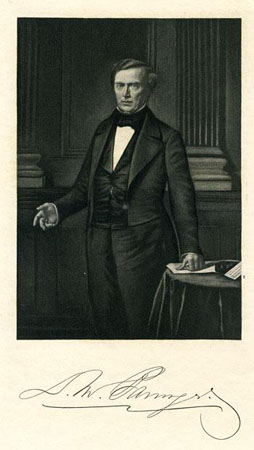

30 July 1806–1 Sept. 1873

Daniel Moreau Barringer, lawyer, congressman, and minister to Spain, was born at Poplar Grove in Cabarrus County, the oldest child of Paul Barringer and Elizabeth Brandon and the grandson of John Paul Barringer, a German immigrant who became a prominent citizen of Cabarrus County. His uncle was congressman Daniel Laurens Barringer, and his brothers were Rufus and Victor Clay Barringer. He signed his name Daniel M. or, more often, D. M., but he was called Moreau by family and friends.

Barringer was prepared for college by the Reverend John Robinson of Cabarrus County; he enrolled at The University of North Carolina in January 1824 with advanced standing, entering the second term of the sophomore year. After graduation as an honor student in June 1826, he remained at the university for a few months, after which he began the study of law in Hillsborough with Thomas Ruffin. He was admitted to the bar early in 1829 and began practice in Concord in his home county, speedily attaining success in his profession.

Barringer was elected to the House of Commons in 1829 and in the six succeeding annual elections. He was active as a committee member and served as chairman of the Committee on the Judiciary. In the session of 1834–35 he was a member of two successive committees on a bill to provide for amending the state constitution, a measure that he and other representatives of western counties had been advocating for some time. The reform movement resulted in the call of the constitutional convention of 1835. Barringer again represented his county and served as a member of important committees, but illness led him to request leave of absence before the convention adjourned. He went immediately to Philadelphia for medical treatment, but his recovery was so slow that for several years he refrained from public activity. In 1840 and 1842 he returned to the legislature, which then met biennially.

In 1843, Barringer ran for Congress in a district formerly represented by a Democrat and won by more than 350 votes after a hard campaign. He was reelected in 1845, defeating veteran Democratic politician Charles Fisher by a narrow margin. In his third election, in 1847, no candidate was nominated in opposition to him. He was an early and active supporter of Zachary Taylor's 1848 presidential campaign, but he did not run for reelection to Congress. Instead, he sought a diplomatic appointment, soliciting the post of minister to Spain in spite of the opposition of the North Carolina senators, who, though both Whigs, were supporting other candidates. Barringer was appointed on 18 June 1849, spent some time in Washington for briefing, and reached Madrid in time for presentation to Queen Isabella II on 24 Oct. 1849. Confirmation of his appointment was delayed until September 1850, through the influence of one of the disgruntled North Carolina senators.

Unlike the preceding and succeeding Democratic administrations, the Whig administration of Taylor and his successor Fillmore, who reappointed Barringer, made no effort to acquire Cuba from Spain. Barringer was instructed instead to seek adjustment of the discriminatory customs duties and other restrictions on the trade of the United States with Cuba and Puerto Rico. Such peaceful aims were hampered by the strained relations that resulted from several filibustering expeditions to Cuba, launched from the United States by Narciso Lopez and other refugee Spaniards, with the support and participation of American citizens. The first expedition was prevented from sailing by the federal government, but two more reached Cuba and were defeated there. Prisoners were taken both times, and, after the second defeat, Lopez and a number of others were executed. Receipt in New Orleans of news of the execution of several Americans precipitated an anti-Spanish riot and the wrecking of the Spanish consulate. The surviving captives were sent to prison in Spain, where many appealed to Barringer for aid. He was diligent in his efforts in their behalf, even though he did not approve of the expeditions and doubted that all of the claims to American citizenship were valid. The State Department in Washington and Barringer in Spain worked to maintain peaceful relations, to resist threatened guarantees of Spanish possession of Cuba by Great Britain and France, and to procure the release of the prisoners. They were ultimately successful in these aims, although the pardon of the prisoners was delayed until Congress voted reparations for the wrecking of the consulate in New Orleans. In spite of the problems related to Cuba that dominated his ministry, Barringer managed to maintain cordial personal relationships in Spain, where he and his attractive young wife were popular in diplomatic and court circles.

Mrs. Barringer was the former Elizabeth Wethered, daughter of Lewin Wethered, prominent Quaker merchant of Baltimore, and sister of former Whig congressman John Wethered. She and Barringer were married on 15 Aug. 1848, when Barringer was forty-two and she was twenty-six. In the interval between their marriage and the departure for Spain, they did not establish a residence, and they were slow to do so when Barringer's ministry ended. He was not replaced immediately by the Democratic administration of Franklin Pierce, but he resigned and left Spain in September 1853, traveling in Europe with his wife and two young children, who had been born in Spain, before returning to the United States in May 1854. Mrs. Barringer spent much of the time in the next few years with her family in Baltimore, while Barringer went back and forth between Baltimore and North Carolina. They usually spent summers at watering places in Virginia.

Barringer renewed his political connections in Cabarrus County immediately on his return and was again elected to the House of Commons for the session of 1854–55. He was nominated for election to the U.S. Senate, but the Whig party was declining and a Democrat was elected. Perhaps because of the party situation, perhaps because of his unsettled residence, Barringer did not serve again in the legislature. He opposed the principles of the American party and in 1856 affiliated with the Democrats.

Barringer's inheritance from his father, including lands in Mississippi, and the successful investment of the proceeds of his early law practice, furnished ample means for a comfortable life. When he established residence in Raleigh in 1858, he became a member of the Raleigh bar but did not engage in active practice. He bought and renovated a home near the governor's "palace," and he and his wife became prominent Raleigh residents. Barringer was busy with service on the board of trustees of The University of North Carolina, the board of directors of the North Carolina Railroad, and other public affairs, but did not seek elective office. The Buchanan administration offered him appointment as minister to Costa Rica and Nicaragua, but he declined. By 1860 he had become a leader in the Democratic party and a member of the state executive committee. He and Lincoln had been fellow-Whigs in the Thirtieth Congress, and, according to family tradition, had been seat mates and friends, but in 1860 Barringer urged North Carolina Democrats to agree on one slate of electors pledged to vote for the Democratic candidate most likely to defeat Lincoln. When his efforts to unite the two opposing factions of the party failed, he supported the Breckinridge-Lane ticket. After the election, he was chosen by the legislature to be a member of North Carolina's delegation to the 1861 Peace Convention in Washington and served conscientiously, despite his doubt that the body could reconcile conflicting viewpoints. When North Carolina seceded, he supported his friend Governor John W. Ellis. In 1862 he was appointed an aide, with the rank of colonel, to Ellis's successor, Henry T. Clark.

For the remainder of the war years, Barringer and his family lived quietly in Raleigh, saddened by the enforced separation from Mrs. Barringer's family in Baltimore and grief-stricken by the deaths in 1864 of two children. In March 1865, Barringer fell while dismounting from a railroad car in Salisbury and sustained a badly broken leg, which recovered slowly and remained permanently shortened. Investment in Confederate, state, and railroad stocks and bonds caused heavy losses, but Barringer's financial circumstances at the end of the war still compared favorably with those of most North Carolinians. New grief came, however, when Mrs. Barringer developed cancer in 1866. She went for treatment first to Baltimore and then to New York, where she died on 4 June 1867 after prolonged illness. Barringer's chief concern thereafter became the care and education of the remaining children, one a boy only seven years old.

Despite family anxieties, Barringer did not entirely lose interest in politics. He was a delegate to the Union Convention in Philadelphia in 1866, and in April 1867, in a letter widely published in the newspapers, he urged cooperation with congressional Reconstruction. By 1868, however, he was actively supporting the Conservative presidential campaign. In 1872 he was a delegate to the Baltimore convention of the Democratic party and chairman of the state Democratic-Conservative executive committee.

Barringer died at the White Sulphur Springs, Greenbrier, W. Va., and was buried in Greenmount Cemetery in Baltimore. He was baptized a Lutheran, and his wife had been a member of a Quaker family, but in Raleigh they both became members of the Protestant Episcopal church. Barringer was survived by two sons, Lewin Wethered, then a young lawyer, and Daniel Moreau, Jr.