Born in Wilmington, N.C. in 1785, to a free mother and an enslaved father, David Walker, although deemed free by law, was no stranger to the “avaricious” (a term he uses throughout the Appeal to characterize many in the South). In 1827, he migrated to Boston and married a freedom-seeking enslaved person , supporting his family by selling second-hand clothes. Walker spent ample time studying the global history of slavery, was a leader in his community, and eventually published a speech in the first African-American news journal printed in the United States, Freedom’s Journal, in 1828. Increasingly outspoken in his denunciation of slavery, David Walker published three editions of his Appeals between 1829 and 1830. He died in 1830, presumably of tuberculosis (the same disease that claimed the life of his daughter only a few weeks before), though the abruptness of his death led some to claim that he was poisoned.

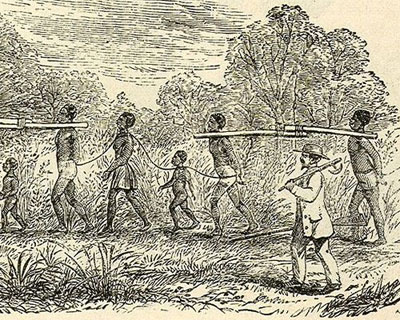

Walker’s passionate and heartfelt Appeal is a call for rebellion, but it also examines what he saw as some of the root causes of the profound “wretchedness” which characterized every African-American, especially those who were enslaved. He first surveys the history of enslavement, contrasting the “heathen” practices of Greece, Rome, Egypt, etc.--in which enslaved people were certainly cruelly mistreated, but in which some enslaved people could free themselves and even rise to prominence within the society--with the practices of slavery in Christian America, which sought to dehumanize enslaved people and characterize them as mere beasts of burden. He next surveys the legislated ban on educational opportunities for both enslaved and free people of color, suggesting that the forbidden access to Christian morals promoted brute behavior, and the lack of formal education blighted the opportunity for self growth or ennoblement.

Walker next examines social and political agencies through which enslaved people were further subjugated. Even as the invocation of God provided solace and hope to the enslaved, He was also invoked by white clergymen—no less products of the zeitgeist than the openly racist enslavers—who used the Bible to justify slavery, and condemned enslaved people for disobeying their masters. Finally, Walker excoriates plans to re-colonize free black people in Africa as an attempt not to rectify the suffering of an oppressed minority, but instead as a way to remove even the few exemplars of black social mobility who existed.

Smuggling them into North Carolina via New York or Boston coastal vessels, distributors of the Appeal particularly sought to spread the call to action throughout the cities of the coastal region, such as Wilmington, Fayetteville, and Elizabeth City. So successful were these smuggling efforts that Wilmington Magistrate of Police, James F. Mcree, felt compelled to communicate with Governor Owen, warning him of a pamphlet “exaggerating [the blacks’] sufferings, magnifying their physical strength and underrating the power of the whites; containing also an open appeal to their natural love of liberty; and throughout expressing sentiments totally subversive of all subordination in our slaves….”

The publication of Walker’s Appeal soon transformed the thinking and actions of blacks and whites alike. The Appeal increased southern white paranoia about the potential for an uprising of enslaved people against their enslavers, and was an impetus for increased restrictions on both free and enslaved Black people. Nonetheless, the document became a catalyst for Nat Turner’s Insurrection in Southampton County, Virginia, leading in turn to even more restrictive actions.

Perhaps because of the Appeal’s particular emphasis on God and the Christian Bible, black preachers became particular objects of suspicion. In Washington, for instance, blacks were forbidden to congregate except to attend white preaching services, and laws were introduced after the Nat Turner revolt to forbid blacks to preach at all. Calvin Jones, editor of the Raleigh Star, notified Governor Stokes of an “incendiary” preacher who attempted to influence enslaved people in Chapel Hill and Hillsborough to revolt. Jones suggested prohibiting the sale of liquor to blacks, forbidding the assembly of black people at “musters, elections, and other places where they acquired insolence and audacity, and prohibiting the learning to read and write.” Newspapers around the state reported portrayed black preachers as “the greatest villains,” and vilified them as instigators of uprisings in various locations.

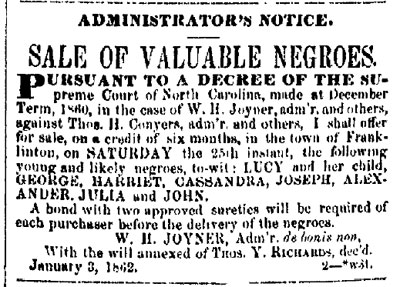

During the 1830 legislative session almost one-third of the public acts passed by legislature pertained to blacks. To prevent the dissemination of the Appeal, black people

were pilloried, whipped, and imprisoned for one year for a first offence. On a second offence, the person was killed without benefit of clergy. Anyone aiding a freedom -seeking enslaved person was fined $100, and soon thereafter it became illegal to teach an enslaved person to read or write, and forbidden to give a slave any literature.

Laws were also passed making it more difficult to attain freedom, and increased restrictions on free blacks (who could, presumably, taint the minds of enslaved people). Laws limited the movement of free blacks, prohibited re-entry after being absent from the state for ninety days, and enjoined free black citizens from communicating with other free blacks on incoming ships. Further restrictions included the prohibition of marriage between free and enslaved black people, as well as between blacks and whites. The quarantine act of 1830 prevented any free person of color or free black person from entering into the state.

Additional laws, passed after Nat Turner’s Revolt, further reduced those few liberties black people, free and enslaved alike, had enjoyed. Laws incorporating militia companies—called out to assist in the suppression of riot and rebellion—increased from sixteen between 1830 and 1831 to twenty-three from 1832-1833. Other laws were passed to speed up the trial of slaves involved in any capital offense, and to prevent enslaved people from hiring their own time and keeping house as free persons, and in 1835, an amendment to the 1776 NC Constitution revoked the voting rights of free people of color.

Despite these efforts, Walker’s words continued to resonate. David Walker’s Appeal posits a black nationalist ideology, focusing on liberation, self-liberation, and self-improvement among both free and enslaved black people, while unapologetically iterating a call for revolt and the vengeance of God. The Appeal aroused fear and paranoia among the South’s white citizens, leading to numerous and increasingly draconian restrictions on the lives and interactions of enslaved and free black people. Nonetheless, his words promoted increased pride and understanding that, once in the hands of succeeding generations, would begin the process of emancipation.