27 Dec. 1821–26 Oct. 1901

Josiah Turner, Jr., Confederate congressman, editor, and opponent of Reconstruction, was born in Hillsborough, the eldest son of Josiah and Eliza Evans Turner. The father, a longtime sheriff and large landowner in Orange County, sent his son to the Caldwell Institute at Greensboro and then for a year to The University of North Carolina. After two years of legal study in Hillsborough, Josiah, Jr., was admitted to the bar in about 1845. He soon built up a large practice, based partly on his father's influence and partly on his own sharp wit and tongue. In 1856 he married Sophie Devereux, of Raleigh, who bore him four sons and a daughter.

Turner's political career opened with his election to the state House of Commons as a Whig in 1852. He was reelected in 1854, defeated for the state senate in 1856, then elected senator in 1858 and 1860. Turner was ardent to the point of excess in every cause he took up. This included his opposition to secession; but once the decision was made, he raised a company of cavalry for the Confederate service and became its captain. Severely wounded in April 1862, he was disabled from further service and subsequently resigned his commission. In 1863 he was elected to the Confederate Congress as a peace candidate and opponent of the Davis administration. He delivered as promised, opposing conscription, impressment, taxation, and the suspension of habeas corpus so outspokenly as to be assigned to the "lunatic fringe" of that congress. In November 1865, as an old opponent of secession, he was elected to the Federal Congress but, in company with the others chosen at that time, was denied his seat. In 1866 and 1867 he was appointed a director of the state-owned North Carolina Railroad, and in 1867 he was elected its president.

At the end of the war Turner set himself resolutely against all but the most minimal divergence from the old order. Never one to do things by halves, he became the most caustic and uncompromising enemy of congressional Reconstruction when it made its appearance in 1867. Late the next year, with funds borrowed from industrialist George W. Swepson, Turner bought the Raleigh Sentinel and made it the leading Conservative newspaper in the state. Here lay his major lifework, flaying the Republican administration of Governor William W. Holden with loosely substantiated charges of fraud and dictatorship, ridiculing its supporters for their real or imaginary foibles, often with outrageously clever nicknames, and lending encouragement to every Conservative opposition device including the Ku Klux Klan. (Holden's rival Raleigh Standard referred to Turner as King of the Ku Klux, but there is no evidence that he was ever more than an apologist for the order.) Turner was a master of polemical journalism at a time when that style was in high fashion. Other papers took their lead from the Sentinel when they did not quote it directly, and he thereby contributed as much as anyone in the state to the overthrow of Governor Holden in 1870. This was all the more pleasant for Turner, as he had been briefly imprisoned by the governor's militia earlier that year owing to the blunder of one of its commanding officers.

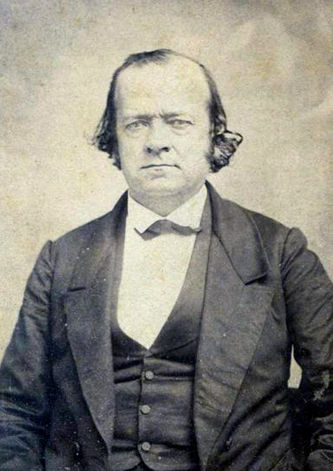

But Turner's victory proved his undoing. Erratic and even destructive by temperament, he belonged congenitally to the opposition. Fellow Conservatives mistrusted him and he turned against them. He declined a congressional nomination in 1872, apparently expecting a U.S. senatorship that did not materialize, and the congressional nomination was denied him two years later. As a delegate to the Conservative-oriented constitutional convention of 1875, he outdid his fellows in denouncing past Republican measures. A year later he sold his newspaper, still encumbered with debt despite its previous popularity and large circulation. He was defeated in a bid for the state senate in 1876, endorsed by the Republicans, then ran unsuccessfully for Congress as an independent in 1878. He was elected to the lower house of the legislature in 1878, however, only to be expelled for disorderly ad hominem attacks upon his colleagues. After another failed congressional race in 1884, Turner flirted with populism in the 1890s and ended his life a Republican. An Episcopalian, he died at his home in Hillsborough, where he was buried in the churchyard of St. Matthew's Church. The North Carolina Collection in Chapel Hill has a portrait of him.