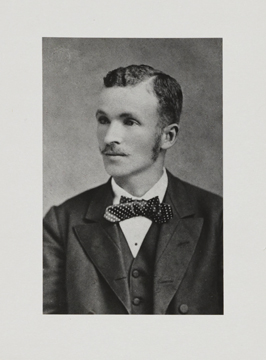

20 June 1858–15 Nov. 1932

Charles Waddell Chesnutt, writer, was born in Cleveland, Ohio, the first child of Andrew Jackson Chesnutt and his wife, Ann Maria Sampson, both of whom were born in freedom in North Carolina. During the Civil War, Andrew Jackson Chesnutt served as a teamster in the Union Army, but when the fighting ended he returned to his home in Fayetteville to become a grocer. Charles and his mother followed in 1866. Charles spent the next seven years in Fayetteville working part-time in his father's store and studying diligently in the Howard School, an institution established by the Freedman's Bureau.

At the age of fifteen, Chesnutt went to Charlotte, where he became assistant to the principal of a school. His formal education curtailed, he embarked on a program of private instruction and extensive reading in ancient and modern languages, mathematics, music, and English literature. Leaving Charlotte in 1877, he returned to Fayetteville as first assistant to the principal of the recently opened State Colored Normal School. At the age of twenty-two he was appointed principal of the school, a post he held for three years.

In 1883, he left the South for New York, having taught himself stenography as preparation for a new career in the North. For six months he worked as a Wall Street reporter, contributing a daily column of stock market gossip to the New York Mail and Express. Later that year he moved to Cleveland, Ohio, where he secured a position in the accounting department of the Nickel Plate Railroad Company. Here he began studying law and writing his first stories and sketches. After passing the Ohio state bar in March 1887, he launched a successful business career in Cleveland as a court reporter, stenographer, and attorney.

With his wife, Susan Perry Chesnutt, a Fayetteville native, he raised four children, all of whom were college graduates: Ethel and Helen (Smith College), Edwin (Harvard University), and Dorothy (Western Reserve University). Although he traveled widely in the South and Northeast and made two trips to Europe, Chesnutt never again moved his residence from the city of his birth. He died and was buried in Cleveland.

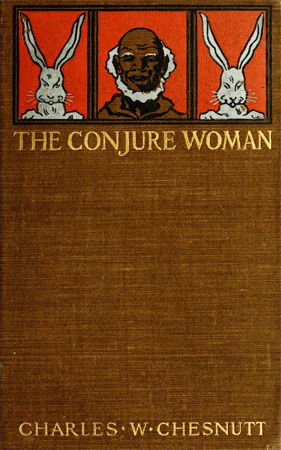

As early as 1880, Chesnutt began to think seriously in his private journal about writing a book that would combat what he called "the unjust spirit of caste" in the United States. However, his literary career began with the publication of short stories, the first of which appeared in April 1885 in the S. S. McClure newspaper syndicate. Drawing upon his experiences in New York and his memories of life in the Sandhills region of North Carolina, Chesnutt wrote a number of humorous and pathetic sketches between 1885 and 1889. But his unusual treatment of the superstitions of enslaved people in a story called "The Goophered Grapevine" caught the attention of the editors of the Atlantic Monthly. When they published the story in August 1887, it became the first work by an African American to appear in that prestigious literary magazine. Subsequent "conjure stories" were accepted by the Atlantic and Overland monthlies. At the urging of Walter Hines Page, editor of the Atlantic, Chesnutt submitted to Houghton, Mifflin and Company a collection of these stories that was published in March 1899 as The Conjure Woman. These dialect tales, which focus on the life of the ordinary enslaved people in central North Carolina, show Chesnutt's familiarity with the "plantation school" of southern writing and his skill as a transcriber of southern local color.

During the 1890s, Chesnutt was praised by a number of famous writers and critics, among them George W. Cable, James Lane Allen, and William Dean Howells, for his achievements as a short story writer. His second collection of short fiction, The Wife of His Youth and Other Stories of the Color Line (1899), ranged over subjects and themes no previous literary delineator of Black American life had attempted to portray. The note of protest against racial discrimination was present in several of the stories, but Howells was impressed with the artist's control over his materials and tone throughout the volume. The book was popular enough to convince Houghton, Mifflin to publish Chesnutt's first novel, The House behind the Cedars, in 1900. A story of the attempts of two young African Americans to pass for white in the postwar South, the novel was Chesnutt's most carefully wrought and evenly balanced long story. Like all three of his novels, it was set in the Cape Fear region of North Carolina. Chesnutt's second novel, The Marrow of Tradition (1901), drew upon an incident of North Carolina history, the Wilmington Coup of 1898, for its main action and central theme. The fiercely partisan tone of the novel convinced many reviewers that the book was an unreliable or even anti-white account of contemporary southern affairs. The book's failure to sell widely forced Chesnutt to give up his two-year-long effort to support his family on the emoluments of professional authorship. In 1905, his business affairs claiming most of his time once again, Chesnutt published his last novel, The Colonel's Dream, a story of an idealist's endeavor to revive a depressed southern town through the methods and influence of benevolent capitalism. The book received little critical notice.

Except for an infrequent short story, Chesnutt confined his literary labors after 1905 to articles, essays, and speeches, most of which dealt with the race problem in America. A friend of and correspondent with Booker T. Washington, Chesnutt nevertheless chided the Tuskegeean for his failure to argue vigorously enough for Black political rights throughout the United States. Engaged in this cause as much as his time and health would permit, Chesnutt saw his literary reputation wane as the writers of the Harlem Renaissance, espousing new subjects and new standards for African American fiction, gained preeminence in the 1920s. In 1928, however, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People acknowledged his "pioneer work as a literary artist depicting the life and struggles of Americans of Negro descent" by awarding him the Spingarn Medal. Since his death, literary critics have assigned him the first rank among all Black fiction writers of his day and an honored place in the history of southern literature. Of his six books, only the biography Frederick Douglass (Boston, 1899) has not been reprinted in a modern paperback edition.