pre-1741–16 Oct. 1826

See also: United Methodist Church

James O'Kelly, clergyman, was an early Methodist itinerant who seceded from the Methodist church and headed a movement that became the southern Christian church. In 1931 this denomination and the Congregationalists formed the Congregational Christian church. A merger between the latter denomination and the Evangelical and Reformed church in 1957 resulted in the formation of the United Church of Christ.

Of Irish ancestry, O'Kelly was born either in Ireland or in the colony of Virginia. Nothing is known of his early life except that, according to his statement, he was born of poor parentage. He married Elizabeth Meeks, reportedly on 25 June 1759, and in 1787 they were listed among the homeowners of Mecklenburg County, Va. About 1797 the O'Kellys moved to Chatham County, N.C., and were living there when the minister died. They had two sons, John and William. John was apparently a farmer. William represented Chatham County in the North Carolina legislature in 1805 and in four later sessions. He was elected to the state senate in 1818 and died the following year while still in office. He left many known descendants.

In 1775 James O'Kelly joined the Methodist Society in Virginia, and three years later his name first appeared in the records of the Virginia Methodist Conference as a minister on trial. At the same meeting, he was assigned to assist Beverly Allen in the New Hope Circuit in North Carolina. His popularity and influence as a preacher grew rapidly in the area that he traveled.

When the American Revolution began, O'Kelly attempted to obey the instructions of John Wesley and remain neutral. However, after he had been robbed, falsely accused, half starved, twice captured, and generally mistreated by the British forces, he became an outright Patriot. He related that he stood his draft, engaged in exhausting military marches, and served in the army during the hostilities.

The Methodist itinerants were not ordained clergymen but evangelists within the Church of England. Consequently, the sacraments of the church could be administered to the members of the society only by official Anglican priests. Because of the Revolution, there were few such ministers to serve the needs of the increasing number of Methodists. As a result, when the Virginia Methodist Conference met in 1779, O'Kelly joined with eighteen of his fellow circuit riders in approving a decision to appoint a committee from among their number to administer the sacraments and to ordain ministers. This action was condemned as illegal by Francis Asbury, who had assumed leadership of the Methodists during the war. As a result of his decision, the Methodist Episcopal church was organized at the celebrated 1784 Christmas conference in Baltimore, with Thomas Coke and Francis Asbury ordained as bishops and James O'Kelly and his fellow evangelists ordained as ministers.

A period of intense activity followed during which Asbury appointed O'Kelly district superintendent in a Virginia area, where the minister soon became one of the most efficient cohorts of the bishop. Tributes to his rise in stature as a preacher were paid by his colleagues, including Freeborn Garrettson, John Kobler, James Meacham, Richard N. Venable, Philip Gatch, and William McKendree. Among his actions was a fearless denunciation of slavery; as a testimony to his conviction, on 5 Mar. 1785 he manumitted the only slave he ever owned. Four years later, he wrote and published a condemnation of the institution entitled Essay on Negro-Slavery.

Despite his ministerial success and his close association with Asbury, O'Kelly began to have misgivings about the increasing autocracy of the bishop. While the southern clergyman had acquiesced in the elevation of Asbury to the bishopric, he did not wish to see the rise of an infallible hierarchy and he feared that individual ministers were in danger of losing the right to express a voice in their affairs. He was offended when the venerable Wesley's name was dropped from the American General Methodist Conference rolls, and he opposed the formation of a Bishop's Council in 1789, although he was made a member of that body.

Rising dissension came to a head at the General Conference held in Baltimore in 1792. O'Kelly proposed that legislation be passed giving each clergyman the right to accept or protest his appointment to territory by the bishop. After lengthy and acrimonious debate of the issue, the Conference defeated O'Kelly's proposal by a majority vote. Feeling that he could not accept this ruling and its implications, O'Kelly, together with several ministers of similar convictions, left the Conference and returned to Virginia. As efforts were continued to reach a compromise, the Virginia ministers petitioned Asbury to meet with them to discuss the government of the church. The bishop's refusal was delivered to the Methodists when they met for their conference at Mannakin-town in 1793. Despairing of any remedy for what he considered to be an impossible situation, James O'Kelly then seceded from the Methodist Episcopal church, accompanied by a number of his ministerial colleagues and their parishioners.

On 4 Aug. 1794 the secessionists met in Surry County, Va., to organize their own church. The name "Republican Methodists," denoting opposition to an episcopal form of government, had been used for two years previously. Because of its similarity to Thomas Jefferson's growing political party, this appellation was abandoned, although a small group continued to use it for a number of years. The decision was made that "Christian" was an appropriate name for the church. Furthermore, the organizers declared that the Bible was a sufficient creed, and they recognized the right of individual interpretation of the Scriptures. Government was to be by majority vote in the local congregations as well as in the annual conferences. The Surry meeting was the beginning of the southern Christian church, which was never connected with the Christian church headed by Barton W. Stone. (In 1922 it united with the New England Christians, who were followers of Abner Jones and Elias Smith.)

The formation of the new church group, often referred to as "O'Kellyites," touched off the publication of a veritable shower of pamphlets—by both the Methodists and the Christians—containing charges and countercharges of heresy, personal ambition, illegal actions, and the flagrant use of falsehoods. O'Kelly added fuel to the fire in 1798, when he published The Author's Apology for Protesting against the Methodist Episcopal Government. The next year he wrote a pamphlet, entitled An Address to the Christian Church under the Similitude of an Elect Lady and Her Children, urging all Christian denominations to consider a general ecumenical plan. This idea, which was far ahead of its time, was generally either ignored or ridiculed. After its author published A Vindication of the Author's Apology, with Reflections on the Reply in 1801, the battle subsided. The following year, a reconciliatory meeting took place between O'Kelly and Asbury.

The founder of the new church devoted his remaining years to the task of building a denomination. This did not prove to be easy, as many disagreed with his views. He firmly believed that the Holy Trinity was composed of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit as three distinct persons and not one tripartite God. While he respected freedom of choice in the mode of baptism, he strongly preferred sprinkling to immersion, and he would agree to no written man-made creed for the church. In addition, O'Kelly vigorously opposed the increasingly popular institution of slavery as unchristian. In support of his efforts, he published Hymns and Spiritual Songs Designed for the Use of Christians (1816), The Divine Oracles Consulted; or, An Appeal to the Law and Testimony (1820), Letters From Heaven Consulted (1822), and The Prospect Before Us, By Way of an Address to the Christian Church (1824).

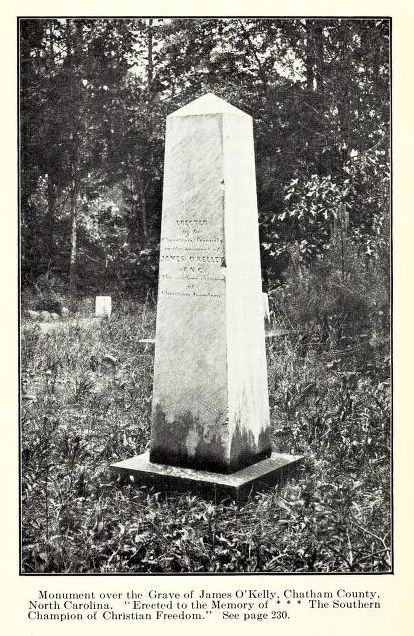

No portrait or accurate physical description of O'Kelly has been found. The Ordination of Francis Asbury, which hangs in Lovely Lane Museum, Baltimore, includes every person known to have been present on the occasion. The artist, Thomas Coke Ruckle, who had no description of O'Kelly, solved his problem by positioning the figure in front of him so as to obscure almost all of O'Kelly's face and figure. Nevertheless, there is abundant testimony to the magnetic personality and influence of the minister. His friends and admirers donated land and built a church for him near his Chatham County home and named it O'Kelly Chapel. The clergyman preached in this church as long as he was physically able and was buried in its adjacent cemetery when he died. The Christian church erected a fitting marker over his grave; another impressive memorial stands in the center of the campus at Elon College. However, the greatest memorial to James O'Kelly is the church that he founded, which survived and grew slowly but steadily into a denomination.