10 Oct. 1897–21 Jan. 1959

Lamar Stringfield, composer, conductor, and flutist, was born near Raleigh, the son of the Reverend Oliver Larkin and Ellie Beckwith Stringfield. He was the sixth of seven children. In 1902 the family moved to western North Carolina, and as a lad Lamar grew up among the mountains, which he came to love and which later had a significant influence on his musical career. His father served short terms as pastor of churches in Barnardsville, Burnsville, and Asheville before establishing a permanent home for the family in Mars Hill, where a son and a daughter were already employed as teachers at Mars Hill College. Lamar, with his family, joined the Baptist church in that community.

As was true of all the Stringfield children, Lamar received his early education at home, taught by his mother and his older sisters. He was enrolled for three semesters in the academy program at Mars Hill College, but his attendance was irregular and the college seems to have had a very limited effect on his intellectual development. Far more important was the influence of a family in which study and music were a natural part of each day's activities. His oldest sister gave him his first formal music lessons when he was six. Within a few years he had not only acquired a good foundation in the piano but had also begun to experiment with other instruments, especially the cornet. While the family lived for a few months at the Baptist Assembly in Ridgecrest, he became interested in the banjo. Day after day he "picked" with local people as they sat around the railway station and heard some of the folk tunes that would inspire compositions of his own. It is probable that he first learned the ballad of John Henry from railroad workers in Ridgecrest.

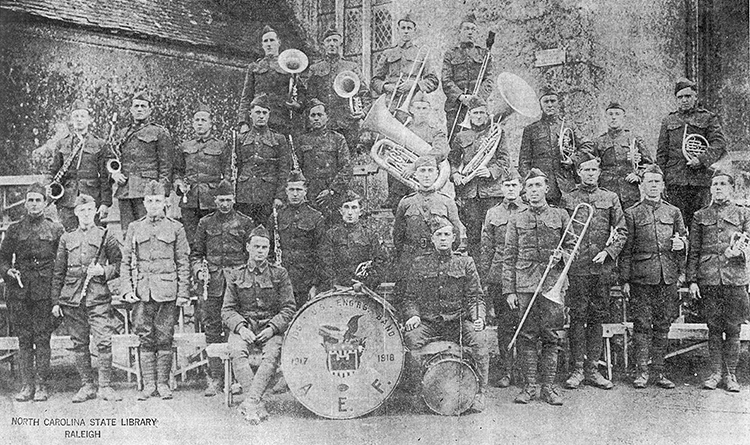

World War I interrupted his sporadic studies at Mars Hill College and opened an exciting career in music. In 1916 he joined the army, serving first on the Mexican border and then in France as a member of the band with the 105th Engineers, 30th Division. The band members, who doubled as litter bearers, were assigned to the medical corps and given the task of bringing the wounded from front-line positions to first-aid stations before they were sent on to hospitals. The group also served in Belgium and finally on the Hindenburg Line.

When Stringfield joined the army, he was playing the cornet, but he soon discarded that instrument for the flute and began taking lessons with Harold Clark, a member of the Tennessee contingent from Knoxville. At the same time he began to study music theory with the bandmaster, Joseph DeNardo. From the beginning Lamar showed considerable promise as a flutist, and after the armistice was signed and the band pulled back for reorganization, he was selected as one of five men to study in Paris with some of the best instructors in France.

Discharged from the army in April 1919, Stringfield returned home to devote his life to music. He resumed his studies in theory with DeNardo, who had moved to Asheville, and enrolled for flute lessons with Emil Medicus, another teacher in Asheville. During this time he also began composing in earnest. In 1919 he wrote "Lost" for piano, and the next year he composed "In Lindy's Cabin" for violin and piano, "Polka Dot Polka" for cornet, and three other short pieces.

In 1920 he decided to move to New York, where he would have better opportunities for study and for performing. Entering the Institute of Musical Art (later the Julliard School of Music), he studied flute with George Barrere, composition with Percy Goetschius, Franklin Robinson, and George Wedge, and conducting with Chalmers Clifton and Henry Hadley. As a student he won his first cash prize for his "Indian Legend," a symphonic poem based on folk materials and Cherokee Indian themes. Another of his student compositions, "Mountain Sketches" (1923), written for flute, violoncello, and piano, was first performed at the institute. In 1924 he was graduated with an artist's diploma in flute playing.

Stringfield remained in New York, conducting and performing as a flutist. He served as guest director for the Baltimore Symphony, the New York Civic Orchestra, the Philadelphia Civic Orchestra, and some fifteen other organizations. As a flutist he played for two seasons with the Chamber Music Art Society and for three seasons with the New York Chamber Music Society. During the 1927–28 season he served as one of the conductors of the National Opera Association in Washington, D.C. For his orchestral playing and conducting he was awarded a certificate by the American Orchestral Society. Meanwhile, this was one of his most productive periods in composing. In 1928 his "From the Southern Mountains" won the Pulitzer Prize for Composition.

The year 1928 was pivotal in Stringfield's life. Not only did it bring him one of the highest awards for composing, but it was also the year in which he turned from a concentration in music making to an emphasis on establishing musical organizations and on implementing private financial plans. In 1930 he returned to North Carolina, where he spent the rest of his life, except for short summer tours as a lecturer at the Julliard School of Music and one summer at Claremont College in California. Establishing his residence in Chapel Hill, he immediately began to sell his ideas for a program in folk music to the Department of Music at The University of North Carolina. The outcome was the creation of the Institute of Folk Music, with Stringfield as its research associate. It was the institute's purpose, as he saw it, to utilize old folk tunes in such a way as to preserve them for future generations. Out of its work and its concerts came the idea for organizing a state symphony orchestra. During the summer of 1927 Stringfield had already set up and directed the Asheville Symphony Society.

The North Carolina Symphony Society was formed in March 1932, and through its efforts a symphony orchestra was established. On 7 Apr. 1934 Stringfield left the Institute of Folk Music in order to devote full time as director of the new orchestra. No substantial funds had been committed to the project, but on 4 May the Federal Relief Administration of North Carolina granted $45,000 for its support for a period of thirty-six weeks. During the summer and fall the orchestra gave seventeen concerts throughout the state, and the foundation was laid for a good musical organization. Statewide acceptance of the project was demonstrated when, after federal funds were no longer available and it became evident that the orchestra could not sustain itself, the North Carolina legislature appropriated funds for its support and thus created the first state-supported symphony orchestra in the United States.

Meanwhile, in October 1935 Stringfield was appointed regional director of the Federal Music Project under the Works Progress Administration and found it necessary to give up his work with the symphony. His new assignment was to promote the establishment of a number of orchestras in seven southern states, using the North Carolina plan as a model. The idea of amateur orchestras greatly appealed to Stringfield, and he set himself the tasks of organizing a Southern Symphony Orchestra and of establishing a Society of American Symphony Orchestras to sponsor a system of orchestras nationwide. As he envisioned it, the Southern Symphony would provide concerts for more than four million people who lived in small towns or rural areas and had little or no opportunity to hear good musicians perform. It also would encourage young musicians and provide a vehicle for the presentation of American compositions. Stringfield visited major cities in the South and conferred with many groups, but he did not succeed in selling his plans for a Southern Symphony. Though the Society of American Symphony Orchestras was organized in July 1940, his plans for both a Southern Symphony and a national network of orchestras were given up when the United States entered World War II in December 1941.

The period after 1935 was less productive for Stringfield than earlier years. His work with the Federal Music Project consumed much of his time without providing compensatory satisfaction in the fulfillment of his cherished dreams, and marital difficulties added to the disappointments experienced in his work. He and his wife, Caroline Crawford, whom he had married on 1 May 1927, were divorced in July 1938; they had one child, Meredith. Afterwards Stringfield returned to New York as associate conductor at Radio City Music Hall for one season, but his earlier creativity seems to have escaped him. World War II added one more dimension to his personal frustrations.

When the United States entered the war, Stringfield became so emotionally involved that he had little time for music. Rejected by the armed forces because of age, he sought other means by which he could contribute to the war effort. For this reason the musician undertook research on the feasibility of using overtones in the treatment of shell-shock patients and of piping music into clubs and dining halls for the mental relaxation of service members. Although interested, the Federal Security Agency was unwilling, or unable, to invest any money in the project. His second effort on behalf of the nation was more fruitful. In October 1942 he took a job with the Vaught-Sikorsky Aircraft Corporation and spent two years working in an airplane factory, first on the assembly line and then as inspector of engines.

After the war Stringfield became involved in a variety of musical projects, among them the writing of music for a number of outdoor dramas (in 1937 he had composed the music for Paul Green's play, The Lost Colony ). In the late forties he worked with LeGette Blythe on his Shout Freedom, a play commissioned by the Mecklenburg Historical Society, and in 1952 he wrote the music for Hubert Hayes's Thunderland, which ran for two seasons in Asheville. He also resumed his interest in conducting, and during the 1946–47 season, he commuted from Asheville to Knoxville, Tenn., to serve as conductor of the city's symphony orchestra. He turned down a three-year contract with that orchestra because of the stipulation that he establish permanent residence in Knoxville and accepted a position with the Charlotte Symphony instead. In January 1947 Stringfield was asked to serve on the National Board of Directors of the National Society of Music and Art, and in April he was elected regional consultant of the National Association for American Composers and Conductors. In December 1949 he accepted a commission to write the music for Peace, a Christmas contata based on a poem by Marian Sims. The composition was first presented at the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church in Washington, D.C., on 18 December.

Two other projects engaged Stringfield during the forties and fifties. For several years he had wished to make a more nearly perfect flute. After studying acoustics with a physics professor at Case Institute of Technology in California and then working with casting and making molds, he set up a woodwind repair shop in Charlotte and set about constructing his new, improved flute. He modeled the flute after one made by Louis Lot in Paris about eighty years earlier, using white gold for the tubing and springs. He also patented an invention that eliminated the use of screws to hold the pads in the key cups. A Stringfield Design Flute was built, but the detailed work necessary to duplicate his model made it unattractive to commercial producers. His second project, that of establishing a business to prepare plates for engraving music and of teaching the art of engraving to his most talented students, also failed and left him heavily in debt.

The financial failure of these projects was only one of several disappointments marring Stringfield's last years. In 1951 he began work on his last major composition, a musical folk drama called Carolina Charcoal. He spent four years on it, hoping for a good reception on Broadway and then success in Hollywood. Neither goal was realized. The play premiered at the Barter Theater in Abingdon, Va., and ran for three showings in Charlotte, but he found no backers in New York and Hollywood turned him down. His efforts to make "Daniel Boone," a song from Thunderland, a best-seller and a financial asset also failed. His performing honorariums helped with expenses, but he was plagued by debts. Attempts to secure a teaching position, first at Mars Hill College and then with the state school system, did not succeed because he had neither a traditional college degree nor the professional training needed to teach. Faced with financial disaster, he tried to keep a full recital schedule but repeated illness made that difficult.

As his health deteriorated during the fifties, Stringfield returned to Asheville to be near his family. Attacks of sinusitis, repeated operations for a hernia condition, a broken leg, and other physical problems, as well as extreme sensitivity to the effects of alcohol, left him a broken man. At age sixty-two he died in the hospital of lung congestion. He was buried in Riverside Cemetery, Asheville.

Stringfield left some 400 compositions, 150 published and about 250 unpublished. Most of his larger works were for symphony orchestra and chamber music, but his collection also included an opera, integral music for stage plays and radio, and smaller pieces for voice and instrumentals. Most of his compositions and other materials are at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.