ca. 1679–1735

Christopher Gale, colonial chief justice of North Carolina, was born in York to a family that hailed from the neighborhood of Scruton, North Riding, Yorkshire, England. He was the oldest of the four sons of the Reverend Miles Gale and Margaret Stone, his wife. Three of their sons settled and died in North Carolina. Both the Gale and the Stone families were respectable gentry, the former having furnished lord mayors of York in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Gale's grandfather, Christopher Stone, was chancellor, and his first cousin once removed, the celebrated antiquarian, Thomas Gale, was the "good dean" of the archiepiscopal cathedral of York. Gale's sense of the dignity owing to his family appears to have colored his life, to have lent him a certain imperiousness, and to have affected his relationships with his peers. His thirty-five-year career may be said to have been characterized by conflicts and struggles of increasing intensity and bitterness with nearly every governor of North Carolina from shortly after Gale's arrival in the colony until his death.

Gale was presumably educated at St. Peter's School in York. He subsequently read law as an articled clerk under an unnamed Lancashire attorney. Almost immediately upon achieving his majority, he emigrated to North Carolina to seek his fortune as a trader. In order to be in the center of the Indian trade in North Carolina, Gale settled in the newly developing country south of Albemarle Sound, Bath County. His marriage in January 1702 to Sarah Laker Harvey, daughter of councillor Benjamin Laker and widow of Governor Thomas Harvey, increased Gale's working capital. By 1703 his coastal trade extended through Virginia into New England, and his Indian trade was expanded into a copartnery that was to extend as far west as the Catawba and Cherokee nations. These promising beginnings brought Gale political office under Governor Robert Daniel who was developing the Bath County area. In 1703 Gale was commissioned by Daniel as one of the justices of the supreme court of law in the colony, the General Court, and on 4 Apr. 1704 he was concurrently commissioned as attorney general for the colony. The following year saw the removal from office of Governor Daniel, who had provoked the ire of the Quakers because of his attempt to establish the Church of England in the colony and because of his licentiousness (he had abandoned his wife in Charleston in favor of his mistress and mother of his children, Martha Wainwright). He also had aroused the opposition of some of the Albemarle County leaders because of his development of Bath County.

Economic, social, and political differences between the two counties resulted in a struggle that eventually broke out into an armed conflict called Cary's Rebellion. One faction in the struggle was led by Thomas Cary and the other by William Glover, both of whom claimed the right to govern the colony. Gale's role in Cary's Rebellion is shadowy. Neither Glover nor Cary seems to have been willing to rely upon him altogether. Initially, however, Glover appears to have put his trust in Gale who was allowed to continue in his office as attorney general. Similarly, Glover commissioned Gale major of the Bath County militia in 1706 and went with him on an armed expedition against the Pamticough Indians that autumn. Although Glover bestowed on Gale the presidency of the General Court (that is, the chief justiceship) at the time he originally assumed the executive office in July 1706, Glover vacated the commission in April 1708 and gave the office to John Blount. As part of the Glover-Cary compromise of the following month, the commission was vacated once more, and Edward Moseley was created president of the court. Gale was kept off the bench for the next four years by Cary, Glover, and their successor, Governor Edward Hyde.

In fact, Gale was almost without office until the first administration of Thomas Pollock (September 1712–May 1714). Although Gale had secured for himself a commission as receiver general directly from the Lords Proprietors while in London in 1709, he appears neither to have qualified nor to have served in that office. Finally, after the Tuscarora Indian massacre of 22 Sept. 1711, Hyde trusted Gale sufficiently to send him to Charles Town as an envoy to secure military assistance from South Carolina. Gale's mission was a success, but his return to North Carolina was delayed for a few months on account of his capture by the French who held him briefly as a prisoner of war on Martinique. Taking in Charles Town again on his return from Martinique to North Carolina, Gale persuaded Lady Eliza Blake to grant him a commission naming him deputy in North Carolina to her minor son Joseph, one of the Lords Proprietors of Carolina. By July 1712 Gale was home again, and he was rewarded with a commission from Hyde that restored him to the presidency of the General Court, replacing Nathaniel Chevin who had been the first president of the court to be styled "chief justice" in the records (see the July 1711 minutes).

With this restoration, Gale's star appeared once more to be ascendant. Under authority of the deputation from Lady Blake, he took his seat on the executive council in Pollock's first administration on 12 Sept. 1712 (Hyde having died four days earlier). When Governor Charles Eden arrived and assumed the government from President Pollock on 28 May 1714, he continued Gale in his offices and entrusted him as well with the colonelcy of the Bath County militia. Despite this fair beginning, Gale was soon engaged with Eden in a bitter political quarrel. Gale was eager to strengthen the General Court and his position on it, whereas Eden was eager to strengthen the position of the governor and to increase his power. So long as the two desires remained compatible, there was no struggle between the two men.

Gale had served on the General Court from October 1703 until April 1708 and had returned to the bench in July 1712. Of those seven years, he had sat four years as president, or chief justice, of the court. During all that time it had been the practice for the governor to name six or more men in the commission of the peace erecting the court. The rule of the commission was that the first man named was the president of the court, the next two were his associate justices, and the remainder were assistant justices. The president and the two associates were justices of the quorum, without the presence of one of whom no court could be held even if every assistant justice was present. Gale sought to have this system altered. He advised that the chief justice be commissioned as such directly by the Lords Proprietors, that he alone be a justice of the quorum, and that the chief justice enjoy the prerogatives usually belonging to that officer. The commissioning of associate justices he believed should be discontinued altogether, and he felt that no more than two assistant justices should be appointed by the governor. These measures, clearly, would put the chief justice completely in control of the court and would, ideally, free the court from danger of political intrusion by the chief executive. Governor Eden looked for some such arrangement for himself, for he hoped to persuade the Lords Proprietors to authorize him to hold an executive council consisting of himself and two councillors only, rather than the usual four.

It is unclear to what extent Eden understood the full measure of Gale's ambition. In his first commission to Gale on 2 July 1714, Eden designated Gale under the style "chief justice" but appointed eight associate justices (and no assistants). Two months later, on 15 September, Eden wrote to the Lords Proprietors recommending the direct commissioning of the chief justice by their board, and requesting authority to hold an executive council consisting only of himself and two councillors. In their response of 26 Mar. 1715, the Proprietors refused Eden's request concerning the executive council but agreed to commission Gale separately. Eden appears to have felt betrayed. When Gale presented his new commission from the Proprietors and sought to qualify before the executive council on 21 Jan. 1716, Governor Eden attempted to block publication of the new commission until instructions should arrive from the Proprietary Board in London, but was overruled by the councillors. Eden, in the absence of clarifying instructions, then insisted upon the retention of ten additional justices to share the bench with Gale and issued a commission of the peace to that effect. The groundwork for a rupture was thereby completed. The rupture took place during a meeting of the executive council seven months later. On Friday, 3 Aug. 1716, while the council was in session a blowup appears to have occurred during the course of which Gale walked out of the meeting. The source of the trouble was probably the journal of the lower house of the 1715 General Assembly, which was discussed by the council on the following day in Gale's absence. The journal was found to include a set of resolves condemning certain actions of Eden's administration and appointing a committee of Bath County men to represent grievances against the governor to the Lords Proprietors. The council ruled that the resolves had never formed a part of the journal of the lower house, but had been clandestinely inserted in order to foment rebellion against Eden's government. Although Gale continued to preside as chief justice through the spring of 1717, he never attended another of Governor Eden's executive councils.

In March 1717 Gale put his affairs in order and granted a full power of attorney to his wife and four of their friends. About mid-June he set sail for England in order to appeal in person to the Lords Proprietors. It was believed in the colony at the time that Gale was in concert with Edward Moseley and the Bath County faction to remove Eden from the governorship. If so, the minutes of the Proprietary Board do not reflect it. Neither is there evidence connecting Gale with Moseley's subsequent attempt to implicate Eden in the career of the pirate Edward Teach ("Blackbeard"). Gale did appear before the Proprietary Board on 19 Feb. 1718, but he seems to have been there only on behalf of firmly establishing his concept of the office of chief justice in the minds of the Lords so as to secure it from attack in the colony. In this he was theoretically successful. The minutes of that meeting leave no doubt as to the Proprietors' concurrence in Gale's theories. The chief justice was to be supreme, not to be first among equals; he was to have no associates and only two assistants, neither of whom could act without him, though he could hold a court in their absence; the records of the General Court were to be in custody of the chief justice; and he was to have power to name his own clerk of court. By way of soothing Governor Eden, the Lords agreed to create him a Landgrave of Carolina.

Surprisingly, Gale did not return at once in triumph to North Carolina. Instead, he became distracted by Woodes Rogers and the projected expedition against the pirates in the Bahamas. Rogers offered Gale a commission as chief justice of the Bahamas (subsequently approved by royal warrant on 31 Jan. 1719) which Gale accepted; presumably he sailed for New Providence in company with Governor Rogers in July 1718. In October of that year Rogers appointed Gale to the Bahamian executive council, and, according to the contemporary Oldmixon, Gale served as register to the colony as well. How much actual service Gale saw in these offices is unclear, for he spent a good deal of his time in Charles Town. It was from there that he wrote an account to Colonel Thomas Pitts on 4 Nov. 1718 of the pirates then bottling up the Charles Town harbor. A year later he was in Charles Town again, at which time (October 1719), he wrote the account of the Spanish plan to invade South Carolina that was used by the anti-Proprietary faction in that colony to consolidate public opinion against the Lords. Gale's November 1719 letters to James Craggs, secretary of state for the Southern Department (who had come to trust Gale implicitly in Bahamian affairs), gave assurances of South Carolina's loyalty to the Crown and conveyed the colony's wishes to be taken under the direct protection of the king. These actions on the part of Gale very probably aided the South Carolinians in their successful revolt against the Lords Proprietors.

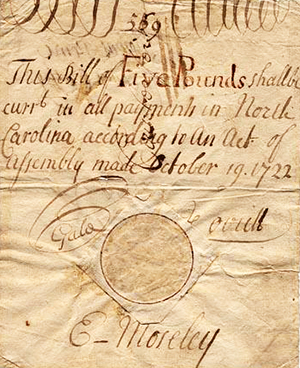

It was presumably at this time that Gale sat in his Bahamian judicials for his pastel portrait by Henrietta Johnston, widow of the bishop of London's late commissary in Charleston. From here he went home to his family in North Carolina for a visit that lasted from the 1719 Christmas holidays until midsummer 1720. On 23 Feb. 1720 he wrote an account of the South Carolina revolution at the request of Governor Eden and his executive council. Gale executed another power of attorney on 1 June 1720, this time empowering his brother Edmond, his wife Sarah, and his son Miles to act for him, and acknowledged it before Eden on 10 June.

By this time the Bahamian adventure was clearly coming to an end. In the early days of the experiment, Gale had entertained the notion of removing his family, stock, and capital from North Carolina and beginning anew in the Bahamas. The Indian wars of 1711–15 had destroyed the Tuscarora nation on whom a successful Indian trade had depended, and with the loss of that trade there was little to tempt Gale to remain in Bath County. In fact, it is clear from his dispatches that Woodes Rogers had expected a large number of Carolinians to settle in the Bahamas. Upon reflection, Gale did not make such a move. He determined instead to remove from Bath to Albemarle County. On 21 Mar. 1721 the Lords Proprietors issued a new commission to Gale as chief justice of North Carolina, and Crown officials vacated his Bahamian commission on 19 Aug. 1721. Shortly thereafter, Gale was in his new residence at Edenton (of which town he was made one of the commissioners in 1722). He was almost immediately involved in a matter that led to a course of events that haunted the remainder of his life and touched him both in name and fame.

The Christmas holiday of 1721 was Governor Eden's last one. Fatally ill, he had house guests to help him keep the season. Henry Clayton, Gale's son-in-law, was one. William Badham, Gale's old clerk of the General Court, and his wife Mary were included. John Lovick, secretary of the province, was the principal guest. Christopher Gale may have been no more than a calling guest. The house guests arrived on Christmas Eve. On Christmas Day the subject of Governor Eden's last will and testament was discussed. On St. Stephen's Day, John Lovick wrote the governor's will, which was then signed by Eden and witnessed by the house guests, Clayton and Mr. and Mrs. Badham. The only relative named in the will was Eden's niece, Margaret Pugh, who was to receive £500 sterling. Four friends were left smaller bequests (one of them subsequently revoked by codicil). The residuary legatee was John Lovick. The will mentioned neither Governor Eden's stepchildren, Penelope Galland Maule and John Galland (both of whom lived in the colony) nor any relative in England other than the niece. Eden died on 26 Mar. 1722. The will was proved before Gale on either 2 April (Lovick's endorsement date on the record copy of the will) or 9 April (Badham's note in the General Court minutes), and Lovick immediately put himself in possession of the estate.

With the death of Eden, Gale reentered the government. On 27 Mar. 1722 he assumed the office of chief justice by virtue of his 1721 commission. Three days later he presented that old 1712 deputation from Lady Blake and was seated on the council on the strength of it despite the fact that at least three of the councillors had been present when that deputation had been vacated in favor of Frederick Jones more than five years earlier. Gale was able to regularize his position on the council very shortly, however, for on 14 June 1722 he presented a deputation from another of the Lords Proprietors, James Bertie. From this point Gale's career went along almost without untoward incident through the presidencies of Thomas Pollock and William Reed. It was not until the autumn of 1723 that he felt the earth give slightly under his feet. There was every indication that Governor Eden's heirs-at-law were going to make an issue of the will and the circumstances under which it was written. On 21 Nov. 1723 Lovick petitioned the council to permit the testimonies of Clayton, Gale, and the Badhams to be made a part of the council record, which was accordingly allowed. After that, it was a matter of waiting for the heirs-at-law to make their move against the will and its principal legatee.

When George Burrington qualified as governor of North Carolina on 15 Jan. 1724, gossip about the circumstances of the Eden will may already have been current in the colony. Gale later testified that Burrington's enmity toward him dated from the new governor's first month in the colony. Perhaps this was so, but the contrary is suggested by the records. Burrington's temperament was not that of a man who would willingly surround himself with known enemies, let alone put into their hands the complete administration of justice in the colony he governed. One of Burrington's first acts was to make Gale's son-in-law, Henry Clayton, the provincial provost marshal. The other son-in-law, William Little, was created attorney general by Burrington on 2 Apr. 1724, the same day he accepted Gale on his council. A week later the governor commissioned Gale's brother Edmond as one of the two assistant justices of the General Court. Gale's old clerk, William Badham, had been restored to his office in the court by Gale two years previously. It is hard to believe that Burrington was envenomed against Gale at this time.

The rage broke out a few months later. Toward the end of July 1724 Burrington received a petition asking him to grant redress in his capacity as ordinary of the colony. The petition was from Eden's niece, Margaret Pugh, and Ann and Roderick Lloyd. They denounced the will said to be Eden's as a fraud and alleged that Lovick had obtained it illegally. On 31 July, Burrington carried the petition to a meeting of the council that was attended by both Lovick and Gale. The governor explained that the council would proceed in the matter as a Court of Ordinary. An order-in-council was issued requiring the recordation of the London petition and power in the records of the General Court. (The court was then in session.) It must have been an exhilarating occasion. To have proceeded in the matter would have meant an examination and scrutiny of Lovick, Clayton, the Badhams, and possibly Gale himself.

Gale refused to give his clerk Badham the order necessary for the recordation required by the order-in-council. Burrington exploded in rage and suspected the very worst of the entire lot. In his anger he threatened to ruin Mr. and Mrs. Badham and declared that he would have Lovick and Gale in irons. In fact, he announced his intention to crop Gale's ears and slit his nose like a common felon. In his initial burst of fury, Burrington had entered the General Court and denounced Gale on the bench as a rogue and a villain. The outraged Burrington did not cool off until he discovered during a nighttime attack on Gale's house in August that Gale had left Edenton.

Gale had not only left Edenton, but he had also left the colony. Burrington and the council declared Gale's offices vacant on 24 Oct. 1724 and filled his seat on the council as well as the office of chief justice. Gale's son-in-law Henry Clayton was dismissed as provost marshal, his brother Edmund was turned off the General Court, and after the October term Badham was replaced as clerk of the court by Samuel Swann. On 29 Oct. 1724 Lovick, through his attorney William Little, made an answer to the petition of Eden's English heirs in which he denied all their allegations. In response to the replication of the heirs, the council admitted itself powerless to oblige Lovick to give security for the Eden estate, valued by the petitioners at £8,000 sterling. Here the matter was to rest for half a year.

In leaving the colony, Gale had gone posthaste to London armed with depositions against Burrington from allies on the council. That Gale had a powerful friend and protector on the Proprietary Board is obvious, but the identity of this person is unknown. Gale easily effected the removal of Burrington by the Lords Proprietors. In the summer of 1725, almost a year after the crisis over the Eden will had erupted, Gale arrived back in Edenton, leading the newly appointed governor of North Carolina, Sir Richard Everard, who was promptly characterized by Burrington as a noodle.

The peremptory removal of Burrington ended any real threat from Eden's English heirs. The heirs petitioned the Court of Chancery for relief in April 1725, Burrington presiding; their bill was thrown out in July 1725, Sir Richard presiding, when the death of one of the plaintiffs was falsely suggested. The bishop of St. Asaph joined the cause of the heirs-at-law and appealed directly to the Lords Proprietors in March 1726. The Proprietors took no action other than to assure the bishop that they had received an account of the proceedings relating to Eden's will and that he could have a copy of the account upon application to their secretary. Stalemated by the Proprietary Board, the bishop introduced the bill of complaint once more in the Court of Chancery in July 1726, Sir Richard still presiding, and the bill was again thrown out on the grounds that the power of attorney from the heirs to Robert Lloyd and Edmond Porter had not been sufficiently proved. No more was heard from the English heirs after this. The two stepchildren in the colony did not make an issue of the will. Eden's stepdaughter, Penelope Galland Maule, was widowed early in 1726 and Lovick very quickly married her. After the marriage Penelope and Lovick gave Eden's stepson, John Galland, the ferry slip near the plantation of Mount Gallant, and Gale's son-in-law, William Little, "for love and affection" gave Galland the ferryboat that went with it. Even with this, Lovick never felt perfectly secure in the estate left by Eden. His dying instructions to his wife were never to pay a penny from the Eden estate to the heirs in England, and to ensure her compliance he made Christopher Gale, Edmund Gale, and William Little executors of Governor Eden's will upon his own demise.

In a letter to Lord Carteret (who was very probably Gale's powerful friend and protector), Burrington traced his difficulties and the upheaval in the colony directly back to the matter of the Eden will. Certainly, the Eden will was not the cause of the ideological and political difference in the province, but there can be little doubt that the controversy over it influenced political alignments and precipitated a quarrel that permanently marked Gale's career and reputation.

There had been political divisions and struggles in the colony before now, but none of them equaled the fight that arose upon the removal of Burrington and the substitution of Sir Richard Everard as governor. Gale resumed his seat as chief justice, Little was restored as attorney general, and Gale gave back to Badham his old office as clerk of the General Court. For a time the coalition of Everard, Lovick, Gale, and Little ruled the colony. The General Court became first a political tool in the hands of Gale and his faction, then an object of contempt in the province. Similarly, the Court of Vice-Admiralty in the hands of Edmond Porter (who had been one of the attorneys for Eden's heirs-at-law) became a tool of political opposition against Gale's faction. The responsibility for the jurisdictional fight that broke out between the two courts must be shared in large part by Gale. Waiving all considerations of the deleterious effects on impartial justice that were bound to arise from such a contest, he was foolish to have undertaken the political risk of pitting the Proprietary common law court against the Crown maritime court. The Court of Vice-Admiralty was bound to win such a struggle, and it did. Governor Everard fell out with Gale in the summer of 1728 after the governor was presented by the grand jury for assaulting one of Gale's friends, and Lovick was presented for assaulting Sir Richard. From that time Everard issued writs of nolle prosequi against criminal indictments brought for political purposes in the General Court and began to take the side of Edmond Porter and the Court of Vice-Admiralty. Thus the maritime court gained the upper hand. Porter's use of the Vice-Admiralty Court as a political weapon was far more unscrupulous and less subtle than Gale's similar use of the General Court. Porter aimed for nothing less than the destruction of the General Court. The province was treated to the spectacle of first the attorney general, then the chief justice, briefly in jail at Edenton by order of the judge of the Court of Vice-Admiralty.

In 1729 the sale of North Carolina and South Carolina to the Crown by the Lords Proprietors was completed. Upon the sale, many held that Gale's commission from the Lords as chief justice was no longer in effect. Gale continued to style himself chief justice through December 1730 and to hold terms of the General Court through April 1730, but less and less business was effectively handled there. By the time the newly appointed George Burrington took up the reins of government as North Carolina's first royal governor early in 1731, the General Court had been wrecked and the former chief justice had left the colony.

When Gale made his last visit to England in 1731, it was very much doubted that he would ever return to North Carolina. The fears proved to be groundless. The voyage was a business and pleasure trip, not a flight. Part of Gale's visit was spent with his kinsmen. Otherwise he attended to business on behalf of the colony. In July he attended a meeting of the Board of Trade and presented a memorial intended to assist tobacco planters in Albemarle County. In November he attended the meeting of the Privy Council at which recent charges against Governor Burrington were aired. Then Gale quietly moved behind the scenes to come to Burrington's assistance despite their old troubles. While in the capital, Gale discussed conditions in the colony with the bishop of London, and he addressed the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel on the need to send missionaries to North Carolina. It is doubtful that he much busied himself on his own account. For some years he had been one of the collectors of His Majesty's Customs in North Carolina, first at Port Beaufort (1722–23), then at Port Currituck (1723–25), and after July 1725 at Port Roanoke. When Gale returned to North Carolina in the spring of 1732, he returned in the same office he held when he left—collector of Port Roanoke. He remained collector of this port for the rest of his life; he never sat again as chief justice.

Whatever his role in the matter of Eden's will, regardless of whether the will was fraudulent or not, and despite the result of the chain of events that was set off by the threat of an inquiry into the circumstances under which the will had been written, Gale's contribution to North Carolina was enormous. The unfortunate politicization of the administration of justice during the last four years of his chief justiceship wrecked the General Court, but did not destroy it. His basic conception of the court and the role of the chief justice in it was a valid one, and his lifework was to realize the concept. Though it continued to be debated beyond his death, Gale's theory proved finally to be the model upon which the court was based throughout the colonial period. Clearly imperious and perhaps occasionally inequitable in his orders, Gale was careful to hold himself within the bounds of the law in his administration of the court. We may assume that he was as legally scrupulous in his other offices. When William Byrd of Westover charges that Gale, as one of the commissioners to determine the North Carolina-Virginia boundary in 1729, abused his appointment by attempting to enrich himself by landgrabbing, we can conclude that Byrd is speaking out of animosity rather than from fact. We may also rest assured that the abuse of blank land patents bearing his signature with others of the council during the years 1729 and 1730 took place without his knowledge or consent.

Brought up as he was in the shadow of York Minster, Gale was an active Anglican who sought to establish and nourish the established church in North Carolina. His first wife, Sarah Laker Harvey, and mother of his children Miles, Penelope, and Elizabeth, died about 1730. He then married Sarah Isabella Ismay, widow of his friend John Ismay, about 1733. In his will, written in 1734, Gale gave back to his widow the property that she had brought into the marriage; otherwise everything he owned was left to his children, granddaughter, and nephews. One bequest bears quotation: "To All my friends I leave my hearty prayers & Good wishes, To my Enemys forgiveness & prayers for their Repentance for the many ill offices done me." The Henrietta Johnston pastel portrait of Gale is owned by the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Winston-Salem.