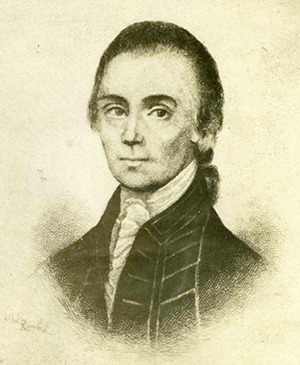

ca. 1740–2 Dec. 1786

See also: Abner Nash, Research Branch, NC Office of Archives and History

Abner Nash, Patriot and second governor of the state of North Carolina, was born at Templeton Manor, his family's plantation near Farmville in Prince Edward County, Va. His father, John Nash, the son of Abner Nash of Tenby, County Pembroke, Wales, had immigrated to Virginia about 1730. His mother, Ann Owen Nash, was the daughter of Sir Hugh Owen, second baronet of Orielton. Where young Nash received his education is unknown, but his later ability as writer and orator testifies to a superior classical training. He was qualified to practice law before the Prince Edward County bar in 1757, and in 1761 and 1762 he represented that county in the Virginia House of Burgesses.

In 1762 or early 1763 Nash moved to Hillsborough (then Childsburgh), N.C., with his younger brother Francis. An older brother, Thomas, had settled in Edenton four years earlier. Abner remained in Hillsborough long enough to acquire some town lots, dam the Eno River, and build the town's first mill. By 1764 he had moved to Halifax to practice law. Here he resided for about twelve years, representing the town in the House of Commons in 1764 and 1765. From 1770 to 1771 he was Halifax County's representative in the house. During the session of 1770, a bill was introduced to establish a seminary of learning at Charlotte. Nash was appointed one of the first trustees of Queen's Museum (later Queen's College).

While in Halifax, he married Justina Davis Dobbs, the widow of Governor Arthur Dobbs. When Dobbs's executors—his two sons by a former marriage—failed to pay their father's bequest to the youthful widow, Nash brought suit. An attachment was issued. The defendants obtained an injunction, which the provincial chancery court made perpetual. In response to an appeal by Nash, the Privy Council in London reversed the decision. This suit, known as the "Martin court quarrel," caused a bitter controversy between Governor Josiah Martin and the Assembly, with the result that all courts of law, except those held by single justices of the peace, were closed for a time in the province. This event gave much impetus to the Revolutionary movement in North Carolina.

Justina Nash died in 1771, leaving three small children. Within a year, Nash moved to New Bern and married Mary Whiting Jones, of Chowan County, the daughter of Harding and Mary Whiting Jones. The Nash plantation, Pembroke, located on the Trent River above New Bern, became their home. Here the family lived until the American Revolution, when they were forced to flee before the British advance under Major James H. Craig in August 1781. The house was burned and with it all the family's possessions, records, and papers.

An ardent Whig, Nash had been an early leader in the opposition to Governor Martin, who spoke of him as "an eminent lawyer, but an unprincipled character" and recommended him, among others, for proscription. After Martin fled the colony in 1775, Nash took an active part in the interim government, serving on the Committee of Safety, as a member of the Provincial Council (1775), and as a delegate to all four Provincial Congresses. During the session of 1776, he prepared the resolution that announced North Carolina's stand for freedom and independence. He became the first speaker of the House of Commons of the new state.

In March 1777 Nash was again elected to the House of Commons from New Bern and became speaker. In 1778, while representing Craven County, he was elected to the Continental Congress but declined to serve. In 1779 he represented Jones County in the North Carolina Senate, succeeding Allen Jones as speaker. In 1780 he was elected second governor of the new state.

His term of office as governor, extended by act of the legislature until 25 June 1781, was an unhappy one from the start. The fall of Charles Town, the disastrous defeat at Camden, and the depleted resources of the state all gave heart to the Loyalist faction, estimated to have been half of the state's population. Governor Nash, finding the General Assembly and his own Council too dispersed and unwieldy to be of much help in guiding a state at war, requested a Board of War of three members. He soon bitterly regretted this request. Early on the members proved inadequate for their task and later actively opposed the governor, intercepting his correspondence with the generals in the field and flouting his authority as commander in chief.

The mounting problems of providing and equipping an army, the tensions between governor and Board of War, and the loss of his home and possessions all took their toll of Nash's never-robust health. He declined nomination for a second term in 1781 and became a member of the Continental Congress in 1782, serving as regularly as his health would allow until his death.

His children by his first marriage were Abner, Jr., who died young; Margaret, who married Thomas Haslin; and Justina, who never married. By his second marriage, he was the father of Ann, who never married; Eliza, who married Robert Ogden IV; Maria, who married George W. B. Burgwin; Frederick, who married Mary Goddard Kollock; and Francis, who died young. His widow later married David Witherspoon of Craven County.

Nash was also an enslaver. In his November 1786 will, he bequeathed ownership of several enslaved people between his children, in-laws, and his second wife. Many of the people enslaved by Nash are named explicitly. To his daughter, Maragaret, and her husband, Thomas Haslin, Nash left "17 or 18" enslaved people. To his son, Abner, Jr., Nash named the specific enslaved people he wished willed; Blue, Jack, Lizza, Johnny, Tommy Mark, Tenah, Jammy, Phebe, Newton, Congo Will, Lylla Judah, and Tom are all named explicitly. To his daughter, Justina, Nash willed "two of the youngest sons" of an enslaved person named Diana and an endowment to purchase four enslaved boys "between the age of 8 and 12 years." Lastly, to his "present wife" (Mary Whiting Jones), he left all enslaved people that he "attained by marriage with her and their increase."

Nash died "of consumption" in New York City while attending the Congress in 1786. He was initially buried in St. Paul's churchyard there, but later his remains were reinterred in the family vault at the Pembroke Plantation in North Carolina.