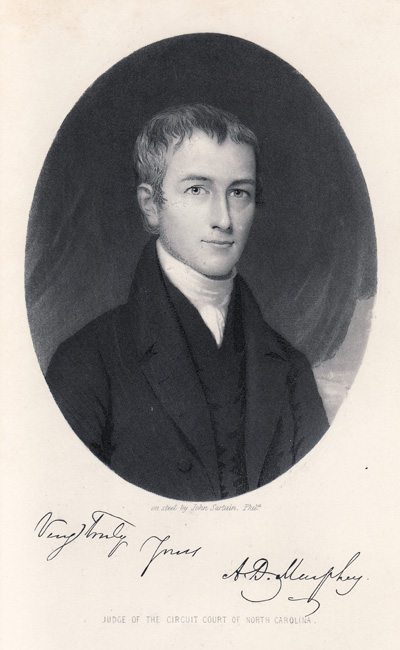

ca. 1777–1 Feb. 1832

Archibald DeBow Murphey, attorney, legislator, jurist, and manuscript collector, was born near Red House Presbyterian Church in Caswell (then Orange) County, one of seven children of Archibald and Jane DeBow Murphey. His father, a native of Pennsylvania, moved to the Red House community in 1769 and purchased about five hundred acres on Hyco Creek; there he constructed a frame house consisting of two rooms with an attic and a cellar. This simple structure was a curiosity in a community of predominantly log residences and was generally referred to as Murphey's Castle. In the community the elder Murphey met and married Jane DeBow, a native of New Jersey, whose parents had preceded him to North Carolina; he farmed, served with American forces in the Revolutionary War, and was clerk of court in Caswell County from 1780 to 1816. He was a man of some learning; his surviving books carry a plain printed bookplate reading: "A. Murphey, Caswell, N.C."

Archibald D. Murphey did not discuss his childhood in his rather voluminous extant writings, but it is known that he attended David Caldwell's "college" at Greensboro before entering The University of North Carolina in 1796. At Chapel Hill he excelled in his studies, won the confidence of his teachers, and was graduated with honors in 1799. Murphey was immediately hired as tutor in the preparatory department, and the following year he was appointed professor of languages, one of only three members of the entire faculty. He also served as librarian and clerk to the faculty. In 1801 he resigned and moved to Hillsborough to live with and study law under William Duffy. In the same year he married Jane Armistead Scott, the daughter of John Scott of present-day Alamance County.

Licensed to practice law, Murphey purchased his father-in-law's home, the Hermitage, near the Hawfields community, and over the next decade built up an estate of about two thousand acres, including a gristmill and a sawmill near the present town of Swepsonville and an eighty-gallon distillery nearby. He also enslaved a large number of people. Soon he enlarged his home and built in the yard a law office, which served as a convenient place to keep his farm and legal accounts as well as a meeting place for his clients. His wagons frequently made trips to Petersburg, carrying flour, whiskey, and other produce. During this period Murphey invested heavily in other properties, including Lenox Castle at Rockingham Springs. These properties, acquired with borrowed money, taxed his resources and, coupled with his wife's continued illness, impaired his career.

Much of Murphey's legal work centered around the county seat at Hillsborough, where he built a solid reputation as a lawyer. Turning to public service, he was a member of the state senate from 1812 to 1818, and while in that office he made his greatest contributions to the state. Recognizing North Carolina's backwardness, he proposed bold programs for progress, especially in regard to education and internal improvements. In 1817 he submitted his celebrated report advocating a publicly financed system of education. Noting that "one of the strongest reasons which we can have for establishing a general plan of public instruction, is the condition of the poor children of our country," Murphey argued that the state could not expect to progress dramatically until it elevated the educational status of its population. His plan encompassed primary schools, academies, and the university; when he had finished it on 29 Nov. 1817, he wrote his friend Thomas Ruffin: "I bequeath this Report to the State as the Richest Legacy that I shall ever be able to give it."

Two years later Murphey submitted his "Memoir" on internal improvements, in which he recommended a vigorous program to open rivers and canals and construct roads. He wrote: "If North Carolina had her commerce concentrated at one or two points, one or more large commercial cities would grow up; markets would be found at home for the productions of the State; foreign merchandize would be imported into the State for the demands of the market; our debts would be contracted at home; and our Banks would be enabled to change their course of business."

Murphey's proposals for public expenditures for education and for a bold system of land and water transportation were largely ignored by his fellow legislators. North Carolina, soon to be characterized as the "Rip Van Winkle State," was not yet ready for such advanced ideas.

In 1818 the General Assembly elected Murphey to a judgeship in the superior court. The extensive travel involved in the position and Murphey's need to give more attention to his business affairs, however, led to his resignation after only two years on the bench. He resumed his law practice but became increasingly interested in compiling a history of the state. This undertaking was plagued by the deterioration of his physical and financial condition. A lottery was authorized by the General Assembly for the support of Murphey's history, but the proceeds were insufficient to be of substantial help and the history was never written. Murphey was, however, the state's first major collector of manuscripts, and his papers, even though scattered after his death, were of great value to later historians.

Throughout his life Murphey overextended himself financially. Although he apparently was in an enviable monetary position by 1812, within eight years his property was heavily mortgaged and he was unable to pay his debts. One crisis after another occurred as rheumatism wracked his body and as his investments—some in the internal improvements schemes that he championed—proved unsound. The ultimate indignity came in 1829, when, despite the fact that as a legislator he had sought to abolish imprisonment for debt, he himself was incarcerated in Greensboro for twenty days because he could not pay off a note.

Archibald D. Murphey's vision of the future surpassed that of his generation. Measured only against his contemporaries, he was an apparent failure, for few of his proposals were immediately carried out. However, his agitation for public education helped bring about the establishment of the State Literary Fund in 1825 and the first public school act seven years after his death. His zeal for the preservation of the history of the state infected others such as David L. Swain and John H. Wheeler, and the materials that he had collected are still used a century and a half later. And his proposals for overland and water transportation, though somewhat outdated with the coming of railroads, continued to emphasize the need for North Carolina to cast off its dependence on Virginia and South Carolina for markets. Thus Murphey was far more than a dreamer. He was, indeed, a prophet of an awakened state.

Murphey died at age fifty-five, leaving five children who reached adulthood: William Duffy, Victor Moreau, Cornelia Anne, Peter Umstead, and Alexander Hamilton. He was buried in the cemetery at the Presbyterian Church in Hillsborough.