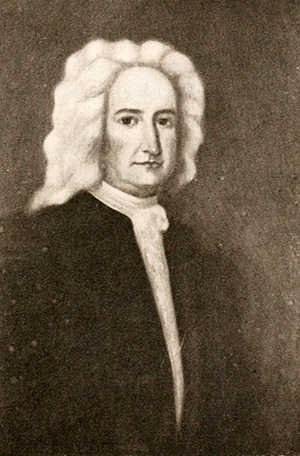

ca. 1638–ca. 1723

See also: Philip Ludwell, Research Branch, NC Office of Archives and History

Philip Ludwell, governor of North Carolina, governor of South Carolina, and Council member, secretary of state, and speaker of the House of Burgesses in Virginia, was the son of Thomas and Jane Cottington Ludwell of Bruton Parish, Somersetshire, England. About 1660 he emigrated to Virginia, where his older brother, Thomas, was a member of the Council and another native of Bruton, Sir William Berkeley, was governor. The Ludwell brothers, who are believed to have been cousins of Berkeley, were members of the governor's small circle of close friends and were among his leading political supporters.

In the spring of 1675 Philip Ludwell was appointed to the Council and became deputy secretary of state under his brother, who held the office of secretary but was leaving for England on official business. Philip was deputy secretary until the summer of 1677. He later served briefly as secretary in his own right.

Philip was one of Berkeley's chief aides during Bacon's Rebellion, which occurred while Thomas was in England. As a colonel in the militia he commanded troops that captured prominent leaders in the uprising, and as a Council member he participated in most of the trials of the rebels. He ardently defended the governor's handling of the rebellion, even after Berkeley's recall to England and his death there in 1677.

Ludwell quarreled with Berkeley's successor, Herbert Jeffreys, who removed him from the Council because of his bitter language. In 1681 Ludwell was reappointed by Lord Thomas Culpeper, who was then serving as governor, but he was removed again in 1687 because of his opposition to the current governor, Francis Howard, Lord Effingham. Ludwell had aroused Effingham's anger by opposing the governor's efforts to increase his own power at the expense of the Assembly.

Ludwell's opposition to Effingham won him popularity with the colonists, and in 1688 he was elected to the House of Burgesses. He was not allowed to take his seat, however, because of his status as a suspended Council member. The following year he went to London as agent for the House of Burgesses in presenting charges that the Burgesses brought against Effingham. He obtained decisions favorable to the colonists.

While Ludwell was in England, the Lords Proprietors of Carolina appointed him governor of their northern colony, issuing their commission on 5 Dec. 1689. The Proprietors had been associated with Ludwell previously, for Ludwell's wife, who was the widow of Sir William Berkeley, had inherited Berkeley's proprietorship in Carolina. By 1689, however, Ludwell had sold his wife's interest to some of the other Proprietors. His arrival in London coincided with a crisis in North Carolina, where the colonists had revolted against Governor Seth Sothel and banished him. In appointing him governor, the Proprietors gave Ludwell the task of bringing order out of the confusion resulting from several years of misrule by Sothel.

Ludwell organized his government in North Carolina in the spring of 1690. His right to office was challenged immediately by one John Gibbs, a Virginian who had gone to North Carolina, acquired land, and proclaimed himself governor about the time of Sothel's expulsion. Gibbs claimed that Ludwell's appointment was invalid, apparently basing his claim on the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina, which restricted the governorship of the Carolina colonies to resident Proprietors, heirs apparent of Proprietors, and members of the Carolina nobility (in which the ranks were landgrave and cacique). Gibbs, a relative of one of the Proprietors, had been made a cacique of Carolina in 1682, but he had settled in Virginia instead of Carolina. On the departure of Sothel, a Proprietor, there was no one in North Carolina qualified for the governorship under the Fundamental Constitutions, which no doubt prompted Gibbs's move to that colony. As Ludwell had sold his wife's proprietorship, he had no claim to the governorship other than his commission from the Proprietors, who either did not know of Gibbs's action or chose to ignore it.

In the fall of 1690, after several months of agitation and at least one episode of violence, both Gibbs and Ludwell went to London and laid the controversy before the Proprietors. Gibbs's claim was disallowed, and he returned to Virginia. The following year the Proprietors suspended the Fundamental Constitutions, directed significant changes in the government of their colonies, and appointed Ludwell governor of the entire province of Carolina. Under his new commission and instructions, issued in November 1691, Ludwell was to make his headquarters at Charles Town and appoint a deputy governor for North Carolina.

Suspension of the Fundamental Constitutions not only removed the legal basis for Gibbs's claim but also provided a solution to a problem in South Carolina, where Seth Sothel had assumed the governorship after his expulsion from North Carolina. Sothel, like Gibbs, had based his action on the Fundamental Constitutions. Thus Ludwell, as governor of the entire province under a new governmental system, had the assignment of ousting Sothel from office in South Carolina, cleaning up after him in both colonies, and reorganizing the government in both.

Ludwell arrived in Charles Town in April 1692 and published his commission and other papers from the Proprietors. Sothel challenged the validity of Ludwell's appointment, but he soon left the colony after his supporters, who had become disillusioned, withdrew their support. Despite Sothel's departure, Ludwell faced an impossible task. South Carolina had long been plagued by serious problems and bitter factional rivalries. Conditions had worsened under Sothel, who had aggravated the problems and exacerbated the animosities. Moreover, the Proprietors took adamant positions on troublesome issues, which made it extremely difficult for Ludwell to work out compromises between the local parties. Instead of bringing harmony, he found himself in the middle of a three-sided battle on practically all issues. Although he made progress in some areas, particularly in relations with the Indians, he failed to solve other problems, such as the illicit trade with pirates and the colonists' refusal to pay rent because of their dissatisfaction with land policies.

About the middle of May 1693, Ludwell left Charles Town, having informed the Council a few days earlier that he intended to go to Virginia and North Carolina to attend to governmental matters in the latter colony. He left the South Carolina government in the hands of an early settler, Thomas Smith. Although he expressed his intention to return in four months, he did not return. In November 1693 the Proprietors issued a commission appointing Smith governor of Carolina, thus formally terminating Ludwell's tenure.

Differing explanations have been offered for the sudden ending of Ludwell's administration in Charles Town. Some writers indicate that he quit in disgust; others say that the Proprietors dismissed him. The available records do not show clearly what occurred. It is noteworthy, however, that they indicate that Ludwell questioned the validity of his appointment, apparently doubting the legality of the Proprietors' suspension of the Fundamental Constitutions. The records also reveal serious differences between Ludwell and the Proprietors respecting policies appropriate for the colony and Ludwell's powers as governor. Whoever initiated the action, ending his administration probably was agreeable to both Ludwell and the Proprietors.

That the Proprietors were not entirely dissatisfied with Ludwell is evidenced by his continuing as chief executive of North Carolina for two years after he left Charles Town. Apparently the deputy governor of North Carolina, Thomas Jarvis, had become too ill to officiate, or perhaps had died, before Ludwell left South Carolina. In fact, the vacancy probably prompted, or at least precipitated, Ludwell's departure from the southern colony. By fall Ludwell had taken charge of the North Carolina government, which he presided over until the summer of 1695. As in his earlier period of governing the colony, Ludwell resided in Virginia, presiding intermittently over the North Carolina government in person and governing through a deputy in the intervals between visits.

Ludwell solved a serious problem in North Carolina, namely, discontent with land policies and refusal to pay rents. The colonists were resentful because the Proprietors had rescinded concessions they had made in 1668 and had promulgated more stringent policies than those to which they had agreed. The colonists maintained that the 1668 concessions were irrevocable and the later policies invalid. Ludwell agreed with the colonists, and on 28 Nov. 1693 he announced that he would grant land under the terms specified in 1668, which he did. Although the Proprietors appear not to have been consulted on the matter, some years later, on the recommendation of Governor John Archdale, they accepted Ludwell's view.

Ludwell also supervised the reorganizing of the government to conform to the instructions the Proprietors had issued in 1691. By the summer of 1695, when his role in North Carolina ended, the colony had a stable government as well as acceptable land policies. For the first time in its history, North Carolina was experiencing a period of relative calm and prosperity.

By 1695 Ludwell's public career was nearing its close. That year he was speaker of the Virginia House of Burgesses, and he continued as a member through 1698. About 1700, however, he retired to England, where he spent his remaining years in relative obscurity.

Ludwell was married twice. In or before 1667 he married Lucy Higginson Bernard, the daughter of Robert and Joanne Tokesay Higginson and the widow of William Bernard. Before her marriage to Bernard, Lucy had been the widow of Major Lewis Burwell. She died in 1675. By October 1680 Ludwell had married Frances, Lady Berkeley, the widow of Sir William Berkeley and previously the widow of Samuel Stephens, the second governor of North Carolina. Frances was the daughter of Thomas and Katherine Culpeper of Feckenham Parish, Worcestershire, England, who had emigrated to Virginia with their family in 1650. She died about 1691.

Ludwell had two children who lived to maturity, a son, Philip, and a daughter, Jane. Both were born of his first marriage. Philip, Jr., like his father, was prominent in governmental affairs, serving as a member of the Virginia Council, as colonel in the militia, and in other capacities. He married Hannah Harrison, the daughter of Benjamin Harrison, and he had a son and two daughters who lived to maturity. He died in January 1726/27. Jane Ludwell married Daniel Parke, the son of Colonel Daniel Parke. She and her husband lived for a time in England and later in the Leeward Islands, where Parke was governor. She had two daughters.

During his first marriage, Ludwell lived at Fairfield plantation, also called Carter's Creek, in Gloucester County. He later moved to his brother's plantation, Rich Neck, near Williamsburg, which he inherited at Thomas's death in 1678. On his second marriage he moved to nearby Green Spring, the estate of Governor Berkeley, which had been bequeathed to Lady Berkeley.

Little is known of Ludwell's life after he retired to England. Not even the date of his death is known, although a letter dated 4 Jan. 1723/24, written to Philip, Jr., by a cousin in England, indicates that Ludwell had died recently. Ludwell was buried in the family vault in Bow Churchyard, near Stratford, in Middlesex.