See also: North Carolina and the Lavender Scare; The Greensboro Killings on ANCHOR

The narratives of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans/Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Asexual, and people of other sexual and gender identities (LGBTQIA+) in North Carolina have a long history in the state. Some same-sex relationships and LGBTQIA+ people are documented as early as the colonial period. Different expressions of gender and relationships are also documented within Cherokee culture even earlier. Early documentation shows that living openly as a LGBTQIA+ person was classified as “misconduct” for most of the state’s history. People in same-sex relationships had to use caution due to the earliest statutes which prohibited such relationships, labeled them as "sodomy" and classified them as a crime against nature. A conviction for a "crime against nature" could result in fines, jail sentences, and worse. Until 1869, observed same-sex relationships were punishable by death in North Carolina.

About one in ten court cases of the colonial period dealt with “sexual misconduct,” which included same-sex relationships. The earliest records of LGBTQIA+ people in North Carolina can be found in colonial records. Colonial North Carolina’s stance on same-sex relationships was imported from English common law. Male-only same-sex relationships were identified as "buggery," the legal term for sodomy, under this law. One of the only court cases dealing with same-sex relationships and “buggery” in colonial North Carolina occurred in Hyde County in 1718.

John Clark was a notable resident of Hyde County. He served as a militia captain, justice of the peace, and government representative. In March 1718, Clark sued the Winn brothers, Edward and William, for slander. According to public declarations from the Winn brothers in 1716, Clark sought to “bugger” each of them, along with other “young men in the neighbourhood, as he hath done Severall times for many months past.” Clark challenged the claims in the suit, stating that their declarations had caused him “great Disgrace,” negative reception from the community, and “Trial for his Life and Danger of losing all his Estate.” When the court agreed to hear the case in July 1718, Clark did not appear and the Winn brothers were released from their charges. Clark v. Winn illustrates the culture surrounding same-sex relationships in colonial North Carolina.

Records of LGBTQIA+ people within Cherokee culture are also documented after the Revolution. In 1825, an unnamed white traveler through “Cherokee Country'' documented Cherokee men who identified as women and lived in same-sex relationships. By 1825, “Cherokee Country” consisted of southwestern North Carolina, southeastern Tennessee, northeastern Alabama and northern Georgia. "There [in the Country] were among them formerly, men who assumed the dress and performed all the duties of women and who lived their whole life in this manner." The history of same-sex (as well as gender-nonconforming) relationships and practices among the Cherokee people was first explored by ethnographer Charles C. Trowbridge. Later identifications in Cherokee society were also documented by playwright John Howard Payne in 1835.

In later publications, American Indian people (like the Cherokee) living in these relationships were identified as berdaches. Berdache was a term created by European settlers to describe gender-nonconforming or same-sex relationships. It is a term that implies a lack of consent in a relationship and a lack of morality. It was traditionally used by French settlers as a term for younger partners in male same-sex relationships. Instead, Cherokee historians and gender scholars identify people in these roles as “Two-Spirit'' people. This movement began in the early 1990s, and it sought to reconnect historians and other scholars to the culture of the Cherokee people. A two-spirit person historically held important social and family roles within Cherokee society.

English common law and its impacts on white, LGBTQIA+ North Carolinians continued after the Revolution into the early national and Antebellum periods. While records of same-sex relationships among enslaved (and free) Black people were documented across the United States, none are known to have been enslaved (or free) in North Carolina. North Carolina enacted its first crime against nature statute in 1836. It was no longer gender specific, but instead was expanded to all people in same-sex relationships. The statute deemed such acts to be a felony and were punishable by death. Many LGBTQIA+ people did not live openly during this period, due to fear of criminalization and the death penalty. In 1868, after the Civil War, the death penalty was removed from the statute. Nevertheless, same-sex relationships were still considered a crime. The punishment for being in a same-sex relationship was up to sixty years in prison.

Many court cases argued the legality and terms of LGBTQIA+ relationships from World War I until after World War II. These included North Carolina v. Savage (1912), North Carolina v. Fenner (1914), and North Carolina v. Callett (1937).

The criminalization and other punitive measures used resulted in a lack of historical references and narratives about LGBTQIA+ people in North Carolina. Documentation of LGBTQIA+ people in North Carolina and the greater United States grew significantly in the twentieth century due to the events and effects of the Lavender Scare.

The Lavender Scare became most prominent during the Red Scare in the 1950s. Gay and lesbian people working in positions within departments of the United States government began to be viewed as a new national security threat. As a result, the U.S. government terminated more than 15,000 employees based on their sexual orientation over several decades. The Lavender Scare was closely connected to North Carolina, through the involvement of prominent North Carolinians Josephus Daniels, Clyde Hoey, and James Webb. Josephus Daniels was a significant figure in the Lavender Scare due to his role in the 1919 Newport Scandal that promoted fears about gay people within the military. The Scandal was a precursor to the modern Lavender Scare. Clyde Hoey led the 1950 Hoey Committee, which investigated people in the government suspected of being gay. The Committee’s findings informed many of the actions of U.S. presidents during the Lavender Scare. Lastly, James Webb oversaw two government departments (Department of State and NASA) during the height of the Lavender Scare that fired many gay employees.

However, negative attention fostered by the Lavender Scare was not the sole public opinion. The historic Pullen Memorial Baptist Church in Raleigh, founded in the late 1800s, supported LGBTQIA+ rights as early as the 1950s during the height of the Scare. Pastor William Wallace Finlator advocated for LGBTQIA+ rights, civil rights, and women’s rights at a time when many institutions did not. Although Finlator died in 2006, the church continues to function as a progressive institution with figures like Nancy Petty, the church's first lesbian pastor.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, a significant number of LGBTQIA+ people in North Carolina began to share their sexual orientations and gender identities more openly. In the 1960s, gay clubs in North Carolina started to become more popular. Clubs with roots in the North Carolina communities of Chapel Hill and Durham were the Ponderosa, the Tempo, and the Washington Duke Hotel Bar. Gay clubs and bars were often subject to police raids and investigations. Primary sources from the 60s and 70s stated that UNC-Chapel Hill’s Wilson Library was also a popular site for gay men to meet other “like-minded” friends and seek relationships.

LGBTQIA+ authors and activists in North Carolina also published written materials openly at this time. The Feminary was a lesbian, feminist literary newsletter active from 1969-1982. The creators were graduate students at UNC Chapel Hill. They published their last issue in 1982. In its prime, “the journal published seasonally, producing poetry, personal essays, art, interviews, news, and book reviews of lesbian women in the South.”

During the 1980s and 1990s, LGBTQIA+ people in North Carolina also faced a public health threat. The AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome) epidemic had a significant impact on North Carolina's general public health, but it disproportionately affected gay men during the period. Throughout the public health epidemic, rights activists protested for better treatment. On June 28, 1981, the first LGBTQIA+ march in North Carolina took place in Durham called “Our Day Out.” The march was organized in response to the Greensboro Massacre and the anti-gay assault and murder of Ronald “Sonny” Antonevitch at Little River. Then, in 1982, activists established the first organization to provide targeted health resources for gay men living with HIV (Human Immunovirus) or AIDS. It was based in Durham and was called the Lesbian and Gay Health Project. Its goals were “to provide healthcare referrals, education, and install an AIDS support network in the Triangle...making referrals to gay-friendly physicians a top priority.” In 1985, the Lesbian and Gay Health Project established Healthline, a call-in hotline for people impacted by HIV or AIDS. The network they created was run by volunteers who provided information about health services, as well as connected people from the LGBTQIA+ community to “...organized meetings at local churches and made callers aware of gay family events, gay and lesbian sports teams, LGBT-friendly businesses, and bars." Healthline’s office was located on 9th Street in Durham. Its exact location was never disclosed in an effort to protect employees, while the key was kept in Francesca’s Dessert Caffe, formerly on Ninth Street. Healthline helped establish a stronger LGBTQIA+ community in the 80s and early 90s. The Wake County Gay and Lesbian Helpline was modeled after Lesbian and Gay Health Project’s Healthline.

Discrimination against LGBTQIA+ people evolved in the 1990s. In 1993, President Bill Clinton introduced the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT) policy. It stated military personnel did not have to disclose their sexual orientation and were protected from persecution, termination, and discrimination. However, openly LGBTQIA+ people were still not allowed to serve under DADT.

Public tone surrounding LGBTQIA+ people changed again in the 2000s. The U.S. Supreme Court decision in Lawrence v. Texas (2003) ruled that “anti-sodomy” laws were unconstitutional. Additionally, anti-hate crime legislation was later passed that criminalized violence targeting people due to sexual orientation. The North Carolina Supreme Court ruled the prohibition of same-sex relationships unconstitutional in State v. Whiteley (2005). Despite this, the North Carolina general statutes still contain the British common law language of "crime against nature, with mankind or beast." This terminology was adopted during colonial times and was used to criminalize people in same-sex relationships for decades.

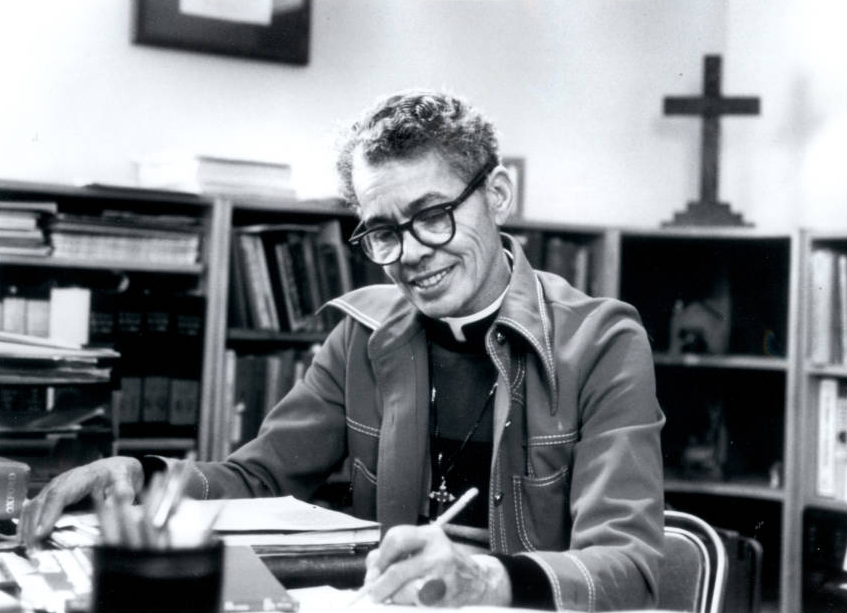

Several notable North Carolina activists advocated for liberation and equality in the Triangle. Pauli Murray, Mandy Carter, Joe Herzenberg, and Michael R. Nelson were all prominent LGBTQIA+ activists. Pauli Murray was a transgender lawyer, activist, and priest who co-authored the amicus brief legal opinion for the Supreme Court case Reed v. Reed (1971) on unconstitutional sex-based discrimination. Murray substantially impacted social justice and equity related to race, gender, and sexual orientation in North Carolina. Many of Murray’s legal findings were also used to build the landmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case that overturned “separate but equal” education. Murray wrote several books and articles about gender, race, and class. There are several murals celebrating their life and accomplishments around the Triangle. In 2012, the city of Durham established the Pauli Murray Center to illustrate their history and impact on Durham and North Carolina.

Mandy Carter, a lesbian activist, came to Durham, North Carolina from New York with a dedication to establish equality for LGBTQIA+ people. Carter co-founded Equality NC, Southerners on New Ground (SONG), and the National Black Justice Coalition. Carter notably participated in the 1990s election campaign for Harvey Gantt. Carter served “the political campaign founded by Triangle-area lesbians and gay men for the purpose of defeating [political opponent] Jesse Helms.” In 1987, Joe Herzenberg became the first openly gay council member in North Carolina when he was elected to the Chapel Hill Council. Herzenberg remained active in politics and LGBTQIA+ issues throughout his life in Chapel Hill. In 1995, Michael R. Nelson became North Carolina's first openly gay mayor, when he won election in Carrboro. He served the mayoral office for ten years.

In May 2012, voters in North Carolina approved an amendment to the state’s constitution. The amendment banned same-sex marriage. This made North Carolina the 30th state to enumerate the ban in its constitution. However, same-sex marriage was legalized in all fifty states by the Supreme Court case Obergefell v. Hodges on June 26, 2015. Partner benefits took effect after the ban was lifted across various North Carolina institutions and government entities. This included UNC Chapel Hill, NC State, Duke, Wake Forest University, the cities of Durham and Greensboro, the towns of Chapel Hill and Carrboro, and many others.

On November 20, 2019, Governor Roy Cooper signed a Proclamation for Transgender Day of Remembrance. The Transgender Day of Remembrance was started in 1999 by transgender advocate Gwendolyn Ann Smith. It began as a vigil to honor the memory of Rita Hester, a transgender woman who was murdered in 1998. It is now observed each year to acknowledge and honor the lost lives of transgender people throughout United States history.

Legal rights for LGBTQIA+ people evolved further when the landmark Supreme Court case Bostock v. Clayton County Georgia (2020) ruled for the protection of people based on their sexual orientation and gender identity. Bostock’s case was consolidated with Altitude Express v. Zarda and G. & G. R. Harris Funeral Homes Inc. v. EEOC because they were all based on Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. According to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Title VII “protects employees and job applicants from employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex and national origin. Title VII protection covers the full spectrum of employment decisions, including recruitment, selections, terminations, and other decisions concerning terms and conditions of employment.” Title VII also outlined that sex is a medical term for biological assignment male or female based on a person's genitals and chromosomes. The Court ruled that Title VII’s ban on sex discrimination also applied to LGBTQIA+ employees.

As of 2023, the month of June holds significance for LGBTQIA+ people with the legalization of same-sex marriage, the anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, and the celebration of Pride month. Pride events are held in June across North Carolina including Blue Ridge Pride Festival, Out!Raleigh Pride, and Wilmington's Hi-Wire Pride Fest and many more. Other LGBTQIA+ Pride celebrations like Alamance Pride Festival and Charlotte Black Pride Week occur in North and South Carolina throughout the year.