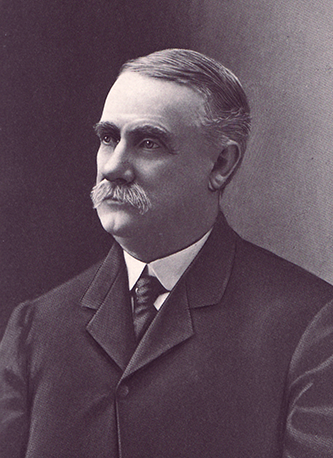

28 Sept. 1851–8 Feb. 1912

George Alexander Gray, cotton manufacturer of Gastonia, was one of a group of self-educated, self-trained engineers in the South who brought technical proficiency to cotton manufacturing. He was born in Crab Orchard Township, Mecklenburg County, the youngest of nine children of George Alexander Gray and his wife, Mary Wallace, daughter of Robert Wallace, whose parents had emigrated from Ireland. His paternal grandparents were Ransom Gray, of Mecklenburg, a soldier in the American Revolution, and Narcissa Alexander, daughter of Colonel George Alexander who moved to North Carolina from Pennsylvania before 1769. George Alexander Gray, Sr., gave up farming in 1853 and moved his family to the nearby Rock Island cotton factory. Before 29 June 1859, when he died suddenly of apoplexy, the family had settled near the Stowesville factory. The older children went to work but George, who was only eight, became his mother's companion and "special pet." She called him "Pluck" because of his self-confidence.

In 1861, at the age of nine, Gray entered the factory briefly before it closed with the outbreak of the Civil War. Mrs. Gray moved her family to Caleb John Lineberger's cotton factory at what was called "Pinhook" on the South Fork of the Catawba River. Here at the Woodlawn Mill (generally known as "Pinhook"), George worked as a sweeper boy; he was paid ten cents for a twelve- to fourteen-hour day. During his convalescence from an accident at the mill in which his arm was broken in three places, he attended school. He later wrote "I sought to master the 'Blueback' and my other books entirely within one year, for somehow or other I felt that that year's schooling would be my last."

Returning to the mill, he worked diligently to master the machinery. He assumed more and more responsibility and in time became assistant superintendent. At age nineteen he became acting superintendent of the Woodlawn Mill—at a wage of fifty cents per day. In 1878, Gray temporarily left "Pinhook" to start the first cotton mill in Charlotte when Oates Bros. & Co. engaged him to equip and operate the Charlotte Cotton Mills. Four years later, he was employed by Colonel R. Y. McAden to start a mill at McAdenville where Gray personally supervised the installation of the first system of electric lights to be used by any mill in the South.

By working in several mills and factories as a superintendent and adviser, Gray had saved enough money to open his own mill in 1888. With the assistance of Captain R. C. G. Love, Captain J. D. Moore, and John H. Craig, he organized the Gastonia Cotton Manufacturing Company, one of the first plants operated by steam in the state and the first mill constructed in Gastonia. He recognized in Gastonia, then a small village of barely three hundred people, a source of cheap fuel, abundant labor, raw material, and good transportation—factors that would make it an important center of cotton manufacturing.

Subsequently Gray was associated with the founding of nine of eleven cotton mills in Gastonia. In 1894, he built the Trenton Cotton Mills with the help of George W. Ragan and R. C. Pegram and, in 1897, the Avon Mill with John F. Love. The latter was the first mill in Gastonia to run on fine yarns and sheeting. Gray remained president of this prosperous mill until 1905. In 1899, he founded the Ozark Mill; in 1900, the Loray Mill (later called Firestone Textiles), which was the largest cotton mill under one roof in the state; and, in 1905, the Gray Manufacturing Co. of which Gray served as president, treasurer, and principal stockholder. The Clara, Holland, and Flint mills were founded in 1907. Gray was president of most of these companies. During his lifetime only two other mills were built in Gastonia without his assistance. He also helped organize the Wylie Mill at Chester, S.C.; the Scottdale at Atlanta, Ga.; and the Mandeville at Carrollton, Ga.

Gray installed the latest steam engines in each successive mill. In 1905, he operated the first electrically driven mill in the Carolina Piedmont. As soon as he was able to utilize hydroelectric power from Great Falls, he abandoned his steam-driven generator.

Noted for his upright, straightforward dealing, Gray followed a routine characterized by self-discipline and industry. From childhood on, he arose at five o'clock and started work by six. He was energetic—forming judgments and taking actions quickly, wasting little time on superfluous words. Gray enjoyed a keen sense of humor and read Shakespeare, Burns, and Moore for relaxation. He abstained from drinking and smoking while respecting the opinions of others. A devoted member of the Methodist Church in Gastonia, he made a large donation to the new church building in 1900.

Gray died in Gastonia, survived by his wife, Jennie Withers Gray, daughter of Jerry R. Withers, and eight of their ten children.