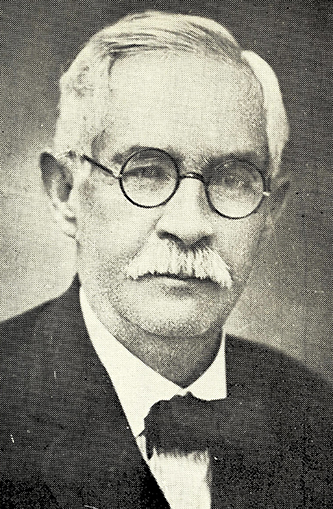

29 Aug. 1859–27 Dec. 1934

See also: Livingston Johnson, brother.

Archibald Johnson, editor, was born in what is now Spring Hill Township, Scotland County, the son of Duncan and Catherine Livingston Johnson, both of whom were of Highland Scots ancestry. He was six when the neighborhood fell directly in the path of one column of William T. Sherman's army, then driving Joseph E. Johnston north towards Durham Station for the surrender of the last Confederate army. Johnston, unable to halt Sherman, did what he could to delay him and so burnt all bridges behind him.

Duncan Johnson's house was within a mile of a bridge over the Lumber River, and it took Sherman's engineers three days to improvise a crossing; in the interim, the waiting army had time to apply Sherman's "scorched earth" policy to the neighborhood with the utmost rigor. Duncan Johnson had been a moderately affluent landowner and master of five or six "prime field hands" who, with their women and children, numbered from a dozen to a score of black people dependent on the farm. Within three days he was reduced from a man of substance, although less than wealth, to literal pauperism. Except for the house that sheltered the family, every structure on the place—barns, stables, corncrib, smokehouse, even wagon sheds—burned and all livestock and every wheeled vehicle were carried off; not even farm implements were left.

Thus early in life Archibald Johnson was acquainted with the harsh reality of the struggle for survival; if he remained relatively unscarred, it was because everyone he knew was very nearly in the same condition. Where everyone has to struggle for bare subsistence, the distinction between rich and poor vanishes; which is one, perhaps the main reason why the mature man, recognizing human excellence, never associated it with money.

Yet even in its evil days the community managed to maintain the Richmond Academy, one of those private schools that were predecessors of the modern high school system. Within its walls young Johnson acquired "little Latin and less Greek," but a respect for genuine learning that remained with him throughout life. Then, in the debates staged by the Richmond Temperance and Literary Society, he gained the knack of thinking on his feet and speaking clearly and persuasively.

But he was not cut out for a farmer. Soon after his marriage in 1885 to Flora Caroline McNeill, the youngest daughter of Hector McNeill, wartime high sheriff of Cumberland County, Johnson went into the mercantile business at Laurinburg. However, after a bout with typhoid fever kept him in bed for nine weeks, he turned to his true vocation as editor of the Laurinburg Exchange and later, for a year or two, of the Red Springs Citizen.

In 1895, John H. Mills, founder of the Thomasville Baptist Orphanage, retired and the trustees reorganized the institution. Mills, a devotee of vocational education before the term was invented, had set up a print shop, mainly to give some of the older boys an apprenticeship to the trade; from it he issued a weekly newspaper to plead the cause of the orphanage. He named the paper Charity and Children, edited it himself, and distributed it through some of the Baptist churches in the state. After his retirement, the trustees decided to divorce the paper from the routine management of the Thomasville Orphanage and to employ a professional newspaperman to edit it and also to act as field representative of the orphanage. For this they needed a person known to be able to write and speak.

After some search the trustees fixed upon Archibald Johnson, who held the job for thirty-nine years. Towards the end, failing health forced him to transfer the main burden of the work to the man who became his successor, the Reverend John Archibald McMillan, but titular editor he remained until the day of his death. The reason for the trustees' generosity was that Johnson had converted a purely propaganda sheet with a circulation of 2,000 into a journal of opinion that eventually attained a weekly circulation of 30,000 copies. It became, in the opinion of Joseph P. Caldwell, then editor of the Charlotte Observer, "the most-quoted paper in the state."

In a way, Johnson's hand was forced. The orphanage was only one of many agencies of the Baptist State Convention, whose official organ was the Biblical Recorder, published in Raleigh and the recognized newspaper of record for the denomination's affairs. The function of Charity and Children was to speak for the orphanage alone, but to do that successfully it must be read, and to be widely read it must have something of interest other than institutional news. Church news, including matters of faith and dogma, were the preserve of the Recorder, and political partisanship of course was barred. But that left open the whole range of intellectual concerns, so Johnson restricted strictly orphanage news to one of his four pages and filled the rest with anything that happened to interest him. Because he was so completely Tar Heel born and Tar Heel bred, what interested him interested a great many other North Carolinians. The paper, from being a dead loss, became an important contributor to the revenues of the orphanage.

Naturally Charity and Children was controversial, but the editor was master of the art of speaking his mind good-humoredly; thus the dissent he aroused, though frequently vigorous, was also good-humored. Once he was censured by the state legislature because, after it passed a bill that he regarded as preposterous, he remarked that the general level of intelligence of that body approximated that of a gatepost. But the censure was exclusively official, for too many of the unofficial public heartily agreed with his observation.

Johnson's outstanding service to the state, however, came in the early twenties, when the Fundamentalist revolt against science was building up to enactment of the Tennessee "monkey law" that led to the Scopes trial in 1925. Certain Fundamentalist leaders, especially in Arkansas, Texas, and Kentucky, launched a concerted attack on North Carolina Baptists for retaining as president of Wake Forest College, a Baptist school, the biologist William Louis Poteat, who had done his graduate work at Woods Hole and the University of Berlin. At the time, the Biblical Recorder was edited by Livingston Johnson, Archibald's older brother. Although decidedly conservative in matters of dogma, the Johnson brothers knew Dr. Poteat and had the highest respect for his intellectual integrity; both were persuaded that he was a far more devout Christian than many of his detractors. So it happened that as the storm roared to its farcical climax at Dayton, Tenn., the two most influential Baptist newspapers in North Carolina sturdily resisted the attacks upon Poteat.

A few years later when The University of North Carolina, in its turn, was beleaguered and the legislature seemed about to enact a duplicate of the Tennessee law, seventeen of the twenty-one Wake Forest graduates sitting in the General Assembly voted with the university men, giving them a majority with eleven votes to spare.

It would be erroneous to attribute either the successful defense of Poteat or the successful resistance to the monkey law to the Johnson brothers. But they happened to be in conspicuous positions, not as commanders but rather as buglers of the victorious forces. Nevertheless, as the Scripture says, "if the trumpet give an uncertain sound, who shall prepare himself to the battle?" Their clarions were loud and clear, and that should be their memorial.

Survived by his wife, four daughters, and a son, Archibald Johnson was buried in the old Spring Hill churchyard near Wagram.