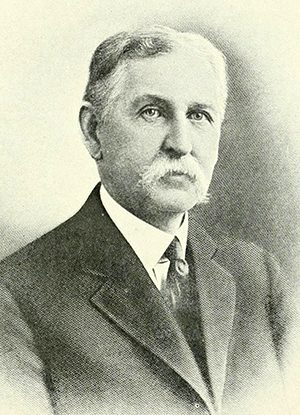

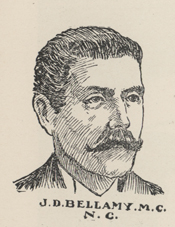

24 Mar. 1854–25 Sept. 1942

John Dillard Bellamy was a congressman, legislator, attorney, manufacturer, and a Red Shirt and 1898 Wilmington Coup conspirator. Bellamy was born in Wilmington, the son of Dr. John Dillard Bellamy and Eliza McIlhenny Harriss. He was educated under George W. Jewett at the Cape Fear Military Academy and graduated from Davidson College in 1873. After receiving a degree in law from the University of Virginia in 1875, he began the practice of law in Wilmington, where he soon became the city attorney. He served in the North Carolina Senate in 1891–92 and in Congress from 1899 to 1903. He was counsel for the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad and afterwards for the Seaboard Air Line Railway. He established and was the principal owner of the Wilmington Street Railway for a number of years, until it was electrified. He was president of the North Carolina Terminal Company; president and owner with his son-in-law, J. Walter Williamson, of the Bellwill Cotton Mills; largest stockholder of the Delgado Cotton Mills; and the largest local owner of the capital stock of the Carolina Insurance Company.

Bellamy was an active Democrat, and was also an important figure in the Wilmington Coup and Red Shirts campaigns of 1898. Until the coup in 1898, Wilmington’s multiracial Fusion politics, businesses, and social structure were generally successful. As North Carolina’s then-largest city, the election of 1898 was a target of white supremacist media and activists across the state to undo the progress made for black Americans under the Fusion-Republican coalition. Written and spoken messaging, as well as voter intimidation, coercion, and fraud from the Red Shirts, were all used to sway the electorate to support white supremacist Democrats in the election cycle. Bellamy was elected to the United States Congress as a Democrat during the 1898 election cycle in Wilmington with the aid of the Red Shirts. Bellamy aided voter intimidation and misinformation schemes before and during the election in Wilmington by claiming that black people that sought to vote in the election were “dangerous” and “were prone to carry weapons.” He also claimed that all black voters “constantly carry concealed weapons… the razor, the pistol, the slingshot, and the brass knuckle seem to be their inseparable accompaniments as a class.” The claim that black voters were armed and dangerous was a proponent of the spoken and written messaging aimed at intimidating and riling white voters to support white supremacist candidates; this messaging also threatened black voters away from polling places.

Bellamy was also directly involved with the Red Shirts in addition to perpetuating dishonest messaging about black voters in North Carolina. During election day on November 8th, numerous black voters in Wilmington still voted despite the messaging being used to dissuade them from doing so. One group of Red Shirts wanted to further dissuade black voting and sought to lynch Alex Manly. Manly was the editor of the Wilmington Daily Record, the newspaper which published an article in August 1898 destigmatizing interracial relationships and became a target for white supremacist attack messaging. This group of Red Shirts was welcomed and “enjoyed a drink” at the office of John D. Bellamy during their planning of the postponed attack. On November 9th, a newly-elected Bellamy addressed a group of white supremacists that sought to lynch Alex Manly for his publication on interracial relationships. While dissuading lynching, Bellamy supported punitive measures for Manly’s publication. This directly opposed the 1st Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which protected freedom of the press and publication from punitive legal measures and legislative action. When learning that Manly had fled Wilmington before the election, Bellamy proclaimed that “Wilmington has been rid of the vilest slanderer in North Carolina." According to a letter written by a black citizen of Wilmington on November 13th, 1898, Bellamy was also identified as one of the leaders of the street mob that destroyed much of the black infrastructure and property in Wilmington on November 10th. The letter was written as a plea to President McKinley for help, and Bellamy's involvement in the attack on Wilmington is implicated throughout by the author.

Bellamy served as the representative of the Wilmington seat until 1902. After being unsuccessful as a candidate for re-nomination in 1902 to the Fifty-eighth Congress, he resumed the practice of law in Wilmington, N.C. He was also a delegate to the national conventions of 1892, 1908, and 1920. He was a delegate to the Washington Disarmament Conference in 1924 and in 1932 was the commissioner from North Carolina to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the birth of George Washington. In 1936 he was selected to cast the electoral vote of North Carolina for Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Bellamy was grand master of the State of North Carolina of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows in 1892 and representative to the sovereign grand lodge of that order for the two following years. He was the author of Address on the Life and Services of General Alexander Lillington (Washington, 1905), Sketches of the Bar of the Lower Cape Fear (Raleigh, 1925), Memoirs of an Octogenarian (Charlotte, 1942), and Sketch of Maj. Gen. Robert Howe of the American Revolution (Wilmington, 1882).

Bellamy was a Presbyterian. He married Emma Mary Hargrove, daughter of Colonel John and Mary Grist Hargrove, in 1876. Their children were Mrs. James Walter Williamson, William McKoy, Emmett Hargrove, Mrs. J. Leeds Barroll, Jr., and Mrs. Nelson McRae.

Bellamy was buried in Oakdale Cemetery, Wilmington.