Segregation in the 1920s

"Assigned Places"

by Flora Hatley Wadelington; Revised by SLNC Government and Heritage Library, June 2023

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian. Spring 2004.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

See also: Civil Rights Movement; Civil Rights in North Carolina; Public Education; Private Education; School Desegregation

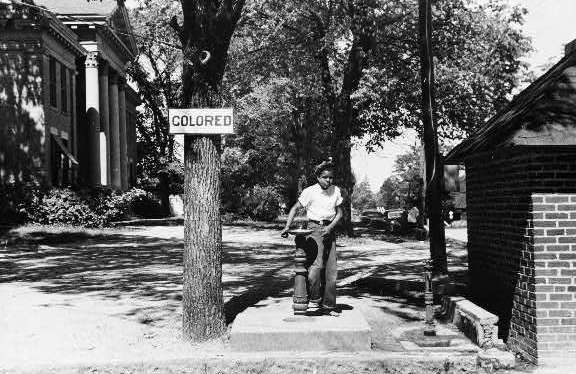

When one thinks of the past, many images come to mind. One of the most prominent images of the early twentieth century in the South was the COLORED and WHITE signs that dotted the landscape across the South. Those signs were the visible images that constantly reminded African Americans of their place in a white society. In storefront windows, waiting rooms, and public accommodation facilities, segregation signs appeared.

When one thinks of the past, many images come to mind. One of the most prominent images of the early twentieth century in the South was the COLORED and WHITE signs that dotted the landscape across the South. Those signs were the visible images that constantly reminded African Americans of their place in a white society. In storefront windows, waiting rooms, and public accommodation facilities, segregation signs appeared.

Segregation, or racial separation, was carried out by the legislature of southern states enacting laws. The earliest laws legalized segregation in trains and other public conveyances where Black and white people mingled. Eventually a complex web of statutes created a color line that separated the races. These statutes came to be known as Jim Crow laws.

The term Jim Crow denotes a policy of segregation and originated in a song of the same name sung in minstrel shows. North Carolina enacted segregation laws that mandated the separation of citizens by race or color. As those segregation laws became entrenched, so did social customs and practices that accompanied Jim Crow.

One of the areas where the image of segregation was most visible in North Carolina in the 1920s was in education. The General Assembly had appropriated funds to support a statewide system of public education in 1907. With such funding, the State Department of Public Instruction began to build schools on a segregated basis. In 1907 the state authorized the establishment of secondary schools for whites in rural areas. By 1911 approximately two hundred rural schools had been established in ninety-three of the state’s one hundred counties.

Public elementary schools for African Americans were built in 1910, and in 1918 the first public secondary school for African Americans was established. Most such high schools were limited to only one or two years. Between 1923 and 1929, public high schools for African Americans were built in larger counties such as Mecklenburg, Durham, Forsyth, Guilford, and Wake. Second Ward High School in Charlotte opened in 1923, and students traveled from every direction to attend.

The task of supervising the segregated public schools for African Americans fell to the Division of Negro Education, created in 1921 as part of the State Department of Public Instruction. The parent-teacher organization was also segregated. The North Carolina Congress of Colored Parents and Teachers became the first African American parent-teacher association in the state. Annie Wealthy Holland founded the organization in 1928.

However, segregation was not limited to separating Black, white, and American Indian children in North Carolina’s public schools. Segregation extended to restaurants, travel, amusement and recreation facilities, libraries, hospitals, prisons, housing, and municipal services such as fire stations. Restaurants did not seat people of color in the dining room, and movie theaters had balcony seating for African Americans. There were separate libraries and hospitals, or white hospitals had a separate ward where African American patients were treated. Lincoln Hospital in Durham was considered the most modern hospital for African Americans when it was rebuilt in 1925.

However, segregation was not limited to separating Black, white, and American Indian children in North Carolina’s public schools. Segregation extended to restaurants, travel, amusement and recreation facilities, libraries, hospitals, prisons, housing, and municipal services such as fire stations. Restaurants did not seat people of color in the dining room, and movie theaters had balcony seating for African Americans. There were separate libraries and hospitals, or white hospitals had a separate ward where African American patients were treated. Lincoln Hospital in Durham was considered the most modern hospital for African Americans when it was rebuilt in 1925.

With the enactment of segregation laws, customs and practices evolved that became part of the Jim Crow system. Although these customs and practices existed, they were not actual laws that the legislature passed. African Americans had to adhere to rigid customs and practices in their daily contact with whites. It was the custom for African Americans to always address whites as Mister, Miss, and Ma’am, while whites called African Americans by their first names or simply Sister and Boy, regardless of their ages. Another custom was for African Americans patronizing white shops and stores to enter through the back door and wait until white patrons were helped. Segregation laws, customs, and practices led some African Americans to establish businesses, restaurants, funeral homes, and stores that served the African American community. By the 1920s Durham had a thriving African American business district made up of North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company and Mechanics and Farmers Bank, which provided financing for numerous additional Black businesses that opened during the decade.

North Carolina, like most southern states in the 1920s, was rigidly segregated. Jim Crow was a system designed to let African Americans know their place and to keep them in it. Relegated to second-class citizenship, African Americans across the state, from cities and towns to rural areas, endured a system of segregation while building their own institutions.

At the time of this article’s publication, Flora Hatley Wadelington was a professor of history at Saint Augustine’s College in Raleigh and has coauthored the book A History of African Americans in North Carolina.

Educational Resources:

Grade 8: Moments in the Lives of Engaged Citizens who Fought Jim Crow. North Carolina Civic Education Consortium. http://civics.sites.unc.edu/files/2012/05/MomentsintheLivesofEngagedCiti...

Image Credit:

Drinking fountain on the county courthouse lawn, Halifax, North Carolina . Photograph created by John Vachon. Image courtesy of Library of Congress. Available from http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/fsa1997003218/PP/ (accessed December 20, 2012).

A cafe near the tobacco market, Durham, North Carolina. Photograph created by Jack Delano. Image courtesy of Library of Congress. Available from http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3c29840/ (accessed December 20, 2012).

1 January 2004 | Hatley Wadelington, Flora