See also: Lighthouses; Lightships; Cape Hatteras Lighthouse (from UNC-CH); Oak Island Lighthouse; Old Baldy Lighthouse; The Roanoke River Lighthouse; Lighthouses Map

Lighthouse facts

- Number of steps: 214

- Height to focal plane of lens: 158 feet above sea level

- Height to top of roof: 162 feet

- Number of bricks: approximately one million

- Thickness of wall at base: 5 feet 8 inches

- Thickness of wall at parapet: 3 feet

- Position: 34 miles south of the Cape Henry (Virginia) Lighthouse 32 1/2 miles north-northwest of Bodie Island Lighthouse

- Coast Survey Chart: 36° 22'36" N latitude, 75° 49'51" W longitude.

- Distance from which light can be seen: 18 nautical miles

History

As it had reported in previous years, in 1872, the U.S. Lighthouse Board (which later became a part of the U.S. Coast Guard) stated that ships, cargoes and lives continued to be lost along 40 miles of dark coastline that lay beyond the reaches of existing lighthouses on North Carolina’s coasts. Southbound ships sailing closer to shore to avoid the Gulf Stream were especially in danger. In response, work began on the Currituck Beach Lighthouse in 1873 with completion two years later.

On December 1, 1875 the beacon of the Currituck Beach Lighthouse filled the remaining "dark space" on the North Carolina coast between the Cape Henry light to the north and Bodie Island to the south. The Currituck Beach Lighthouse was the last major brick lighthouse built on the Outer Banks. To distinguish it from other regional lighthouses, its exterior was left unpainted and gives today's visitor a sense of the multitude of bricks used to form the structure.

The lighthouse is known as a first order lighthouse, which means it has the largest of seven Fresnel lens sizes. The original source of light was an oil-lamp consisting of five concentric wicks, the largest of which was 4 inches in diameter. A mechanical means was required to rotate the huge lenses that made the light appear to flash. A system of weights suspended from a cable powered a clockwork mechanism beneath the lantern--much like the workings of a grandfather clock. The lighthouse was electrified in the 1930s and the 20-second flash cycle (3 seconds on and 17 seconds off) used at that time continues to warn ships hugging the chain of barrier islands along the coast. The beacon comes on automatically every evening at dusk and can be seen for 18 nautical miles. The distinctive sequence enables the lighthouse not only to warn mariners but also to help identify their locations.

The Lighthouse Keepers' House, a Victorian "stick style" dwelling, was constructed from pre-cut and labeled materials which were shipped by the U.S. Lighthouse Board on a barge and then assembled on site. In 1876, when the Keepers' House was completed, two keepers and their families shared the duplex in the isolated seaside setting.

In the five decades that the lighthouse burned oil, twenty-one men served as keepers. Until 1921, the lighthouse had one principal keeper and two assistants serving at a time. After 1921, the principal keeper had only one assistant. They carried fuel up the tower, cleaned the lenses, trimmed the wicks, and wound the clockwork mechanism that rotated the lens (every 2.5 hours). The penalty for allowing the light to go out was dismissal. Along with their wives and children, keepers raised livestock, kept a garden and maintained the buildings and grounds.

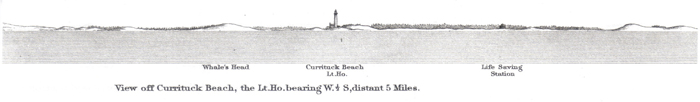

When the Station was built, little of the greenery that shades the site today existed; the dwelling, the outbuildings and the tower (on top of a deep and solid foundation) were built on sand and had views of the Atlantic Ocean and the Currituck Sound. The Atlantic Local Coast Pilot from 1885 reports that the coast “presents… an almost unbroken beach of hard white sand, with frequent ranges and clusters of sand hills, varying in height from ten to eighty feet, backed here and there by scattered clumps of trees and occasional patches of wood…” (The image below accompanied that description).

The initial flash pattern for the lighthouse was one of 5 seconds of red light interrupting a stream of white light every 85 seconds. The lens had three flash panels on it (“bulls-eyes”) and the carriage on which they sat would have made a full rotation every 4.5 minutes. As shipping sped up, so did the need to quickly identify landmarks. By 1918 the lighthouse had a more efficient lamp (an incandescent oil vapor lamp installed in 1913) as well as a flash pattern that had more than doubled in speed – 1.5 seconds of red every 45 seconds. In 1933 the lighthouse was electrified and when in the late 1930s it was automated the keepers were no longer needed. The Station became uninhabited.

By the late 1970s, the Lighthouse Keepers' House stood open to the elements with no windows or doors; porches had decayed and vines invaded the north side. Much of the interior millwork had been vandalized. Concerned about the preservation of the historic property, Outer Banks Conservationists, Inc. (OBC), a private non-profit organization dedicated to the conservation of the character of the Outer Banks of North Carolina, signed a lease with the State of North Carolina in 1980 to begin a phased restoration of the property. The lease charged the group with the responsibility of restoring the Keepers' House and improving the historic compound.

The grounds and walkways were rejuvenated and the exterior of the Keepers' House was nearly complete as of 2011, although the interior was still undergoing restoration.

OBC worked with the N.C. Department of Cultural Resources (NCDCR) to restore the smaller dwelling on the north side of the complex. This house was built for the lighthouse keeper of Long Point Light Station (and later also depot) in the Currituck Sound in 1881. In 1920 that station, which serviced the Sound’s lights, was transferred off Long Point Island to Coinjock, NC. The house was placed on a barge and moved to the Currituck Beach Light Station as a residence for one of the keepers and his family.

Other historic structures located within the Currituck Beach Lighthouse compound include an outhouse and a storage building. The two-hole privy has been repaired and the storage building with its four sharp finials has been restored and now serves as the lighthouse staff office. Two cisterns which store rainwater may be seen flanking the Keepers' House.

In 2010, OBC worked with NCDCR and the state’s underwater archeologists to salvage a shipwreck that had become uncovered on the beach. The wreck, now thought to be from the early 1600s and the oldest shipwreck found in North Carolina, spent time near the lighthouse before being moved to the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum in Hatteras.