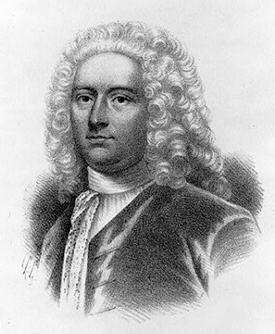

February 1611–August 1674

Sir John Yeamans, Proprietary governor of Carolina and landgrave, was born in Bristol, England, where he was baptized at St. Mary Redcliffe on 28 Feb. 1611, the son of John, a Bristol brewer, and Blanche Germain Yeamans. He married a Miss Limp, who probably was the mother of his five sons, William, Robert, George, Edward, and one whose name is unknown, and three daughters, Frances, Willoughby, and Anne. He migrated to Barbados by 1638 and formed a partnership for land acquisition with Benjamin Berringer by 1641. In 1643 Yeamans and Berringer were living on the same plantation in St. Peter Parish, but after 1648 the partnership was dissolved.

Yeamans accumulated wealth as a successful planter and gained political prominence in the colony's assembly, on the council, and as a judge in the courts of common pleas. He acquired the confidence of John Colleton, a former royalist officer turned planter and politician. With the restoration of Charles II, Colleton successfully developed the concept, which appears to have been his idea initially, for the establishment of the Proprietary colony of Carolina. As the principal spokesman for the eight Lords Proprietors of Carolina, Colleton took the lead in trying to attract settlers to that colony.

Prior to his intense involvement in the settlement of Carolina, Yeamans married, on 11 Apr. 1661 Margaret Foster, the daughter of the Reverend John Foster and the widow of Yeamans's former business partner, Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin Berringer. The Berringers were the parents of Mary, Simon, John, and Margaret, who was born after the death of her father. Evidence has been uncovered that the last years of the Berringer marriage were unhappy, that Margaret had transferred her affection to John Yeamans, and that the Berringers were virtually separated. Berringer died in January 1661 after a prolonged and undetermined illness. Suspicion was raised at the time, admittedly by Yeamans's political enemies, that Yeamans and Margaret Berringer had conspired to murder her husband. Yeamans was cleared of these accusations by the council of Barbados, and the Berringer estate passed to Margaret Yeamans and her children. For a time the Yeamanses lived on Nicholas Plantation (now St. Nicholas Abbey), built by Benjamin Berringer after 1656 and considered one of the three great Jacobean houses surviving in the Western Hemisphere.

The attention of the first prospective Carolina settlers focused on the Lower Cape Fear region, which the Proprietors named the County of Clarendon. Here a colony sponsored by the Corporation of Barbadian Adventurers from Barbados and elsewhere established itself in 1664. The Lords Proprietors, however, soon shifted their interest to a more southerly site near Port Royal. Taking advantage of this interest, another group of Barbadians, led by Yeamans, Sir Thomas Modyford, and Peter Colleton, negotiated through Yeamans's son Major William Yeamans a Proprietary endorsement for a colony at Port Royal. As a mark of their favor and to add to Yeamans's prestige, the Proprietors prevailed on King Charles to confer upon him the honor of knight baronet on 12 Jan. 1665. On the preceding day the Proprietors had appointed him "Governor of our County of Clarendon neare Cape Faire and of all that tract of ground which lyeth southerly as farr as the river St. Mathias."

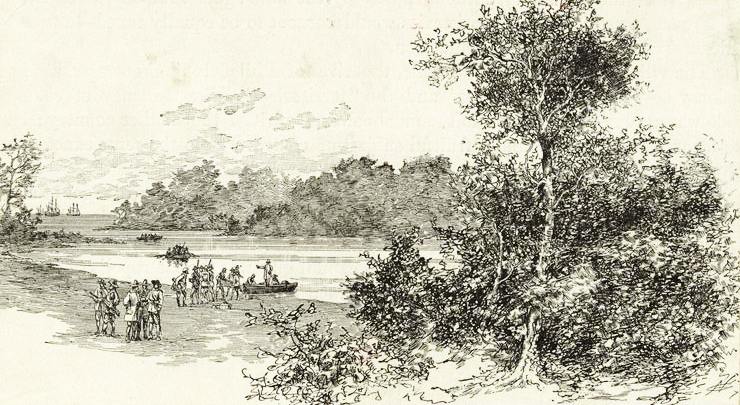

In October 1665 Yeamans sailed from Barbados for the Cape Fear with three ships planning to explore southward from there to Port Royal, where he hoped to found a colony. As Yeamans's fleet attempted to enter the Cape Fear River, his largest vessel ran aground and sank. Though most of the passengers were saved, his supplies were lost, including the cannon with which he intended to fortify the Port Royal settlement. Shortly after this Yeamans sent another of his vessels to Virginia to obtain food, clothing, and other supplies for the Clarendon settlers, only to have it wreck on the return voyage.

Yeamans remained on the Cape Fear from early November until shortly after Christmas. Here the governor made plans for Robert Sandford, secretary of the colony, to undertake an exploratory voyage to the south, which was later successfully carried out. Having presided over a meeting of the General Assembly of Clarendon, the governor boarded his one remaining vessel and sailed for Barbados never again to return. For another year and a half the Clarendon settlement hung on, but by the close of the summer of 1667 the last of its settlers departed, and Clarendon County ceased to exist. Its governor meanwhile was embroiled in the uncertain and often tempestuous politics of Barbados and seems to have made no effort to save his colony.

Under the vigorous leadership of Lord Ashley, soon to be created Earl of Shaftesbury, the Proprietors in 1669 renewed their efforts to settle Carolina and dispatched a fleet of three ships with colonists aboard bound for the Port Royal area. With the fleet went a blank commission as governor and commander-in-chief addressed to Sir John Yeamans, at Barbados, who was instructed to fill in the document with his own name or that of another of his choice. Yeamans took command of the expedition, hired the sloop Three Brothers to replace a vessel that had sunk off Barbados, and sailed for Carolina. A great storm scattered the fleet, and the two surviving ships sought safety in Bermuda. Here Yeamans decided, for reasons that are unclear, to withdraw from the expedition and to return to Barbados. He then appointed William Sayle, a septuagenarian and a former governor of Bermuda who had had some earlier connection with Carolina, to take his place as governor.

The expedition then proceeded to Carolina where it established a colony not at Port Royal, but at Albemarle Point on the Ashley River. This colony became the nucleus of South Carolina. Yeamans finally reached the colony in the summer of 1671 with his wife, some of his children, and about fifty immigrants from Barbados in his party. The Proprietors on 5 Apr. 1671 had bestowed upon him the title of landgrave. This was the highest rank in the colony's nobility created by the Proprietors under their new framework of government known as the Fundamental Constitutions. Yeamans expected to be immediately acclaimed as governor of the colony, for under the provisions of the Fundamental Constitutions when a Proprietor was not present in Carolina, the highest ranking member of the native nobility would become governor. Joseph West, who had been named governor following the death of William Sayle, refused to give up his office until he received orders from the Proprietors.

Meanwhile, Yeamans established a plantation on Wappoo Creek and reportedly introduced slavery to the colony. Despite repeated efforts to gain the governorship, he was stymied until the Proprietors, acting in accordance with the provisions of the Fundamental Constitutions, ordered that the landgrave be given preference to a commoner and sent him a commission.

On 26 Mar. 1672 the Council proclaimed Sir John governor. In an effort to provide needed food supplies for the colony in 1672 and 1673, Yeamans made liberal use of the Proprietors' credit without their approval. It was also charged in the colony that he had attempted to make huge profits from the food shortages and that his actions had helped bring on these shortages. Displeased at last with Sir John after years of the closest association, the Proprietors on 25 Apr. 1674 revoked his commission as governor and proceeded to appoint Joseph West as his successor. Before this news reached the colony, however, Governor Yeamans died, and on 13 Aug. 1674 Joseph West was named to succeed him.

Lady Margaret remained in South Carolina for several years securing additional land grants that she left to her daughter Margaret, who later became the wife of Colonel James Moore, the founder of a second and permanent settlement on the Cape Fear. Lady Margaret eventually married Captain William Walley and returned to Barbados, where she died.

Sir John Yeamans continues to be an enigmatic figure. He clearly deserves credit as a founder of the two Charles Townes—first on the Cape Fear and then in southern Carolina—but his terms as governor of each of the colonies were more controversial. Circumstances conspired to overwhelm the fledgling Cape Fear colony, but Yeamans initially tried to save the settlement. His interest, however, lay farther south. His tenure in the southern colony was marred by dissension, although again he attempted, even beyond Proprietary limits, to meet the colony's most pressing problems. The accusation that he alienated his friend's wife and then murdered him cannot be absolutely proven, but the circumstantial possibility seriously compromises his character. Seen in the best light, Yeamans may be viewed as an energetic and restless adventurer who was actively involved in the West Indian colonization of the mainland, playing a significant role in the founding of the Carolinas.