16 Dec. 1802–31 Dec. 1835

William Swaim, newspaper proprietor and editor, was born in the Centre community of Guilford County, the son of Marmaduke and Sarah Fanning (Fannon) Swaim. His father was a large landowner, and William, the oldest boy in the family, worked on the farm until he was twenty.

As a youth he was known for his bright mind, shrewd remarks, and keen sense of humor, but he was twelve before he learned to write. Previously he had attended an old field school for two months and had learned to read well enough to understand the few books available to him. William asked his father, who wrote a bold and plain hand, to make examples for him to copy. Thereafter, while neighborhood boys wandered aimlessly about on Sundays, young Swaim would settle down in some undisturbed place, as he wrote in his diary, to a "laborious day's writing."

His father occasionally took him to Greensboro, and when court was in session he listened intently to the lawyers as they represented clients or talked among themselves. In 1819 he determined to become a lawyer himself and from then on spent every free moment in reading books borrowed from a Quaker neighbor, Nathan Dick. His first selection was Sir Richard Blackmore's Creation, a long poem based on the intellectual philosophy of John Locke. The organization of a circulating library in the community gave Swaim access to a greater variety of books—philosophy, history, poetry, law, and medicine—which served his desire "to learn about all subjects."

When he was eighteen he enrolled for a two-month term in a local school. He only attended when the weather was unsuitable for farm work, however, as he felt that his labor was necessary to help support the family's eight children. His interest in learning led to his appointment as a teacher in a newly organized Sabbath School at Bethlehem Church. Based on his work there, he was appointed superintendent of a Sunday school at Mount Ephrim schoolhouse. When his cousin Benjamin Swaim was engaged to teach a day school in the same building, William became his assistant. Declining to accept pay for this work, he asked that instead three of his siblings be permitted to attend the school.

The Mount Ephrim school experience marked a turning point in William Swaim's life. Benjamin, five years older than he, was well educated and owned a good library. He set about to help William with his studies. Together they organized a debating club, the Polemic Society, and men of all ages participated in its programs. Leading questions of the day were debated, and the society became a strong educational influence in William's life.

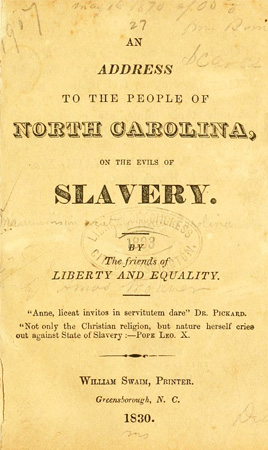

As the young man began to take part in discussions on slavery, education for all citizens, constitutional reform, and other social questions, he put aside his wish to become a lawyer and instead determined to make printing his profession. In 1824 he joined the Manumission Society of North Carolina and shortly afterwards was made its secretary, a post he filled for six years. During this time he became acquainted with Benjamin Lundy, author of The Genius of Universal Emancipation. In March 1828 Swaim went to Baltimore to study the "mysteries of practical printing" under Lundy's direction. Swaim reviewed the publications that came into Lundy's office, visited the city library, listened to conversations in his boardinghouse, observed happenings on the streets, and began to write for publication. Lundy was impressed and in less than two months made Swaim his assistant editor.

Six months later Swaim's father died, and his mother called him home to take charge of the family's affairs. While acting as his father's administrator, William was in the office of The Patriot and Greensborough Palladium when the editor, T. Early Strange, proposed that Swaim buy the paper and printing establishment. With only six months of schooling, Swaim pondered with deep concern the move from plowboy to proprietor and editor of a newspaper. After discussing the possibility with intelligent and trustworthy friends, he signed the contract on 11 Mar. 1829 and took over the Greensboro newspaper and printing establishment.

On 4 April he published a "Prospectus" for his forthcoming newspaper, the Greensborough Patriot, announcing its purpose: "To spread before the public a faithful account of all the events and transactions, both foreign and domestic, that may agitate the political world—to scrutinize closely the conduct of men in power, and chastize their misdoings without regard to rank—to pull the mask from the face of corruption and hold up popular vices to view in their 'native deformity'—to break the spell, which has long palsied the energies of the Southern States, and show them the necessity of improving their advantages—and to influence our young countrymen, with warm hearts and 'lips of fire,' to 'plead their Country's cause'—shall constitute the prominent objects of the GREENSBOROUGH PATRIOT."

The first issue of Swaim's paper appeared on 23 May 1829, when, in an "Address to Our Patrons," he presented the topics he intended to keep before the public. Among them were education, scientific agriculture, sound banking and currency, social justice, clean politics, and freedom of the press—policies seen by leading men of the state as necessary to lift North Carolina out of its long period of decline.

Although Swaim considered himself to be a political independent, the paper leaned towards the Whigs (following the Civil War, long after Swaim's death, it became Democratic). His editorials were fearless in their attacks, sparkling with wit and humor or burning with sarcasm, and always in a language that could not be misunderstood. Widely read, the paper was later described by Stephen B. Weeks as "a leader of the best thought in its day."

The front page of the first issue also supported the cause of constitutional reform in North Carolina. Representation in state government had become one-sided, with eastern counties tightly holding control. In a subsequent issue Swaim predicted that constitutional revision would come "by peaceful means if possible, by revolution if necessary." At a convention in June and July 1835 the long-anticipated changes were made—a mere five months before Swaim's death from an earlier, undescribed accident in Fayetteville. He was buried in the First Presbyterian Church cemetery, Greensboro.

On 29 Apr. 1830 Swaim married Abiah Shirley of Princess Anne County, Va. In 1832 their only child, Mary Jane Virginia, was born. She married Algernon Sidney Porter, and their son was William Sydney Porter (O. Henry).