to African Americans, and the limits placed on their use of the Conway hospital. These facts moved him steadily forward in his commitment to equal treatment for all citizens. Wright was a gifted speaker, and as opportunities arose he began to call for justice to African Americans and the establishment of public libraries, and to express disapproval of the death penalty.

In 1919, shortly before or after settling in Conway, he was invited to deliver the commencement address to the high school seniors. Speaking on civil rights, he stated that Black Americans should be allowed to vote in the Democratic primary and to serve on juries. These remarks received a cool reception, and following the exercises the chairman of the school board challenged Wright's views. To the credit of both, the gentleman later became a friend and valued client of Wright. In 1927 Wright accepted the invitation extended by citizens of Marion to be the speaker for the Memorial Day observance on 10 May. After paying due tribute to the Confederate dead, he declared that the time had come "when the political rights of the Negro must have ample protection"; no people could reach their full potential when deprived of political rights, he observed.

Neither these addresses nor other forthright expressions of his views appear to have affected Wright's popularity or to have diminished the esteem with which he was held. He was elected president of the University of South Carolina Alumni Association (1935–37) and served a term as president of the university's Law School Alumni Association. Such evidences of confidence and tolerance can best be explained by Wright's obvious ability, the wit and charm that characterized his handling of controversial issues, and his magnificent power of personal persuasion.

His championship of equal rights for all citizens, justice that is color blind, and abolition of the death penalty are common knowledge, but less known is the support he gave to public libraries. To him librarians were an indispensable agency in the education of the citizenry, and in the 1930s he joined wholeheartedly with a loosely organized group of South Carolinians known as the Citizens Library Association to promote library service. He was elected president of that organization and later became chairman of the South Carolina Library Board. South Carolinians are indebted to Marion Wright, as much as to any other person, for the evolution of small, locally operated, inadequate libraries into an effective statewide system. His interest in libraries and his belief in the importance of education led him to serve for a term as chairman of the South Carolina Commission on Adult Education. Furthermore, such interest did not end with retirement; after moving to North Carolina Wright opened his personal library, with its books and wide list of newspaper and magazine subscriptions, to the school children of Linville Falls.

In 1919, during the dark days of racial conflict and Ku Kluxism that followed World War I, the Commission on Interracial Cooperation was born. A number of southern liberals gave it their support, and in 1944 members from this group organized the Southern Regional Council with the primary objective of promoting racial justice. Many of these men and women believed in all honesty that the racial tensions could be solved through separate but truly equal facilities for schools, hospitals, rest rooms, and parks. Wright disagreed. He regarded it a waste of time and talent to teach the ABCs and multiplication tables separately to white and Black children. To his well-meaning friends he posed the question of morality in expecting some citizens to await future delivery of their natural rights. In November 1945 Wright became a member of the board of the Southern Regional Council and was reelected continuously for some thirty years; from 1952 until late 1958 he was president of the council. After serving on the council's board and executive committee, he was honored with the title Life Fellow.

Wright's concern for educational opportunities for African Americans undoubtedly prompted his interest in Penn School, located on St. Helena Island off the South Carolina coast. He was a member of its board of trustees in 1947 and 1948 and chairman of the board from 1965 to 1971. For over three-quarters of a century Penn Normal, Industrial, and Agricultural School had operated as the educational agency for Black people living on the island, but in May 1948, following a study and recommendations by Dr. Ira DeA. Reid, the trustees decided to relinquish responsibility for the academic program to the state and to abandon the farm program. At the same time the name was changed to Penn Community Services, and future emphasis was to be on support of the island's economic development, with continued assistance for the improvement of public health facilities.

In 1948, Marion Wright moved to Linville Falls, N.C. He became instrumental in the establishment of the Linville Gorge Wilderness and its inclusion in the National Parks system in 1964 after petitioning the National Park Service and John D. Rockefeller, Jr. , then owner of the land. Wright and Sam Weems, superintendent of the Blue Ridge Parkway, took Rockefeller and his son to an outing at the falls. Rockefeller, then committed to preservation of the area, donated the land to the state. The state subsequently transferred the land to the federal government. A plaque honoring Wright, Weems, and Rockefeller sits in the visitors center at Linville Falls. By this move North Carolina gained a citizen who for the next three decades would be active in behalf of civil rights, efforts to abolish the death penalty, the support of public libraries, and the cause of equal educational opportunities for all. He became a member of the national board of the American Civil Liberties Union and of North Carolina's first State Advisory Committee to the U.S. Civil Rights Commission, and he continued his membership in the NAACP. In 1969 the North Carolina Civil Liberties Union presented him with the Frank Porter Graham Award. Yet no cause was closer to Wright's heart than abolition of the death penalty; becoming founder and first president of North Carolinians against the Death Penalty, he worked diligently for the remainder of his life to secure passage of the necessary legislation.

Lelia Wright died in October 1956, and Marion Wright remained a widower until 1970, when he married Alice Norwood Spearman, a widow with whom he had been associated as a fellow member of the South Carolina Advisory Committee for the Civil Rights Commission. Alice Wright shared her husband's devotion to civil rights and in 1973 was herself the recipient of the Frank Porter Graham Award. Wright died a few weeks after his eighty-ninth birthday, and his body was willed to the Duke University Medical School.

Though a man of deep religious feelings, Wright was not a member of any church. Detailed information about his private life, as well as the dates related to his public career, are in many instances difficult to establish. Information such as an entry in Who's Who in America would have contained must have seemed unimportant to him; until the end his chief concern was the establishment of fair treatment under law for all mankind and the removal of any statute that denied basic civil rights to any citizen.

Wright gave the bulk of his papers to the Southern Historical Collection of The University of North Carolina library; they consist largely of correspondence with the various agencies with which he was associated either by interest or membership, plus copies of his numerous speeches. Additional folders contain correspondence with his brother, Preston, his sisters, Helen and Kathleen, and his nephews. The Dacus Library of Winthrop College and the South Caroliniana Library of the University of South Carolina each hold smaller groups of Marion A. Wright Papers. Within the three collections there is some duplication.