3 Jan. 1804–11 Feb. 1877

Calvin Graves, legislator, lawyer, and farmer, was born in Caswell County near Yanceyville. He was a direct seventh generation descendant of Captain Thomas Graves who arrived in Virginia from London in 1608, settled on the James River, and represented Smythe's Hundred in the Virginia House of Burgesses of 1619, the first representative legislature convened in America. His grandfather, John Graves, was the first of the family to move to North Carolina, settling in Caswell County near Country Line Creek in 1770 and serving his new state in the General Assembly and the constitutional conventions of 1788 and 1789, called to consider the ratification of the Federal Constitution. His father, Azariah Graves, was general of the Sixteenth Brigade, Third Division, of the North Carolina militia during the Revolutionary War and, for seven terms, represented Caswell County in the state senate. Calvin Graves's mother was Elizabeth Williams, daughter of Colonel John Williams, also a prominent Revolutionary War leader.

After receiving his early education at Bingham Academy near Hillsborough and other schools, Graves entered The University of North Carolina in 1823 and remained one year before withdrawing to study law under his brother-in-law, Judge Thomas Settle. He remained there a year before enrolling in the law school conducted by Judge Leonard Henderson. Graves was admitted to the North Carolina bar in 1827 at age twenty-three and began to practice in 1828.

With a Jeffersonian political heritage behind him, it is not surprising that Calvin emerged as a staunch Jacksonian Democrat. He entered political life as a delegate from Caswell County to the North Carolina Constitutional Convention of 1835, held in Raleigh. In this convention he voted against any changes in the religious tests which then prevented Roman Catholics from holding public office. Graves also opposed the continued enfranchisement of the free Black people living in the state. He supported the biennial sessions of the General Assembly and direct election of the governor by the voters for a two-year term. He also worked hard for the adoption of the proposed constitutional amendments in his home county, which were approved by a three-to-one majority.

Continuing with his law practice, Graves was first elected to the legislature as a member of the house from Caswell County in 1840, that being the first General Assembly to meet in the newly completed state capitol. He was reelected to the house and remained there through the 1844–45 session. In 1846, he was elected to the state senate where he served for two terms. As a member of the house, his leadership qualities were recognized early by his colleagues, who chose him as speaker in 1842, in only his second term. Whig control prevented his reelection as speaker during the next session. While running for the senate in 1846, he was apparently seriously considered by some members of the Democratic party leadership as a possible nominee for governor; however, he effectively removed his name from consideration as not being the "proper person" for the times. Upon his election to the senate, he was chosen as speaker pro tempore and delivered one of the more influential speeches of the session, opposing an attempt by the Whigs to engineer a mid-decade redistricting of the state for what was considered by the Democrats as political expediency. His reasoning is said to have convinced enough Whigs to change their minds so that the bill failed. In 1848, Graves was elected speaker of the senate after a week-long voting marathon caused by the successive tie votes of a deadlocked chamber. It was finally broken by a compromise that reflected the confidence in which he was held by Whigs and Democrats alike.

It was in this 1848–49 session that Calvin Graves fully revealed his qualities of statesmanship and played the part for which he is best remembered. Plagued from its very beginning by conflicting geographic features and political boundaries, North Carolina had found it difficult to reconcile the resulting economic differences—hence, the divergent political interests between the eastern and western sections of the state. With the advent of canals, and later railroads, some foresaw a means of tying the state together both economically and politically. By 1848, the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad provided the east with a north-south line to out-of-state markets, and the west wanted its own access to northern markets by the proposed Danville-Charlotte link. Some state leaders believed that the time had come to unify the state with an east-west line the proposed North Carolina Railroad. As speaker of the senate, Calvin Graves, who served a western county through which the Danville-Charlotte link would pass, was faced with the same tie vote that had earlier blocked his election as speaker. Believing that the state's only chance for real growth and development lay in economic unity, he unhesitatingly cast his tie-breaking vote for the North Carolina Railroad, which eventually connected Raleigh, Graham, Greensboro, Salisbury, and Charlotte, with a later extension to Asheville. In voting for this act he was aware that he was ensuring the future welfare of the entire state, but at a cost of personal political oblivion. He was never again elected to political office. However, some friends apparently urged him to run for Congress in the mid-1850s, whereas others petitioned him to run for the General Assembly in 1864, but he always declined.

After the 1848–49 session adjourned, Graves joined former Governor John M. Morehead, Judge Romulus M. Saunders, and John A. Gilmer in touring the state to make a public appeal for raising the private capital required to match the state appropriated funds that would make the North Carolina Railroad a reality. As a result Governor Charles Manly, North Carolina's last Whig governor, appointed Graves a commissioner on the Board of Internal Improvements in 1849; he was reappointed to the post by Democratic Governor David S. Reid and served until 1854.

Graves also pursued other interests during these early, postlegislative years. In 1844 he was appointed a trustee of The University of North Carolina and served until 1868, when the Radical Republicans took control of the government. During the 1848–49 legislative session, he supported Dorothea Dix's plea for a psychiatric hospital and was involved for some years thereafter in helping to ensure its establishment.

In 1837 he joined the Trinity Baptist Church near his home and throughout his life remained a staunch supporter of his church and his faith. His advice was sought by such men as Dr. Samuel Wait and Elder Thomas Meredith, who visited him often as they and others led the struggle to establish Wake Forest College and the Baptist paper, the Biblical Recorder. In 1844 he was elected a trustee of Wake Forest College and served until 1862. When presiding as moderator of the Beulah Baptist Association in 1857, he pledged $500 to the endowment of Wake Forest when the institution was making its first real effort in the field to create such a fund. He taught Sunday school and was very active in his home church, writing at one point that he was conducting a Sunday school class for fifty African-Americans.

In the early 1850s Graves retired from his law practice and began devoting more and more of his time to managing his farms, the use of which he had been given by his father and which he inherited upon his death. By 1856, he complained that his eyes were failing him and that, after a day's work overseeing his farms, he no longer had the strength or the desire to write letters or perform his record-keeping chores. The death of his wife Elizabeth in 1858, after a two-year illness, virtually marks the end of his active participation in public affairs. Early in 1859 he remarried and continued to live quietly on his farm until his health gradually declined in the early to mid-1870s. He died at the age of seventy-three at his home, Locust Hill, about ten miles west of Yanceyville, Caswell County. His grave is located in a family graveyard about two miles southwest of his home.

Graves has been characterized as calm, stable, and deliberate in temperament, never in a hurry, very slow to anger and thorough in all endeavors. He is said to have looked with charity upon all his fellow men. His letters abound with moral counsel and religious blessings for his relatives, and with prayers for the sustenance of his friends. He was well known as a sound source of advice, political and otherwise; his letters to political leaders reflect detailed analyses of current events.

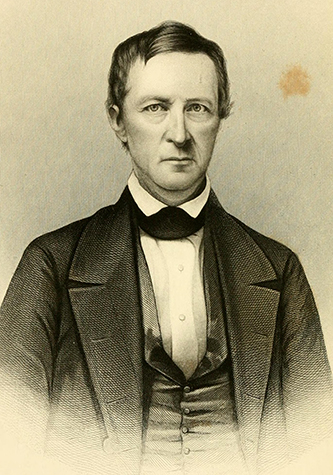

In 1830 Graves married Elizabeth Lea, daughter of John C. Lea, by whom he had four children: John Williams, a graduate of The University of North Carolina in 1854, captain in the Confederate Army, and lawyer, who died in 1872 from an illness in Salt Lake City where he was a member of the bar; George, who married and seems to have lived near his father and helped manage the farms; and two daughters, Betty and Caroline, both educated at female academies. His second wife was Mary Wilson Lea, widow of William Lea who died in 1856, and niece of his first wife. There were no children by this marriage. A portrait of Calvin Graves is published in John Livingston's Portraits of Eminent Americans Now Living, 1853–1854. Graves indicated that the daguerreotype for this engraving was made in New York about 1851 or 1852 especially for Livingston's book.