Culpeper's Rebellion in 1677-78 was the most significant of the many rebellions and coups of the Proprietary period in Albemarle County. A variety of problems led to the unrest in the colony that finally resulted in the overthrow of the provincial government. The Albemarle colony was a geographically isolated backwater frontier settlement that fostered self-government and individual initiative. Showing greater interest in their economically more promising colony of Charles Towne (now Charleston, S.C.) in southern Carolina, the Lords Proprietors paid little heed to the growing problems in Albemarle. By the mid-1670s the colony's government was on shaky ground from long-term internal power struggles, an uncertain land policy, rumors that the Proprietors might relinquish the colony to Governor Sir William Berkeley of Virginia, the institution of the more structured semifeudal Fundamental Constitutions, and the lack of commissioned officials. The economy was dealt a severe blow by the Plantation Duty Act of 1673, which imposed a burdensome duty on tobacco to ensure its export to England. If enforced, this duty would curtail the New England intercoastal traders, who were willing to brave the treacherous waters of North Carolina. Another factor that may have inspired the upheaval was that some of the rebels fled into Albemarle after Bacon's Rebellion in Virginia in 1676.

The last commissioned governor of Albemarle, Peter Carteret, left for England in 1672 to air the colony's grievances with the Lords Proprietors, appointing John Jenkins to be president of the council (acting governor). As the years passed with no relief and the commissions of Jenkins and the council ran out, there was increasing discontent in the colony among the political opposition. Jenkins was briefly deposed by Thomas Eastchurch and then returned to power. Eastchurch, appealing to the Proprietors, was commissioned governor in 1676. On the return voyage he tarried in the West Indies to court a new wife, sending his assistant Thomas Miller on to Albemarle as the deputy governor. Although Eastchurch had no legal authority to make this appointment, Miller was initially accepted by most of the colony's settlers on his arrival in July 1677. Miller's political enemies increased, however, when he began collecting the customs duties, seizing cargoes and ships, and making arbitrary arrests.

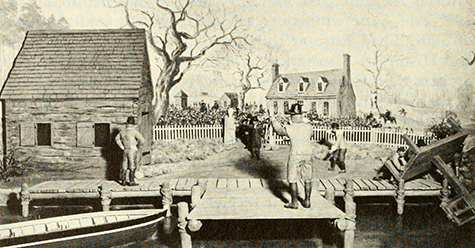

On 1 Dec. 1677 Miller arrested a popular New England trader named Zachariah Gillam, who had brought arms in his ship, and George Durant, a key leader in the opposition faction. By 3 December John Culpeper, who had earlier been involved in unrest in Charles Towne, had organized armed parties to release Gillam and Durant, arrest Miller and council member John Nixon, and seize the county records and seal. Culpeper's "Remonstrance" became the call for revolt throughout the colony, and the deputy customs collectors, Henry Hudson and Timothy Biggs, also were captured. At a rebel assembly on 24-25 December, Miller was to be tried, but a proclamation condemning the revolt from Governor Eastchurch, who had arrived in Virginia, broke up the meeting. Miller and Biggs were committed to a temporary prison. A rebel council with Jenkins as the acting president took over the government, and John Culpeper was elected customs collector. Eastchurch's untimely death ended the threat to suppress the rebellion from Virginia.

Early in 1678 Biggs escaped to England and was rewarded by the Lords Proprietors with appointment as comptroller of customs. To bring order to the colony, the Proprietors named one of their own, Seth Sothel, as governor. On the voyage to the colony, however, Sothel was captured and held for ransom by North African pirates. John Harvey, a respected planter of Albemarle, was appointed governor, receiving his commission in the summer of 1679. When Miller escaped to England, his account led to the arrest and trial for treason of Culpeper, who also had gone to England to explain his actions to the Proprietors. To circumvent the voiding of their charter, the Proprietors chose to defend Culpeper and were able to achieve an acquittal. This trial apparently is the reason the rebellion bears his name.