Avery, Clark Moulton

3 Oct. 1819–18 June 1864

Clark Moulton Avery, Confederate officer, was the second child of Isaac Thomas and Harriet Erwin Avery of Burke County. He was graduated from The University of North Carolina in 1839 with a B.A. degree. On 23 June 1841 he married Elizabeth Tilghman Walton, daughter of Thomas and Martha McEntire Walton.

Clark Moulton Avery, Confederate officer, was the second child of Isaac Thomas and Harriet Erwin Avery of Burke County. He was graduated from The University of North Carolina in 1839 with a B.A. degree. On 23 June 1841 he married Elizabeth Tilghman Walton, daughter of Thomas and Martha McEntire Walton.

The newly married couple seemed to be in no financial want, and in 1847 Avery acquired from his father-in-law 915 acres of farm land and a brick house several miles southwest of Morganton. This house, called Magnolia, still stands.

For twenty years, Avery occupied himself with the peaceful and pleasant, though not necessarily profitable, pursuits of a slaveholding planter; and although he took an active part in local politics, he did not seek public office. He was prevailed upon by his friends to run for the proposed state convention in an election on 28 Feb. 1861 and was elected a delegate by an overwhelming majority over one of the most popular Unionists in the county. The delegates did not meet, however, because a small majority of the electors of the state voted "no convention."

Avery reacted vigorously when the institution of slavery came under attack; he became a fiery secessionist and soon was willing to maintain the righteousness of his convictions by force if necessary. On 12 Apr. 1861, hostilities began at Charleston, and on 15 Apr. Lincoln issued his "Proclamation for Coercion," calling on all states to furnish troops to fight to preserve the Union. For North Carolina, this was the last straw, and on 17 Apr. Governor John W. Ellis issued his rejoinder, calling the General Assembly into special session on 1 May; on the same date, the companies of the First Regiment of the North Carolina troops volunteered and by 16 May were formed into a regiment at the state capitol by order of the adjutant general. They called themselves the First North Carolina Volunteers and signed up to serve six months. Company G, the Burke Rifles, was one of the ten companies of this regiment, and Captain Clark Moulton Avery was the company commander. Colonel Daniel Harvey Hill was regimental commander. The entire regiment reached Richmond by 21 May and after camping there for several days, on 24 May moved by rail and steamboat to Yorktown on the peninsula between the York and the James rivers. On 10 June, Colonel Hill's troops, with several Virginia companies, were attacked by a Union force of about 4,400 men at Big Bethel Church. In this small battle the Federal forces were defeated and driven from the field within a few hours. Wrote D. H. Hill in his official report: "Captain Avery Company G displayed great coolness, judgment and efficiency in the battle of Bethel." After that time this regiment was known as "The Bethel Regiment." While the regiment was still at Yorktown, an order received from the adjutant general of North Carolina changed its designation from the First to the Nineteenth Regiment; the officers held a  meeting and adopted resolutions opposing the change in a most vehement manner. On 12 Nov. 1861, the regiment was mustered out of service in Richmond; it returned to North Carolina the following day and disbanded. Appointed lieutenant colonel of the Thirty-third Regiment of North Carolina troops, which was in the process of organizing and training at the old fairground in Raleigh (later at Camp Mangum), Avery was promoted to colonel as of 17 Jan. 1862.

meeting and adopted resolutions opposing the change in a most vehement manner. On 12 Nov. 1861, the regiment was mustered out of service in Richmond; it returned to North Carolina the following day and disbanded. Appointed lieutenant colonel of the Thirty-third Regiment of North Carolina troops, which was in the process of organizing and training at the old fairground in Raleigh (later at Camp Mangum), Avery was promoted to colonel as of 17 Jan. 1862.

He instituted a rigorous training program for his regiment, and their later brilliant record is evidence of the value of such training.

In an action near New Bern, Avery was captured when the Thirty-third and Twenty-sixth North Carolina regiments, after making a valiant stand, were surrounded and overrun by the enemy. He was transported to Old Fort Columbus on Governor's Island, N.Y., and moved to Johnson's Island, Ohio, during the summer of 1862. Here, although the housing conditions were very crowded, the prisoners were furnished sufficient food to keep them from starving. After seven months' imprisonment, Avery was released by exchange. His health had been undermined by the imprisonment, but he would take only a short leave from his troops before returning; he returned to active duty in the late fall of 1862. In December, his regiment played a vital role at the Battle of Fredricksburg in closing the gap between the troops of generals James H. Lane and James J. Archer. Avery received his first disabling wound of the war at the Battle of the Orange Plank Road in May 1863. Soon returning to his troops, he was again wounded at Gettysburg.

After a short time with his family, Avery was again leading his forces at the Battle of the Wilderness, where they were under attack by Grant's troops. He was struck in the right thigh by a bullet and later, while lying on a litter, was again hit in the body and neck, and his left arm was shattered by a minié ball. His left arm was amputated, and he was moved to the Orange County Courthouse, where he was nursed by the women of the community; six weeks later he died from an infection in the leg wound.

A daughter, Laura Pairo, was born to Colonel and Mrs. Avery on 27 May 1864, shortly after he was fatally wounded; she was named for the woman who nursed Avery until his death. He was first buried in Virginia, but his wife, a short while later, took a servant and rode on horseback to Virginia to return his body to Morganton for permanent burial. They both lie now in the church yard of the First Presbyterian Church, Morganton.

Avery was survived by four children: Martha Matilda, who married George Phifer; Harriet Eloise, who married the Reverend James Colton; Isaac Thomas; and Laura Pairo, who married the Reverend John A. Gilmer.

This person enslaved and owned other people. Many Black and African people, their descendants, and some others were enslaved in the United States until the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery in 1865. It was common for wealthy landowners, entrepreneurs, politicians, institutions, and others to enslave people and use enslaved labor during this period. To read more about the enslavement and transportation of African people to North Carolina, visit https://aahc.nc.gov/programs/africa-carolina-0. To read more about slavery and its history in North Carolina, visit https://www.ncpedia.org/slavery. - Government and Heritage Library, 2023

References:

Samuel A. Ashe, ed., Biographical History of North Carolina, vol. 7 (1908).

Isaac Thomas Avery, personal recollections.

Elroy McKendree Avery and Catharine Hitchcock (Tilden) Avery, The Groton Avery Clan, vol. 1 (1912).

Edward W. Phifer, "Saga of a Burke County Family," North Carolina Historical Review 39 (1962).

John H. Wheeler, Historical Sketches of North Carolina (1851).

Additional Resources:

Documenting the American South, UNC Libraries: https://docsouth.unc.edu/global/getBio.html?type=bio&id=pn0000061&name=Avery,%20Clark%20Moulton

Avery Family of North Carolina Papers, 1777-1890, 1906 (collection no. 033). The Southern Historical Collection. Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. http://www.lib.unc.edu/mss/inv/a/Avery_Family_of_North_Carolina.html (accessed February 8, 2013).

The Avery Museum: #

Ashe, Samuel A. (Samuel A'Court). Biographical history of North Carolina from colonial times to the present. Greensboro, N.C. : C. L. Van Noppen. 1905. https://archive.org/details/cu31924092215494 (accessed February 8, 2013).

Search results for Clark Mounton Avery in the North Carolina Digital Collections.

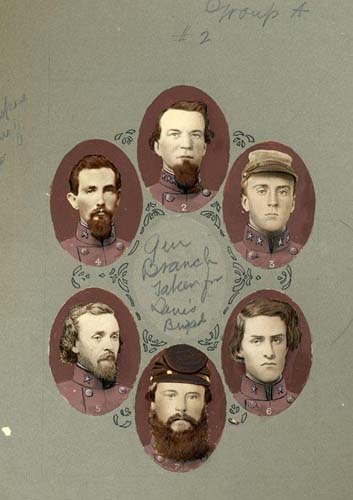

Image Credits:

Clarke Moulton Avery, from the UNC General Alumni Association. Available from http://alumni.unc.edu/veterans/veteran.asp?pid=706694084 (accessed February 8, 2013).

"Photograph, Accession #: H.19XX.332.155." 1900-1910. North Carolina Museum of History.

1 January 1979 | Avery, Isaac Thomas, Jr.