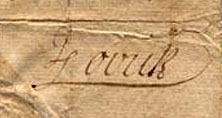

d. 2 Nov. 1733

See also: Lovick, Thomas

John Lovick, colonial official, entered North Carolina early in 1713 in the company of Governor Edward Hyde. William Byrd, in his Secret History of the Dividing Line, noted that Lovick had been Hyde's valet. Byrd described Lovick as a merry, good humored man and probably was referring to his profession when he called him "Shoebrush" in the Secret History.

Whatever his origins, Lovick made a sizable place for himself in North Carolina politics and society. At some time around 1720, Governor Charles Eden appointed him to the Proprietary Council, where he also served broken terms during the administrations of George Burrington and Sir Richard Everard (1723–25). Lovick was a delegate in the lower house of the General Assembly in 1731 and secretary of the province in 1719, 1721–23, and 1729. During the latter year he estimated his annual income from the office to be £582. Among other appointments he held in the Proprietary years were those of vice-admiralty court judge (1722) and boundary commissioner with the Virginia survey (1728).

By far the most interesting facet of Lovick's career revolved around his relationship with George Burrington while the latter was royal governor. As late as August 1729, Burrington numbered Lovick among his enemies. However, because of Lovick's own efforts as well as Sir Richard Everard's complaints about his former secretary, Burrington began to change his opinion. On 26 July 1731, he named Lovick to the royal Council as part of his strategy to expel Edmund Porter from that body. Lovick soon became the governor's closest ally and consistently voted as Burrington desired. Burrington later justified his appointment of Lovick to the Council by praising his services as a legislator and his extensive knowledge of Indian affairs.

In 1732 Lovick became embroiled in a series of events growing out of attempts by certain officials to blunt Burrington's power. For a brief period that year the governor made his ally both chief justice and surveyor general of the colony. The former appointment particularly nettled Burrington's opponents, who argued that Lovick was unskilled in the law. By early 1733 the governor was openly praising Lovick as his best councillor and the only person who could effectively convey executive concerns to the lower house.

When Lovick died, Burrington's already deteriorating relations with the General Assembly worsened. Lovick had written a will in 1727 naming Richard Everard as one of his beneficiaries. On his deathbed, however, he declared his wish that all of his property pass to his wife, the former Penelope Galland. Although Lovick had listed two plantations in Chowan County and several people whom he enslaved in his 1727 will, Burrington stated in 1734 that he had died heavily in debt. Lovick had no children, but his brother Thomas continued a long service in the colonial government.