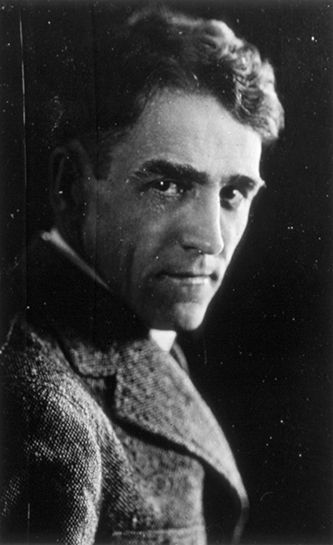

12 Sept. 1877–16 Aug. 1944

Frederick Henry Koch, university professor of dramatic art and promoter of the American folk play, was born in Covington, Ky., in a family of nine boys and one girl. His father, August William Koch, was of German ancestry; his mother, Rebecca Cornelia Julian Koch, came from French stock. August, an accountant and cashier in the Etna Life Insurance Company, was a freehand artist and inventor. His imaginative bent showed up in his children: three of his sons became architects, the daughter a singer. From his father Frederick obtained creative talents, from his mother a playful disposition.

Koch grew up in Illinois. He attended Peoria High School and Caterals Methodist College, then Ohio Wesleyan, from which he was graduated with the A.B. degree in 1900. Wishing passionately to become an actor, he spent some time at the Emerson School of Oratory in Boston, but when his family frowned on his histrionic ambition, Koch enrolled at Harvard to study English literature. Unable to stifle completely his thespian urge, however, he traveled around the countryside giving readings of Shakespeare. He was awarded the M.A. degree in 1909.

At Harvard Koch fell under the dramatic influence of George Pierce Baker who was, at the time, stirring a group of young men and women to write plays on native American subjects. After graduation, Koch took an extended trip to Greece, North Africa, Syria, Egypt, and Palestine. At Athens he met an Irish-American girl, Loretta Jean Hanigan, whom he married in 1910. They had four sons: Frederick, George, Robert, and William. From 1905 to 1918 Koch taught English at the University of North Dakota where, besides conducting courses in literature, he founded the Dakota Playmakers. The Playmakers produced one-act plays on the life of the state, written by students. The plays were trouped around North Dakota and presented to schools and communities, some of which had never before seen a dramatic performance.

Informed of the singularly productive work being done by Professor Koch in the Midwest, President Edward Kidder Graham of The University of North Carolina wished to develop similar creative activity at his institution. In 1918 he wrote to Koch and persuaded him to come to the Southeast. In Chapel Hill, Koch taught dramatic literature and playwriting for twenty-six years. Young men and women from every section of the state came to work with him, and they were soon joined by students from other states, then from abroad: Canada, England, Germany, Egypt, Korea, Japan, the Philippines, Mexico, Chile, and elsewhere. Among the dramatists, novelists, and short-story writers (authors who were inspired and guided in one way or another by the lively theater man from the Midwest) were Thomas Wolfe, Paul Green, Betty Smith, Jonathan Daniels, Noel Houston, Joseph Mitchell, Frances Gray Patton, Bernice Kelly Harris, Le Gette Blythe, Howard Richardson, and Josefina Niggli.

To provide a means for his authors to see their work in performances, Koch organized a producing group, the Carolina Playmakers, modeled on the Playmakers of North Dakota. Many of the actors, directors, dancers, and designers who received instruction at The University of North Carolina later entered the professional world of the stage, motion pictures, and television. The university group—again following the example of the Dakota students—trouped their plays all over North Carolina, and extended their tours to such far-off places as New York, Boston, Dallas, and St. Louis.

With the help of the University Extension Department and its associates, Koch established a Bureau of Community Drama, with a field secretary, which developed dramatic centers in other parts of the state. The productions of high school, college, and community groups were brought yearly to the university in Chapel Hill where they were staged in a spring Festival. Thirty years after Koch's death, the yearly Festival was still being held.

Selected student-written plays were published by Koch in five volumes: Carolina Folk Plays (in four series) and American Folk Plays. He sponsored single authors' works in Alabama Folk Plays, by Kate Porter Lewis; Folk Plays of Eastern Carolina, by Bernice Kelly Harris; and Mexican Folk Plays, by Josefina Niggli. Some of Miss Niggli's short stories were combined and issued in a motion picture, Sombrero. Outdoor historical plays, inspired by Koch and written by Paul Green and Kermit Hunter, were produced and published.

Koch used the term "folk play" in the sense of the German volk (common people), thus describing his employment of the word: "The term 'folk,' as we use it, has nothing to do with the folk play of medieval times. But rather is it concerned with folk subject matter: with the legends, superstitions, customs, environmental differences, and the vernacular of the common people. For the most part they are realistic and human; sometimes they are imaginative and poetic." The early plays of Eugene O'Neill and Paul Green, Koch regarded as folk plays; the dramas of such writers as Bernard Shaw and John Von Druten were not.

A man of remarkable energy and enthusiasm, Koch remained active until the time of his death. He was buried in the old Chapel Hill Cemetery.