During the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, while clock makers in New England and the mid-Atlantic hand-crafted brass clock movements for tall case and other clocks, few North Carolinians made clocks because the state had not developed cities large enough to support the trade. Thomas Emond, a clock maker known to have worked in Raleigh from 1806 to around 1820, signed an eight-day tall case clock he created for William Boylan. Johann Ludwig Eberhardt (1758-1839), who moved to the Moravian town of Salem in 1799, made more than 30 tall case and shelf clocks, some of which are in the collection of Old Salem, Inc. Other Moravians made clocks, though not on this scale.

The pioneering work of Eli Terry of Connecticut during the first two decades of the nineteenth century led to the mass production of wooden clock movements-first for tall case clocks and later for shelf clocks. Demand for inexpensive shelf clocks manufactured by Terry, Seth Thomas, and other Connecticut makers resulted in the demise of the tall case clock and the widespread practice of clock peddling. The North Carolina General Assembly enacted legislation in 1822 that required those who wished to peddle clocks and other products not manufactured in the state to obtain a license annually from a county sheriff, paying a tax of $20 on each wagon or cart used to transport goods. This legislation, with some modifications, remained in effect at least until October 1858.

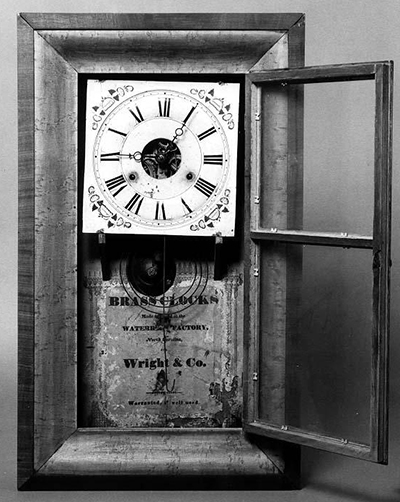

Enterprising manufacturers, dealers, and peddlers tried to circumvent the legislation in various ways. Some obtained clocks manufactured in Connecticut (often by Thomas) and pasted their own printed labels inside the cases, while others pasted over the manufacturer's name on the original labels with the name of a fictitious manufacturer in North Carolina. A few wily entrepreneurs in the state may have established assembly shops for clock components manufactured in Connecticut. Early examples with wooden movements, and later examples with brass movements, include North Carolina clocks "made" by J. R. McElever, Oliver & Co., Reeves & Huson, Reeves, Saunders & Co., H. Wright & Co., and Wright & McKee. Such clocks are owned by the North Carolina Museum of History and the North Carolina Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

During the late nineteenth century, several North Carolinians obtained clock-related patents. On 11 May 1875, George W. White and Walter I. Leary of Edenton obtained one for an "improvement in clock-escapements." Four years later, Robert S. Abernethy, a mathematics professor at Rutherford College and a resident of Happy Home in Burke County, obtained a patent for another improvement in escapements.