Currency

Part i: Diverse Currency and Severe Money Shortages in Colonial North Carolina; Part ii: Revolution-Era Currency and the Importance of North Carolina Gold Production; Part iii: The Civil War and the Nationalization of the Monetary System

Part III: The Civil War and the Nationalization of the Monetary System

By 1860 there were 36 banks in North Carolina, issuing many millions of dollars in bank notes. Nearly all of the currency by the 1850s was being printed for the banks by engraving firms in New York and Philadelphia. These currencies were far more elaborate in design than earlier varieties. Their detailed images and overlays of color challenged even the most skillful counterfeiters.

By 1860 there were 36 banks in North Carolina, issuing many millions of dollars in bank notes. Nearly all of the currency by the 1850s was being printed for the banks by engraving firms in New York and Philadelphia. These currencies were far more elaborate in design than earlier varieties. Their detailed images and overlays of color challenged even the most skillful counterfeiters.

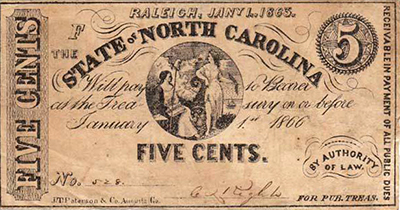

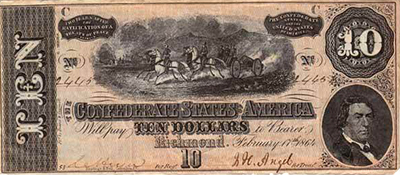

North Carolina joined the Confederacy in 1861, and the Confederate Constitution, like its federal counterpart, reserved the coining of money for the South's central government. It did not, however, specifically restrict the states from producing money in other forms. Since the Confederacy's national government lacked adequate metal reserves to produce coinage, it was forced to rely on paper currency to finance the war against the North. Authorities in each of the Confederate states also printed their own notes. As a result, the South's overall monetary system included a wide assortment of paper currencies.

Between 1861 and 1865, North Carolina authorized the printing of over $16 million in treasury notes. This amount was  small when compared to the monstrous sums issued by the Confederate government, but for North Carolina it proved to be too much. The strains of war made it impossible for the state's currency to hold its value. In the closing months of the Civil War, runaway inflation and the advancing Union armies led to the frantic production and distribution of southern currency. Clothing and basic foodstuffs by then were commanding huge prices, and gold or other personal valuables, not paper money, were required to buy them. By early 1865, a North Carolinian needed as much as $600 to buy a pair of shoes and $1,500 to purchase an overcoat.

small when compared to the monstrous sums issued by the Confederate government, but for North Carolina it proved to be too much. The strains of war made it impossible for the state's currency to hold its value. In the closing months of the Civil War, runaway inflation and the advancing Union armies led to the frantic production and distribution of southern currency. Clothing and basic foodstuffs by then were commanding huge prices, and gold or other personal valuables, not paper money, were required to buy them. By early 1865, a North Carolinian needed as much as $600 to buy a pair of shoes and $1,500 to purchase an overcoat.

The federal financing of the Civil War led to the nationalization of all U.S. currency. In 1863 the United States began issuing national bank notes. These notes were printed by the authority of the federal government, but they were issued through private banks in the North and, after the war, throughout the entire country. Thousands of private banks were eventually granted national banking charters and were allowed to issue bank notes. In 1865, soon after the fall of the Confederacy, the National Bank of Charlotte became the first of 147 banks in North Carolina that received such a charter.

Since 1887 all U.S. paper currency has been made by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing in Washington, D.C. In an effort to further centralize the nation's monetary system, the U.S. government in 1913 established the Federal Reserve System. This system continues to be the means by which the flow of U.S. currency is controlled, credit is regulated, and cash is introduced into the economy. The paper currencies now used in the United States are Federal Reserve notes. North Carolina is located in the Fifth Federal Reserve District, an area served financially by the Federal Reserve Bank in Richmond, Va.

References:

Grover C. Criswell, Douglas B. Ball, and Hugh Shull, Comprehensive Catalog of Confederate Paper Money (1996).

John J. McCusker, Money and Exchange in Europe and America, 1600-1775: A Handbook (1978).

Mattie Erma Edwards Parker, Money Problems of Early Tar Heels (1957).

Alan D. Watson, Money and Monetary Problems in Early North Carolina (1980).

Additional Resources:

Fulghum, R. Neil. "A Brief History of North Carolina Money." Historic Moneys in the North Carolina Collection. North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill University Libraries. http://www.lib.unc.edu/dc/money/ncmoney.html (accessed October 1, 2012).

"Historic Moneys in the North Carolina Collection." North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill University Libraries. http://www.lib.unc.edu/dc/money/index.html (accessed October 2, 2012).

Fulghum, R. Neil. "Hugh Walker and North Carolina's 'Smallpox Currency' of 1779." The Colonial Newsletter. December 2005. p.2895-2920. http://www.lib.unc.edu/dc/money/1779article.pdf (accessed October 3, 2012).

Image Credits:

J. T. Paterson & Company. "Currency, Accession #: S.HS.2008.59.4." 1863. North Carolina Historic Sites.

Evams & Cogswell. "Currency, Accession #: S.1980.159.9" 1864. North Carolina Historic Sites

1 October 2012 | Detreville, John R.; Fulghum, R. Neil; Norris, David A.; Paden, John; Towles, Louis P.