Goodloe, Daniel Reaves

28 May 1814–18 Jan. 1902

Daniel Reaves Goodloe, abolitionist and journalist, was born in Louisburg, the son of Dr. James Kemp Strother Goodloe, a school-teacher who studied medicine but never practiced it, and Mary Reaves Jones Goodloe, the daughter of a Granville County planter, Daniel Jones. Although the Goodloes were of modest means, they traced their American ancestry to George Goodloe, who received a grant of land in Middlesex County, Va., in May 1674. Goodloe's mother died at his birth, and he was raised by his father's mother, Ann Goodloe. He attended old-field schools in Louisburg until he was seventeen, when he was apprenticed to an Oxford printer for two and a half years. He later claimed that these were the most important years of his life, when he acquired the means to style and thought through setting type. At the same time, during the furor caused by the Nat Turner Rebellion, he admitted to being prepared "to suppress imaginary combinations of insurgent negroes." In the following year, however, his lifetime course as an abolitionist was unswervingly fixed, as he read the arguments for emancipation in exchange papers from Virginia.

Daniel Reaves Goodloe, abolitionist and journalist, was born in Louisburg, the son of Dr. James Kemp Strother Goodloe, a school-teacher who studied medicine but never practiced it, and Mary Reaves Jones Goodloe, the daughter of a Granville County planter, Daniel Jones. Although the Goodloes were of modest means, they traced their American ancestry to George Goodloe, who received a grant of land in Middlesex County, Va., in May 1674. Goodloe's mother died at his birth, and he was raised by his father's mother, Ann Goodloe. He attended old-field schools in Louisburg until he was seventeen, when he was apprenticed to an Oxford printer for two and a half years. He later claimed that these were the most important years of his life, when he acquired the means to style and thought through setting type. At the same time, during the furor caused by the Nat Turner Rebellion, he admitted to being prepared "to suppress imaginary combinations of insurgent negroes." In the following year, however, his lifetime course as an abolitionist was unswervingly fixed, as he read the arguments for emancipation in exchange papers from Virginia.

For a short time after his apprenticeship, he attended the Louisburg Academy of John B. Bobbitt before moving to Maury County, Tenn., to stay with his uncle, Dabney Minor Goodloe, who sent him to school in Mount Pleasant where he was influenced by William H. Blake, a Harvard graduate. In 1836 Goodloe volunteered to fight the Native Americans, but before the Maury County Volunteers could rendezvous at Fayetteville, Tenn., the Creeks surrendered. The volunteers then agreed to serve as mounted infantry against the Seminoles in Florida. For his six months' service Goodloe was eligible for a pension, which became his primary means of support in later years. After returning to Tennessee for a short time, he went to Oxford, N.C., in 1837, where he purchased and for a year published an unprofitable weekly paper, The Examiner. Afterward he studied law under Robert B. Gilliam and received approval to practice in the county and superior courts. But Goodloe was unsuited for the law, being unable either to speak or think on his feet. Although by this time he had established himself as a promising young Whig leader, he turned aside the advice of Priestly H. Mangum, who thought politics might provide him fluency of speech and public presence. Goodloe claimed his antislavery views would leave him without a tenable defense and harm the party; altruistic and honest, the rough and ready of politics would never suit him.

Unable to find his way to fortune in either North Carolina or Tennessee, which he revisited, Goodloe set out for the nation's capital, where he arrived penniless on 22 Jan. 1844. Because of Goodloe's friendships in North Carolina, Willie P. Mangum took an interest in him and obtained him a post as associate editor of The Whig Standard. When that campaign paper suspended publication after Clay's defeat, Goodloe sought a place in the federal bureaucracy. Meanwhile, he moved on to short-term editorial associations with The Georgetown Advocate and the Christian Statesman. Then for three years he taught school in Prince Georges, Md., in order to repay loans from his benefactor, Mangum. In 1849, he returned to North Carolina for several months but decided his best possibility for employment was in Washington, where he found a post in the Tyler administration first as a clerk in the auditor's office and later in the Navy Department.

In 1841, Goodloe had begun work on a manuscript exposing the economic shortcomings of the system of slavery; his first and possibly best know essay, it was published in 1846 as a twenty-seven-page pamphlet in an edition of five hundred copies under the title, Inquiry Into the Causes Which Have Retarded the Accumulation of Wealth and Increase of Population in the Southern States; In Which the Question of Slavery is Considered in a Politico-Economical Point of View. By a Carolinian. While he was with The Whig Standard in 1844, he obtained an interview with John Quincy Adams, who read the manuscript and recommended that it be published. In March 1844 it appeared in Charles King's New York American ; it was republished in The National Era in 1847 and subsequently in other abolitionist newspapers. The pamphlet was later praised by John Stuart Mill, to whom Goodloe sent a copy in 1846. In 1849, Goodloe replied to the proslavery indictment of city life in Quaker Elwood Fisher's Lecture on the North and the South with another economic condemnation of slavery in The South and the North. During the heated debate over the admission of slavery into the territories engendered by passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, he presented additional arguments concerning the unproductivity of slavery in an 1854 pamphlet, Is It Expedient to Introduce Slavery Into Kansas? A Tract for the Times. . . . In 1855, he drafted a petition to the North Carolina legislature, entitled "Memorial of Citizens of North Carolina to the General Assembly Asking for Certain Reforms in the Laws relating to Slaves and Free Persons of Color," urging a law to recognize marriages of enslaved people, to prevent the disruption of families in enslavement, and to allow free Blacks and enslaved people to learn to read. In the midst of opposition to the Dred Scott case, he tried to show that constitutional decisions affecting popular interests should be made by the representatives of the people with a compilation of quotations from the leaders of the original Republican party of Jefferson in his Federalism Unmasked: Or the Rights of the States, the Congress, the Executive and the People, Vindicated Against the Encroachments of the Judiciary, Prompted by the Modern Apostate Democracy. Being a Compilation from the Writings and Speeches of the Leaders of the Old Jeffersonian Party. The fifteen-page pamphlet was reissued by the Republican National Convention in 1860 for circulation as a campaign document. In The Southern Platform: Or Manual of Southern Sentiment on the Subject of Slavery (1858) he made a direct appeal to the mind of Southerners by quoting the antislavery sentiments of the founding fathers from the South. The latter two compilations were typical of Goodloe's work. His prose was humdrum, even tedious, rather than impassioned, though his judiciousness was greatly admired by such newspapermen as Horace Greeley and Henry Raymond. Although his writings were relatively mild, especially in comparison to the radicalism of Hinton Rowan Helper whom he found abhorrent, they were denounced in his native state. After the appearance of The Southern Platform, Frank L. Wilson declared that Goodloe was a "God-forsaken soulless, honorless abortion of North Carolina—a thing . . . of fanaticism and hypocrisy."

He was released from his clerkship in the Navy Department when he allowed a letter approving Uncle Tom's Cabin to be published in Stowe's Key. Afterwards he began a regular connection with The National Era, a paper that had carried his works in serial form. During the summer and fall of 1853 and 1854 he relieved the ailing owner, Dr. Gamaliel Bailey, by writing the lead editorials over the signature, "G." Although his name appeared in the prospectus for 1858 as assistant editor of the abolitionist paper, by 1855 he had apparently become Bailey's assistant and the chief political writer for the Era. When Bailey died in 1859, he ran the paper until Bailey's widow was forced to close shop in March 1860. His editorials continued to emphasize the economic instability of the system of slavery. While for the most part his syntax was mild, at times he could turn harshly sarcastic; his barbs were aimed at the shortcomings of political leadership in the South as well as the stupidity of Northern politicians. His connection with the Era not only brought him in contact with Bailey and the paper's corresponding (honorable) editor, John Greenleaf Whittier, but also allowed him to become the ally and friend of America's leading writers of the time including Grace Greenwood, Mary Mapes Dodge, and Mrs. E. D. E. N. Southworth. He was particularly close to Harriet Beecher Stowe, who greatly admired his work and in 1853 proposed to carry copies of his essays with her to England.

When the Era folded, both Greeley's New York Tribune and Raymond's New York Times carried political leaders by Goodloe. As the Washington correspondent for the New York Times in 1860 and 1861, he became convinced that civil war between the North and the South was inevitable and that peace would be impossible as long as slavery existed. In Emancipation and the War. Compensation Essential to Peace and Civilization. In Which It Is Made Apparent That the Resources of the Country Are Three Fold Greater Than the Emergency, Which Will Call for Little If Any Additional Taxation, a pamphlet subsidized and published by Raymond in 1861, Goodloe recommended that the enslavers be paid for their enslaved people, believing compensation would be cheaper than an extended war.

In 1861, he received his first wartime federal appointment as clerk to the Potter Commission, charged with evaluating the loyalty of government workers, and he drafted the commission's report. Because of his pamphlet on emancipation, which attracted the attention of Abraham Lincoln, he also served on the commission appointed to establish payment for enslaved people emancipated in the District of Columbia. Goodloe held a number of other federal appointments during the war. He was offered a federal judgeship for the court of Eastern Carolina, which he refused, and it was rumored that Lincoln considered appointing him military governor of North Carolina. From 1864 to 1865 he was the associate editor of the Daily Morning Chronicle in Washington as well as a correspondent for the New York Times. From his wartime experiences he wrote two particularly important editorials, "Downfall of the Rebellion and Conciliation" (19 June 1864) and "Industrial Prospects of the South" (24 Oct. 1865) which appeared under his name. The latter article came from his work in the Department of Agriculture and that portion of the commissioner's annual report for 1865, entitled "Resources and Industrial Condition of the South," evaluating the prospects of the South for reconstruction. Before his assassination Lincoln intended to appoint Goodloe the U.S. marshal for the District of Columbia; however, the commission was not signed before the president's death.

Perhaps from a sense of guilt but even more likely because of political pressure, Andrew Johnson offered Goodloe the federal marshalship for North Carolina. Goodloe held the post from September 1865 to May 1869. In returning to North Carolina, his design was to establish a moderate, effective, and honorable Republican party by appealing to religious groups that had once favored abolition and to former Unionists who had opposed secession. His plan was doomed from the outset. He soon found himself in opposition to the president, then to the Congress, and constantly to the state's radical Republican coalition of scalawags and carpetbaggers led by William Woods Holden. Goodloe opposed Johnson's Reconstruction policies, and in 1866 he was among the Southerners who signed the call for a convention to oppose the president's programs. Although the conservatives demanded his immediate resignation because of his attendance at the National Union Convention, he cautioned the convention to moderation and with John Botts of Virginia he earnestly opposed the Black suffrage resolution. But with the passage of the Reconstruction acts, his moderation became the target of the radicals, and a growing frustration and political ineptness on his part left him in a powerless and divided minority.

In the summer of 1867 he and Hardie H. Helper obtained the shop of the Greensboro Union Register and transferred it to Raleigh, where they began issuing the Raleigh Register as an opposition paper to Holden's radical North Carolina Standard. Again in the journalistic traces, Goodloe as editor of the paper urged a moderate course of Reconstruction in the state. But he was totally alienated by the Radical Republican convention assembled in Raleigh on 4 Sept. 1867. The two opposition papers reflected the split between the two wings of the Republican party that they represented. Goodloe was particularly incensed by the referendum for the adoption of the Constitution of 1868, which he denounced as a fraud. He promptly turned over the management of the paper to Helper in order to run against Holden for governor, though he attempted to withdraw before the campaign was over; he also broke all ties with the Register over a disagreement with Helper regarding editorial policies. Goodloe detailed these events in his The Marshalship in North Carolina. Being a Reply to Charges Made by Messrs. Abott, Pool, Heaton, Deweese, Dockery, Jones, Lash and Cobb, Senators and Representatives of the State, which appeared serially in the newspapers before its publication as a pamphlet in 1869. He baldly renounced congressional Reconstruction in an 1868 pamphlet, Letter of Daniel R. Goodloe to Honorable Charles Sumner on the Situation of Affairs in North Carolina. He also published in 1868, "Shall Equality Supplant Liberty? Being a Review of Mr. Sumner's Bill and Speech." In March 1869 his enemies managed to have him turned out of office as U.S. marshal. In 1872, he supported Horace Greeley for the presidency and was elected secretary of the national executive committee for the Liberal Republicans at Cincinnati. Active in North Carolina during the campaign, he was one of the state's leaders who met Carl Schurz in Reidsville and escorted him to Greensboro.

After his final foray into North Carolina politics, Goodloe returned to Washington where he became a free-lance writer, a habitué of the Library of Congress, and for some time a Washington correspondent for the Raleigh News and Observer. In June and July 1873, he wrote a series of four letters for the Raleigh paper entitled "John Quincy Adams." In keeping with his ethic of journalistic honesty, he was one of the first writers to brave the truth about the purported Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence, publishing pieces in the Raleigh Sentinel (June-September 1873), in an extra of the New York Herald (20 May 1875) and in the Washington National Republican (20 May 1875) (drafts of the "Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence" are in his Papers). Between 1878 and 1880 he published three articles in the South Atlantic : "The Congresses Before the Constitution" (June 1878), "Finances of the Revolution" (May-June 1879), and "Emancipation in the District of Columbia" (October 1880). His "North Carolina in the Colonial Period" was published in John Hill Wheeler's Reminiscences and Memoirs of North Carolina (1884). His interest in liberal economics and sympathy with the small freeholders were sustained in A History of the Demonetization of Silver (1890) and in "Western Farm Mortgages," which appeared in The Forum (November 1890).

In 1889, Goodloe issued The Birth of the Republic: Compiled from the National and Colonial Histories and Historical Collections from the American Archives and from Memoirs, and from the Journals and Proceedings of the British Parliament, a major compilation of legislative proceedings relating to the history of the United States, published by Bedford, Clarke & Co. Earlier he had offered a twelve-page prospectus, "Synopsis of Congressional Legislation for a Century. . . . " A number of his newspaper pieces came from Birth of the Republic including "The Previous Question," published by the New York Times (22 Feb. 1891). In 1883, he registered with the Copyright Office of the Library of Congress a book to be entitled "Reconstruction of the Southern States—Being a Complete History: Embracing the plans and Experiments of Presidents Lincoln and Johnson, and the actions of the People, through their Conventions and Legislatures, under them: the reconstruction measures of Congress adopted in 1864 and the debates which led to them: the South under Military Government: the Operations of the Freedmans Bureau and of the "Ku-Klux-Klan": and the restoration of the States on the basis of Universal Negro Suffrage, and restricted White Suffrage," but he was never able to publish it. Desperate for money, he sold the rights to Samuel Sullivan "Sunset" Cox, who published it in his Three Decades of Federal Legislation. 1855 to 1885 . . . (1885) without giving credit to Goodloe, even though the section provided by him was the only worthwhile part of the book.

Starting in 1894, while he was the Washington correspondent for the News and Observer, a number of his extensive feature series were carried in the Sunday papers. The first one, "Men of Half a Century, Personal Reminiscences of Washington and Public Men for the Last Fifty Years," which began in August 1894, came from his memories of antebellum and wartime Washington (the manuscripts in letters addressed "My Dear Mary" are continued in his Papers). The second set of features dealt with events and personalities from the early history of the United States under the Constitution. But the most important series, derived from Goodloe's experiences during Reconstruction, were a severe indictment of those "knaves," who "were the founders of the Republican party as we have it now in North Carolina." The features concluded with an article on "The Trent Affair" (5 Jan. 1896). They were his last substantive work. His final publications included "Purchase of Louisiana, and how it was brought about," Southern History Association Publications (1900), and two posthumously published works, "An Omitted Chapter in North Carolina History," State Normal Magazine (February 1904), and "The North Carolina and Georgia Boundary," The North Carolina Booklet (April 1904).

Starting in 1894, while he was the Washington correspondent for the News and Observer, a number of his extensive feature series were carried in the Sunday papers. The first one, "Men of Half a Century, Personal Reminiscences of Washington and Public Men for the Last Fifty Years," which began in August 1894, came from his memories of antebellum and wartime Washington (the manuscripts in letters addressed "My Dear Mary" are continued in his Papers). The second set of features dealt with events and personalities from the early history of the United States under the Constitution. But the most important series, derived from Goodloe's experiences during Reconstruction, were a severe indictment of those "knaves," who "were the founders of the Republican party as we have it now in North Carolina." The features concluded with an article on "The Trent Affair" (5 Jan. 1896). They were his last substantive work. His final publications included "Purchase of Louisiana, and how it was brought about," Southern History Association Publications (1900), and two posthumously published works, "An Omitted Chapter in North Carolina History," State Normal Magazine (February 1904), and "The North Carolina and Georgia Boundary," The North Carolina Booklet (April 1904).

A shrewd, able journalist admired by his contemporaries, even his enemy Holden who recognized his capability as a newspaperman, Goodloe seemed incapable of managing his own affairs. Although he was a moderate abolitionist and Republican party leader with close ties to the literary abolitionists, he possessed the personal naïveté of the dogmatic and zealous reformer. Although there is no proof to the story of his intended matrimony, his biographers have felt obligated to contend with it. Supposedly, he was engaged to a Washington society belle who gave birth to a child sired by someone else without Goodloe's knowledge at the time of the marriage. The story illustrates a peculiar lack of sophistication in his makeup. It also reveals another side of his personality that made him friends of even his political enemies, because he had the marriage annulled with the full support of the bride's father, a prominent congressman. The story was known to his contemporaries and related in newspaper accounts after his death. Its acceptance, combined with his seeming disdain for material well-being and political incapacity, is as revealing of Goodloe as are his writings that successfully dealt with social and political realities.

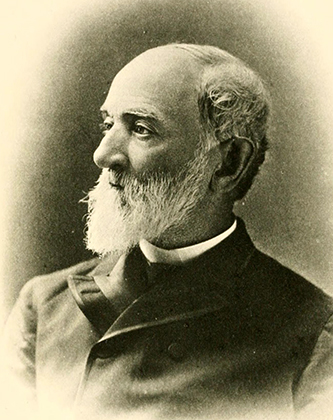

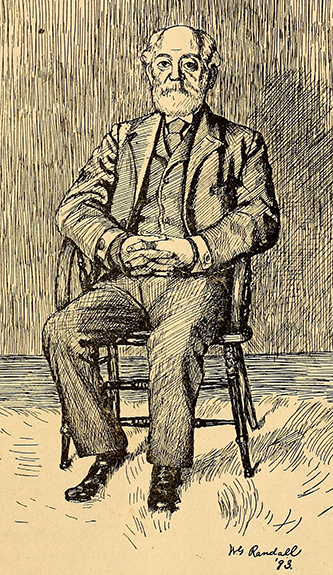

In the spring of 1896 Goodloe returned to North Carolina and four years later suffered a paralytic stroke, which left him crippled. He died in Warrenton and was buried in Fairview Cemetery. A lifelong Unitarian, he was influenced early in life by the works of William Ellery Channing. A photograph of Goodloe by Charles Parker of Washington was published in The Birth of the Republic. But his personality is better revealed in a drawing by George Randall reproduced in the North Carolina University Magazine (December 1894). Randall's portrayal shows a man of integrity and reason as well as an idealist perplexed by the harsh reality of modern politics.

References:

John Spencer Bassett, Anti-Slavery Leaders of North Carolina (1898).

DAB, vol. 7 (1931).

Douglas C. Daily, "The Elections of 1872 in North Carolina," North Carolina Historical Review 40 (1963).

Daniel Reaves Goodloe Papers (Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill).

Benjamin Sherwood Hedrick Papers (Manuscript Department, Library, Duke University, Durham).

William Woods Holden, Address on the History of Journalism in North Carolina (1881).

Edward Ingle, The Negro in the District of Columbia (1893).

Nat. Cyc. Am. Biog., vol. 10 (1909).

Raleigh News and Observer, 26 Jan. 1902.

Henry T. Shanks, ed., The Papers of Willie Person Mangum (1955).

E. D. E. N. Southworth Papers (North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh).

Joseph F. Steelman, "Daniel Reaves Goodloe.

A Perplexed Abolitionist During Reconstruction," East Carolina Collection Publications in History 2 (1965).

Harriet Beecher Stowe Papers (North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh).

Charles Leonard Van Noppen Papers (Manuscript Department, Library, Duke University, Durham).

Stephen B. Weeks, "Anti-Slavery Sentiment in the South.

with Unpublished Letters from John Stuart Mill and Mrs. Stowe," Southern History Association Publications 2 (1898).

Frank L. Wilson, Address Delivered before the Wake County Workingmen's Association (1860).

Additional Resources:

Daniel R. Goodloe Papers, 1883-1899 (collection no. 00278). The Southern Historical Collection. Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. http://www2.lib.unc.edu/mss/inv/g/Goodloe,Daniel_R.html (accessed December 4, 2013).

"Daniel R. Goodloe." The New York Times. December 8, 1900. http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=F50C13F8355515738DDDA10894DA415B808CF1D3 (accessed December 4, 2013).

MSS 099, F841, Daniel R. Goodloe letter, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library, Newark, Delaware. http://www.lib.udel.edu/ud/spec/findaids/html/mss0099_0841.html (accessed December 4, 2013).

Image Credits:

Parker, Charles. "Daniel R. Goodloe." Photograph. The birth of the republic; compiled from the national and colonial histories and historical collections, from the American archives and from memoirs, and from the journals and proceedings of the British Parliament. Chicago [Ill.]: Belford, Clarke and Co. 1889. Frontispiece. https://archive.org/stream/birthofrepublicc00good#page/n9/mode/2up (accessed December 4, 2013).

Randall, William George. "Daniel R. Goodloe, Esq." Drawing. 1893. North Carolina University Magazine 14, no. 3 (December 1894). 133. https://archive.org/stream/northcarolinauni18941895#page/132/mode/2up (accessed December 4, 2013).

1 January 1986 | Yanchisin, D. A.