22 Apr. 1792–11 Mar. 1867

James Phillips, educator and clergyman, was born at Nevenden, Essex, England, a small village about twenty miles northeast of London. He was the second of the three sons of the Reverend Richard Phillips, rector of the parish, and Susan Meade Phillips. James's mother died when he was about seven, and in 1800 his father moved to Roche, Cornwall, where he married again and James's older brother, John, died. There were children by Richard Phillips's second marriage, and conflict with their stepmother drove James and his remaining brother, Samuel, from the home. The break was so complete that neither James nor Samuel ever saw their father again. Samuel entered the British navy, and James worked as a bookkeeper in Plymouth, an important seaport during the war with Napoleon then in progress. James soon taught Latin in a boys' school, meanwhile studying higher mathematics on his own. While living in Plymouth, he once saw Napoleon pacing the deck of the Bellerphon just before he was carried into exile on St. Helena.

Following Samuel's discharge from the navy at the end of the war in 1815, the two Phillips brothers emigrated to the United States. Arriving in New York, they soon found employment as teachers in a boys' school and within a few months established their own private academy for boys in Harlem, then a separate town from New York City. In 1821 James Phillips married Judith Vermeule of Plainfield, N.J. A well-educated young woman, who had been taught Latin, Greek, and French, she was a descendant on both sides of old, prominent Dutch families of New York and New Jersey.

In 1826 Phillips became professor of mathematics and natural philosophy at The University of North Carolina. After about 1835 most of his teaching was in mathematics. An industrious scholar and an exacting teacher, he wrote out in full many of the lectures he gave his advanced classes, reporting in clear, elegant prose the results of the latest research. He was the author of a textbook, Elements of the Conic Section (1828). A sturdy, heavy-built man with an iron constitution, he was feared by students because of his burly appearance and brusque speech as well as his reputation—deserved or not—for skill in fencing and the use of the single stick. The knotted walking stick he habitually carried was a thing of awe.

In 1832 Phillips joined the Presbyterian church and soon became active as a lay preacher. In 1833 he was licensed to preach by Orange Presbytery and in due time was ordained and installed as minister of the New Hope Presbyterian Church, located about seven miles outside of Chapel Hill. He shared the work of the university chapel with Professor Elisha Mitchell and spent much of his summer vacations making evangelizing tours across the state. He studied theology, as he had mathematics, on his own, reading the standard works in the field, and became a recognized scholar in divinity. In 1851 The University of North Carolina honored him with the D.D. degree. Apparently Phillips was not a political activist, but his sympathies seemingly lay with the Whigs.

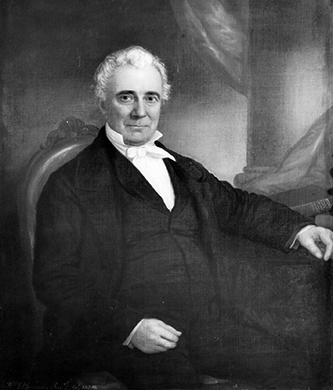

At about 9 o'clock one morning, as he was waiting to begin a class in geometry, Phillips fell dead in his classroom. He was buried in the Chapel Hill Cemetery. His carefully chosen library, mostly theological, was later donated to the university by his daughter. An oil portrait of Phillips by William Garl Brown, signed and dated 1859, is owned by the Dialectic Society of The University of North Carolina.

Each of the three Phillips children played a significant role in the history of the state. The oldest, Mrs. Cornelia Phillips Spencer (1825–1908), was a writer of note and has been given much credit for the reopening of The University of North Carolina (1875) after Reconstruction. The second, Charles Phillips (d. 1889), was a Presbyterian minister and taught mathematics at both The University of North Carolina and Davidson College and engineering at The University of North Carolina. The youngest, Samuel Field Phillips (d. 1903), was an attorney and legal educator. He served as state auditor during the first term (1862–65) of Governor Zebulon B. Vance and as U.S. solicitor general under President Ulysses S. Grant.