See also: Black Codes; Slave Patrols.

The increasing number of Black enslaved people in colonial America created suspicion and fear among the general population and led to a backlash of white reaction known as slave codes. Virginia was the first of the 13 colonies to adopt such regulations, using earlier Caribbean slave codes as models. Other colonies quickly followed suit, patterning their codes after the Virginia laws.

After the Revolutionary War, most states, especially those in the South, developed new slave codes. After the 1830s these laws became increasingly stringent, due to the tensions produced by the Nat Turner Rebellion in Southampton County, Va., and the rise of the abolitionist movement in the North. The new regulations clearly defined enslaved people as property, rather than as people, and outlawed teaching them to read and write. Enslaved people could not leave the plantation without their enslaver's permission, strike a white person even in self-defense, buy or sell goods or hire themselves out, or visit the homes of whites or free Black residents.

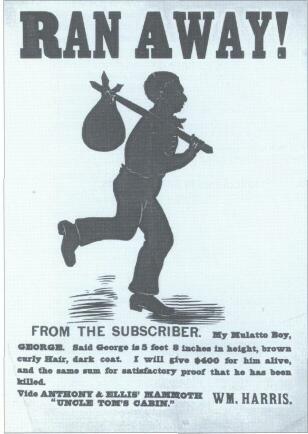

Enforcement of slave codes varied. In times of peace, enslavers gave more freedom to the people they enslaved; but in times of unrest, they rigorously enforced the slave codes both through the courts and by establishing slave patrols. Composed of white men who took turns covering a particular area of their county, slave patrols watched for runaways or assisted owners in enforcing the slave codes on their plantations.

Slave codes ended with the Civil War but were replaced by other discriminatory laws known as "black codes" during Reconstruction (1865-77). The black codes were attempts to control the newly freed African Americans by barring them from engaging in certain occupations, performing jury duty, owning firearms, voting, and other pursuits. At first, the U.S. Congress opposed black codes by enacting legislation such as the Civil Rights Acts of 1866 and 1875 and the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. But by the time of the so-called Compromise of 1877, civil rights for Black Americans had eroded, as Congress, the U.S. Supreme Court, and northerners lost interest in the issue. The slave codes essentially lived on in Jim Crow laws and other forms of discrimination until successfully challenged in the civil rights era of the 1950s and 1960s.