Slave patrols, constabulary bands of white citizens, enforced North Carolina's slave codes from the mid-eighteenth century until the end of the Civil War. A duty of all white men until the 1830s, patrolling connected nonslaveholders with the slave system, reinforcing poor whites' legal supremacy and control over blacks.

North Carolina, unlike other southern states and perhaps due to the lack of major slave rebellions, was slow to establish formal slave patrols. South Carolina first addressed the issue in 1704, ordering its militia to punish any African American caught away from home without a pass. Virginia introduced a patrol system in 1726 that restricted the guards to the apprehension of slaves. The North Carolina General Assembly did not organize patrols until 1753, although earlier laws had recognized the right of any white citizen to apprehend slaves who ran away or otherwise violated the laws of the colony. The 1753 statute required the county courts to appoint, when necessary, "three freeholders in each district as searchers" to comb slave quarters for weapons at least four times a year. Throughout the century of its existence, the slave patrol in North Carolina remained a civil organization controlled by the county courts; the state militia was called out only in periods of serious unrest.

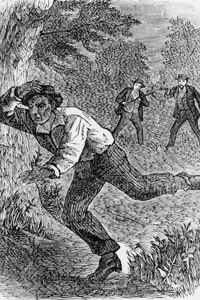

As an aspect of daily life, the slave patrol fluctuated in importance. Its primary duties were to check the passes of slaves and free blacks and break up gatherings of African Americans. In the absence of slave disturbances, patrollers sometimes neglected their duties or viewed them more as social occasions. Patrols often were ridiculed by slaves and scorned by slaveholders, who feared abuse of their chattel. Patrolling was rarely lucrative; authorities used fines, small salaries, or dismissal from other civic obligations to induce conscientious performance.

The rise of the abolitionist movement in the late 1820s stirred fears of slave insurrections across the state. In 1830 the legislature increased the maximum punishment to 39 lashes and authorized patrols to arrest anyone, white or black, caught trading with a slave. The new law also required the county courts to establish an oversight committee to appoint the patrol and hear any complaints against it.

Despite the lack of major slave uprisings in the state, Virginia's Nat Turner Rebellion in August 1831 produced criticism of the patrol system in North Carolina. In response, new laws permitted officials to call out the militia in times of hysteria caused by runaway slaves but did not allow its complete takeover of patrol duties. Nevertheless, after 1831 the patrol system lost much of its prestige. In the cases of State v. Isham Hailey (1845), State v. Caesar (a Slave) (1849), and State v. Jacob Boyce (1849), the North Carolina Supreme Court curtailed the powers of the slave patrol.

The efficacy of the state's slave patrols is unclear. Unremarkable in their daily operations and varying over place and time, the patrols provided white owners assurance, however superficial, that their chattel would not rise up against them. For blacks, the patrol served as a constant reminder of their absolute lack of freedom. After the Civil War, whites attempted to regain control of African Americans through black codes. The Ku Klux Klan's campaigns of violence and intimidation served many of the same purposes as the antebellum slave patrols.